Bawdy Technologies and the Birth of Ectoplasm

[1] By the late nineteenth century, Spiritualism, a religious movement that promised communication with the dead through spirit mediums, had attracted a broad range of prominent followers like the American suffragist Victoria Woodhull, the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, and the beloved creator of Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle. Although the Spiritualist movement did not offer any formalized religious belief beyond its commerce with spirits, its protean nature would come to accommodate very elastic physical evidence of life beyond the grave. Such material demonstrations would also offer female mediums a unique form of agency that reached beyond the political ends and religious goals of the Spiritualist séance room. On or about 1894, communications from the spirit world changed with the emergence of ectoplasm, a term invented by Nobel laureate and French physiologist Charles Richet. It was an often glutinous substance that emerged from various parts of the medium’s body. At times, these globulous, wandering projections were purported to tip tables. Serpentine ropes of the stuff would emerge from the medium’s ear to rest in fat coils on her shoulder and embryonic limbs and heads would drop like otherworldly stillbirths from the medium’s genitals. According to British physicist and psychical researcher Oliver Lodge, Richet’s encounters with ectoplasm led him to affirm: “C’est absolument absurd, mais c’est vrai!” [It’s absolutely absurd, but it’s true] (364).

[2] Absurd though it appeared, ectoplasm seemed to redefine the boundaries of the next great scientific frontier. Dr. Gustave Geley, a French physician and psychical researcher, viewed this paranormal production as evidence of an evolutionary development of human organic capacities and believed that this development heralded a revolution in scientific thought. The physical attributes of ectoplasm seemed to vary as much as those who produced it. According to psychical researcher G. C. Barnard, Geley described ectoplasm as being “very variable in appearance, being sometimes vaporous, sometimes a plastic paste, sometimes a bundle of fine threads, or a membrane with swellings or fringes, or a fine fabric-like tissue” (88). It was sometimes incandescent and sometimes opaque. The color of the material varied but was usually white. Geley believed that the material was “capable of both evolution and involution, and is thus a living substance” but noted that it was unlikely that it ever separated from the medium’s body (88).

[3] In one of his many books on spiritualism and paranormal phenomena, The Edge of the Unknown (1930), Conan Doyle described ectoplasm as “a viscous, gelatinous substance which appeared to differ from every known form of matter in that it could solidify and be used for material purposes” (216). He also noted that “this substance was actually touched by some enterprising investigators, who reported that it was elastic and appeared to be sensitive, as though it was really an organic extrusion from the medium’s body” (216). Ectoplasmic extrusions appeared to behave like the eyes of a snail, retracting when touched and reemerging when unmolested. Ectoplasm also shared a special physical relationship with the medium who produced it, though this relationship would also vary among mediums. Doyle suggested that ectoplasm often functioned as a more sensitive body part, noting that if it was “seized or pinched […] the medium cried aloud” (216). That such observers would seize and pinch this physical extrusion reveals not only the intimate nature of the contact between mediums and psychical researchers, but also the punitive measures such researchers were willing to take in grasping their subjects.

[4] Ectoplasm emerged at a time when women’s bodies were under special scrutiny: surgical gynecology allowed physicians to examine pathological conditions hidden within the female body and medical practitioners had devised and made use of gynecological instruments like the speculum that could reveal female interiors. It was also during this period that parts of the female anatomy were being removed through procedures like the ovariotomy, a surgery designed to treat phantom ailments like nymphomania and hysteria. In view of such procedures and in spite of the active exploration of the female anatomy, female physiology and behavior remained inscrutable. Even Sigmund Freud, equipped as he was with an arsenal of analytical implements, could not by 1926 penetrate what he called the “dark continent” of female sexuality. It is unsurprising, then, that male psychical researchers of the period regarded ectoplasm, a palpable—and often gynecological—externalization of the spirit world, as a substance that promised to revolutionize the scientific one.

[5] Given the extraordinary nature of these manifestations, it is difficult to believe that such a substance emerged at all and was taken seriously by some scientists and psychical researchers. Ectoplasm-producing mediums, most of whom were female, were undoubtedly perpetrating wholesale fraud. For this reason, an examination of these women’s performances and their productions may seem unnecessary and, in many ways, might confirm the suspicions of late Victorian and modern-day critics who suggest that such manifestations were expressions of some pathological disorder. I argue, however, that these women were in fact cannily negotiating the boundaries of female physiology, behavior, and agency. Indeed, the physical mediums of the late 19th and early 20th centuries ushered in a type of female subjectivity that defied scientific definition altogether. Physical mediums produced matter that was allegedly formed in the midst of a psychic state. The matter was often amorphous and the effort exerted in its production was, according to psychical researchers, wholly non-intellectual. While the intellectual labor of defining and evaluating the matter fell to the typically male researcher, the creative effort of self-definition ultimately fell to the medium.

[6] My examination of ectoplasm concerns the elusive knowledge that the medium’s body promised and the ways in which mediums created and manipulated this knowledge. Despite the prodigious mass of information that their observers produced, it was ultimately only the mediums themselves who really knewwhat had transpired. I argue that these women were unquestionably more in control of the narrative than either their observers or contemporary critics acknowledge or recognize and as such claimed a measure of agency uncommon to most women of this period. In staging their ectoplasmic manifestations these mediums were, for a time, able to invert the gendered hierarchies that existed in the scientific and para-scientific production of knowledge. Although these otherworldly performances were undoubtedly fraudulent and the mediums who produced them often relied upon erotic misdirection, this supernatural stage allowed these women to transgress rigid sexual and social boundaries, improve their material conditions and, for better or for worse, achieve celebrity status among scientists, Spiritualists, and psychical researchers.

[7] Thus far, critics have examined ectoplasm as a metaphorical substance and have subsequently separated the substance from the mediums who produced it. In his essay, “Phantom Images and Modern Manifestations” (1995) Tom Gunning notes that the appearance of ectoplasm “gave séances an oddly physiological turn” describing the medium’s function as one resembling an “uncanny photomat, dispensing images from orifices” (56, 58). Similarly, inPhantasmagoria (2006), Marina Warner describes ectoplasm as the “prime kind of developing agent for the other side” that allowed spirit forms to take shape (301). Focusing more on what the emergence of this peculiar manifestation signifies, Karl Schoonover suggests that it reflected the popular perception of the photographic process. In her book Vanishing Women: Magic, Film, and Feminism (2003), Karen Beckman examines the gendered dimensions of the séance room and relocates the vanishing woman of the magic show to the stage of the psychic parlor. Beckman suggests that the medium, in her production of ectoplasm, functions as a double of a photographic instrument “capable of reproducing intangible moving images that hover somewhere between life and death” (14). The ephemeral nature of the medium’s production leads to an “epistemological longing” that is never resolved, only reproduced (91). While such examinations are useful, the medium herself is obscured by the metaphorized substance she produces. This article is an attempt to rearticulate that connection. In doing so, I examine the ways in which the female body becomes a revered site for generating materialized ghosts and how these productions not only resist phallocentric conditions of knowledge but also undermine the foundations of this knowledge. Ectoplasm, while it might appear to be an embarrassing exudation at worst, is nevertheless a positively dissident substance. Finally, in reopening the medium’s cabinet I wish also to recover the lost histories of women whose lives have either largely been forgotten or their motives pathologized. Since mediumship and the knowledge that the séance room produced transformed significantly between the late 1880s and the 1920s and trends among mediums often spread beyond national boundaries, I examine a range of late nineteenth and early twentieth century mediums including the Italian Eusapia Palladino (1854-1918), the French Eva Carrière (1886-?), and the American Mina “Margery” Crandon (1889-1941). Beyond the manifestations themselves, I explore the gendered interactions among late 19th and early 20th century psychical researchers who claimed to know, the stage magicians and debunkers like Harry Houdini, who claimed to know better, and the mediums themselves who knew best what was happening in the medium’s cabinet.

Lying Bodies, Lying-in: The Strange Case of Eusapia Palladino

[8] In his book Thirty Years of Psychical Research, Charles Richet detailed his sittings with Eusapia Palladino, one of the most famous mediums of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Regarding Palladino’s gifts, Richet writes: “more than thirty very skeptical scientific men were convinced, after long testing, that there proceeded from her body material forms having the appearance of life, which I shall describe […] under the name of ectoplasms” (462). Indeed, it was Palladino’s manifestations that inspired Richet’s neologism. Palladino, born Raphael Delgaiz, was an impoverished and illiterate Neapolitan medium who exhibited psychic gifts at an early age. After losing both parents, the penniless Palladino served as a nursemaid for an upper-middle class family and later married an itinerant magician. During this period, Palladino performed the kind of paranormal feats that were fairly common in the 1870s: she levitated tables and produced spirit raps through the mediation of the omnipresent spirit guide, John King. In 1888, a professor by the name of Ercole Chiaia described Palladino’s gifts to Cesar Lombroso. The famous criminologist later agreed to take part in a séance with the medium during which he witnessed the inexplicable levitation of objects and afterward “consented to make the phenomena the subject of investigation” (39). In describing his sittings with Palladino, Lombroso not only notes changes in the medium’s appearance and demeanor but also comments upon the increase in Palladino’s menstrual discharge (112). The scientist further observes that as the medium enters into the trance state she “seems a prey to a kind of anger, expressed by imperious commands and sarcastic and critical phrases, and now to a state of voluptuous-erotic ecstasy” (113).

[9] Another member of Lombroso’s team of observers, Enrico Morselli, a psychiatrist and quondam skeptic, was not only convinced of the authenticity of Palladino’s psychic capabilities but also associated these gifts with physical and psychological abnormality. In his book,After Death—What?, Lombroso notes:

Morselli observed in her trance state all the characteristics of hysteria, namely, (1) loss of memory; (2) her personifications as John King, in whose name she speaks ; (3) passional acts, now erotic, now sarcastic; (4) obsession, especially in the shape of fear that she may not succeed in the séances; (5) hallucinations; and so forth. Toward the end of the trance, when the more important phenomena occur, she falls into true convulsions and cries out like a woman who is lying-in, or else falls into a profound sleep, while from the aperture in the parietal bone of her head there exhales a warm fluid, or vapor, sensible to the touch. (114)

Morselli’s characterization of the medium’s psychic performance as a form of hysteria echoes early critics of female Spiritualists who, by the 1870s, argued that spiritualism and mediumship were pathological expressions of hysteria. In his book The Physics and Physiology of Spiritualism (1871), the American neurologist William Alexander Hammond maintained that the “possessed—the ‘mediums’ of our day” served as excellent illustrations of “hysteria, chorea, and catalepsy” (43). Hammond describes the almost superhuman capabilities exhibited by allegedly hysterical women. One in particular manifested what Charcot termed the arc-de-cercle, by repeatedly arching her back until just her head and heels touched the bed. The neurologist also recounts the story of a medium who was guided by a “good” spirit control named Katy and a “bad” one she called “sailor-boy” who “took great delight in swearing through her, and in uttering such profane language as he had been accustomed to use on earth” (48). After presenting this case, Hammond asks: “Can any person familiar with the vagaries of hysteria doubt for an instant that this girl was suffering from it, and that her condition was aggravated by the notoriety which she gained by her performances?”(49). Interestly, the myopic Hammond sees no reward in the notoriety itself. Instead, his regard for the spiritually divided medium, a wayward soul with little capacity or inclination to act on her own behalf, reveals the common assumptions concerning mediumship, a practice founded upon the illusion of feminine passivity and female pathology. In 1873, Frederic R. Marvin, an American professor of psychological medicine, introduced “mediomania” as a specific type of hysteria that was primarily exhibited by female mediums. This late Victorian malady could, according to Marvin, eventually lead to a type of congenital degeneration that, in some ways, mimicked the effects of hereditary syphilis. Marvin argued that “mediomania in the first generation may become chorea or melancholy in the second, open insanity in the third, and idiocy in the fourth” (45).

[10] But female mediums were far from being the passive, pathological vessels that their admirers praised and their critics excoriated. Such spiritual performances gave the medium a stage and freedom from the constraints of social and sexual propriety. It is not surprising then that for men like Hammond and Marvin, mediumship was not just an odious fad; it was an infectious threat to the Victorian family and femininity. Under the aegis of Spiritualism, the medium could willfully impersonate vulgar sailors and, according to Marvin, abandon “her home, her children, and her duty, to mount the rostrum and proclaim the peculiar virtues of free-love” (38-39). Here Marvin implicitly links mediumship to the anxious claims made by critics of feminism and the New Woman. By the 1890s, however, the emergence of ectoplasm would transform the almost venereal corruption that was associated with mediumship. Ectoplasm- producing mediums, beginning with Eusapia Palladino, quite literally gave birth to what some scientists saw as a new biological order. This otherworldly generative function is evident even in Morselli’s description of the medium who, at the conclusion of her trance, cries out like a woman “lying-in.”

[11] In both Lombroso’s and Morselli’s description there is a sexual, if not orgasmic, element to Palladino’s process. According to Deborah Blum, Palladino had the habit of “climbing into the laps of the male” investigators (201). Ruth Brandon further asserts that Palladino would often sleep with any of the male sitters to whom she was attracted (130). Palladino’s performances eventually led Hereward Carrington, a British psychical researcher and later one of the medium’s most devoted investigators, to argue that there was a connection between the sexual response and psychic phenomenon. Indeed, in his bookThe Story of Psychic Science(1930) Carrington writes: “the production of physical phenomenon of exceptional violence has been coincidental with a true orgasm. From many accounts it seems probable that the same was frequently true in the case of Eusapia Palladino” (146). Curiously, Palladino’s later ectoplasmic manifestations took on a decidedly phallic character and one that was later adopted by other physical mediums. In describing one of Palladino’s ectoplasmic manifestations, Richet writes: “Once I saw a long, stiff rod proceed from her side, which after great extension had a hand at its extremity—a living hand warm and jointed, absolutely like a human hand” (477). Clearly, however, if mediums were producing manifestations that mocked phallic authority, the process by which they convinced investigators of the authenticity of these productions mocked the patriarchal orders that examined them.

[12] By 1895, Palladino had attracted the attention of the Society for Psychical Research (S.P.R.) which, after witnessing a parade of fraudulent materializations, understandably took a dim view of physical mediumship. During this particular investigation, Palladino familiarized herself with the researchers’ families and, in a telling act of impersonation, posed for a photograph wearing Henry Sidgwick’s professorial cap and gown (Blum 201). The sittings themselves were especially disastrous. Richard Hodgson observed the medium free a hand to move objects and use her feet to kick and animate the furniture. Palladino’s penchant for cheating at séances was almost as well-known as her baffling phenomena. In her own defense, Palladino often said that she would resort to cheating when the phenomena did not come: “Some people are at the table who expect tricks—nothing but tricks. They put their mind on the tricks, and I automatically respond. […] They merely will me to do them” (qtd. in Whitehead 450). Palladino was, however, able to convince other members of the S.P.R., including Frederick Myers and Oliver Lodge, of her capabilities as a powerful medium and the former joined Richet in Paris for a series of more successful sittings.

[13] What is interesting about Palladino’s champions is the ways in which they defended the medium when she was caught faking phenomena. Richet writes: “Simple rustics like Eusapia do not understand that the simulation of a phenomenon is a serious crime; they do not recognize the enormity of the fraud. […] A lengthy education is needed before they can be made to understand how odious and unpardonable is a lie that brings willful error into our poor efforts at truth” (457). Richet’s condescension highlights the disparity that existed between the illiterate Palladino and her educated bourgeois investigators. Palladino’s power, however, is evident in her ability repeatedly to outwit herds of her social superiors. This ability also earned her acclaim as a gifted medium and secured her financial independence. In another dubious defense of the medium, the biologist and vocal supporter of Spiritualism, Alfred Russel Wallace criticized the conjuror John Nevil Maskelyne for accusing Palladino of trickery in an 1895 séance. In a letter to the Daily ChronicleWallace writes: “It appears to me that accusations of wilful fraud, even against a medium, should be supported by all available facts, and by fair inference from them; and that this is not less incumbent on us when the accuser is a professional conjuror and exposer of mediums, and the accused is only an ignorant foreigner, and a woman.” The medium, however, was herself an accomplished conjuror, and very likely made use of such excuses, to say nothing of her séance room flirtations, in validating her phenomena. Palladino would fare better with other conjurors, however. Hereward Carrington, who was himself an amateur conjurer, took Howard Thurston, the renowned stage magician, to see Palladino perform. According to Carrington, Thurston was so impressed by the medium’s ability to levitate a table that he posted a $1000 challenge to any magician who could reproduce Palladino’s phenomenon under the same controls; no one could claim the reward (Essays in the Occult 35). Carrington and another conjuror would eventually investigate an American medium whose manifestations were even more remarkable than Palladino’s and whom I will discuss later.

Designing Women: The Collaboration of Eva C. and Juliette Bisson

[14] While their British counterparts remained faithful to an investigative process that placed physical space between the investigator and the medium, continental psychical researchers dispensed with such physical distances and would often remain in very intimate proximity to their subjects of study. This type of intimacy is captured in photographs of psychologist and psychical researcher Baron von Schrenk-Notzing’s sittings with Eva C., a physical medium whose materializations had attracted the attention of a number of scientific men. Schrenck-Notzing’s book Materialisations-Phanomene, originally published in Germanyin 1913, was later translated by E. E. Fournier d’Albe and published in 1923. Eva C., whose full name was Eva Carrière (her given name was Marthe Béraud), cultivated her gifts as a medium shortly after the death of her fiancé at the urging of his parents.

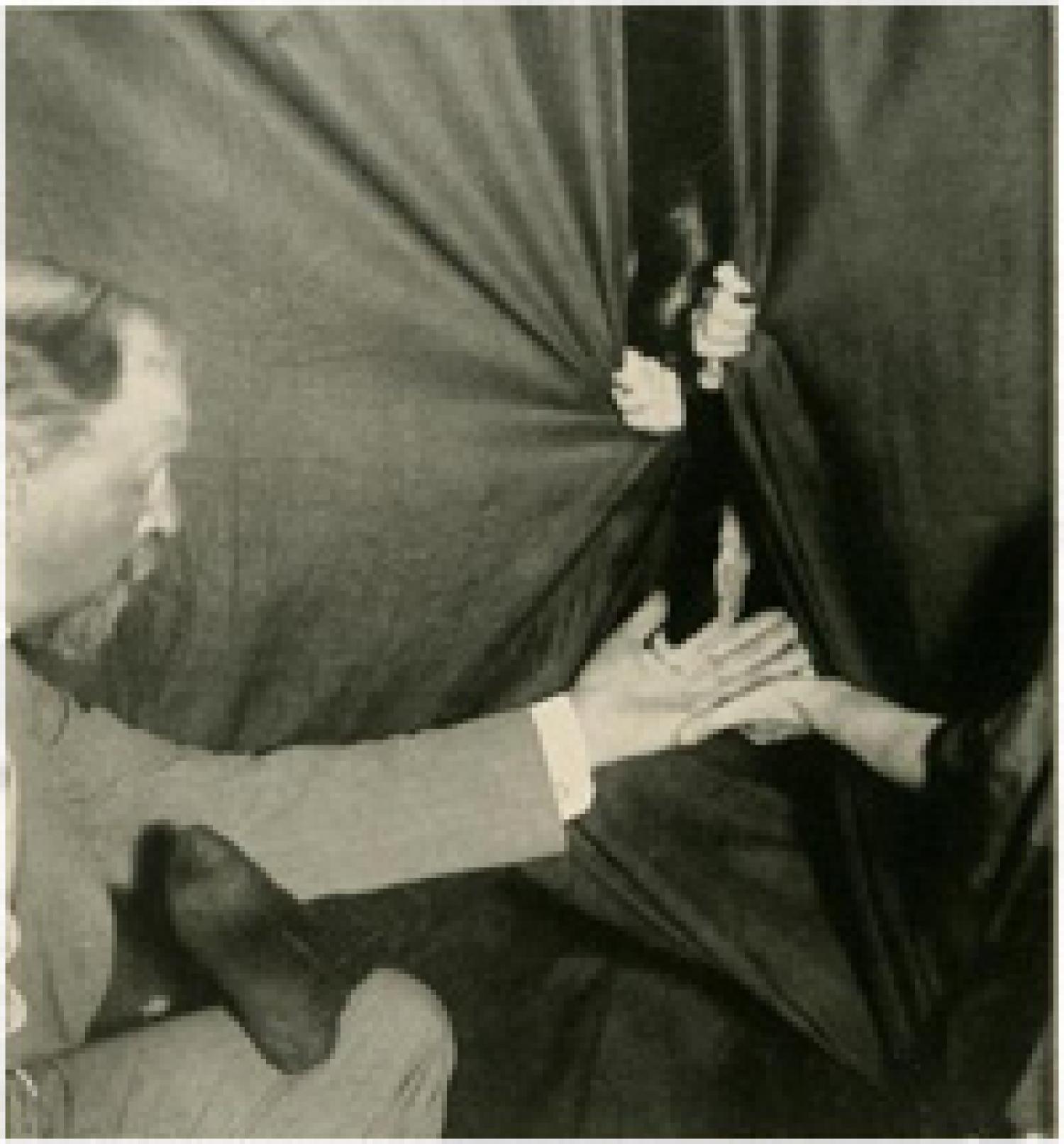

Figure 1: A flashlight photograph of Eva producing ectoplasm from the medium’s cabinet. Schrenck-Notzing appears on the left. Image courtesy of Hathi Trust.

During her performances, Eva brought forth a phantom by the name of “Bien Boa,” the good snake, a Hindu spirit guide who had, according to Eva, died 300 years earlier. Between 1902 and 1905, Richet observed and photographed a series of visitations from Bien Boa. In Richet’s photographs, the phantom is seen emerging from behind a curtain that enclosed a makeshift cabinet. The materialization is not as spectral as one would imagine. The figure is draped in a white sheet and is inexplicably helmeted. The bushy beard slipping independently from the figure’s face is perhaps the most curious feature of the photographed visitation. However, Richet was satisfied with the sitting and Bien Boa’s subsequent materialization. Richet published his account of the event in the Annales des Sciences Psychiques, a magazine that he had founded, and the account attracted even more scientific observers. Eva’s sittings with Schrenck-Notzing occurred nearly five years after Richet’s visit and these sittings produced the most unusual supernatural traffic. Working with the sculptor and psychical researcher, Juliette Bisson, the respectable widow of playwright Alexandre Bisson, Schrenck-Notzing photographed and examined ectoplasmic materializations, the variety of which had not yet been encountered. These materializations occurred in a room that appeared to be a cross between a late Victorian medical clinic and a provisional photo lab (see figure 1). Because of the sensitive nature of ectoplasmic material, only red light was used in each sitting. The development of ectoplasm, it seems, was very similar to the process used in developing photographs; indeed, Schrenck-Notzing notes that “the necessary dark room was furnished by the cabinet” (21).

[15] But this dark room and the sittings themselves often took on an explicitly pornographic dimension as well. In his account of a 1911 sitting, Schrenck-Notzing lists the other sitters present then describes the conditions of the event, noting that a “complete, including gynaecological, examination” of the medium had been performed before it commenced (84). During this sitting, at the repeated urgings “donnez-donnez” (give-give) from the crowd of sitters, Eva produces ectoplasmic limbs from behind the curtain of the medium’s cabinet. The ectoplasm stretched from the cabinet and made contact with Schrenck-Notzing’s forehead. The doctor writes “I distinctly felt the pressure as from a soft finger-tip, together with the feeling of cool and moist human skin” (84). During this exchange the medium instructs the doctor to photograph the event with the command: “prenez-le” (take it). Although the photographs reveal nothing, Schrenck-Notzing is encouraged by his contact with the ectoplasm.

[16] Before Schrenck-Notzing wakes Eva from her trance, the medium makes a series of unusual requests. She asks Bisson to remove the stitching between her leotard and dress, a sort of hybrid garment specifically designed to prevent fraud, then invites Schrenck-Notzing to examine her. The doctor provides the following account of this examination: “In the course of the gynecological examination I introduced the middle finger of my hand pretty deep into the vagina, without, however, finding anything beyond a softening of the epithelium. It is, therefore, certain that the genital passage was not used as a hiding place” (84). While the exam convinces Schrenck-Notzing of Eva’s honesty, it appears to be quite unnecessary. As the doctor notes at the beginning of the entry, a gynecological examination had already been performed.

[17] The medium’s request for another examination appears to be designed to elicit a number of different responses from Schrenck-Notzing. Eva, in anticipation of the doctor’s interpretation of an event that created sensation but failed to establish proof, relies upon the truth that her body will tell. She indulgently defers to Schrenck-Notzing because of his official capacity as a doctor and a scientist. But to a certain degree, the request to be examined also serves as a sort of seduction and clever misdirection. While some critics characterize Eva’s willful submission to if not eager desire for extensive gynecological exams as proof of a complicated and extensive neurosis, it is clear that the participants in this peculiar type of sitting are also implicated in an eroticized, if otherworldly, event (see Brandon 151-52).

[18] On some level, the medium performs a type of striptease for a titillated crowd that likes to watch. Such voyeurism is heightened for the researchers compiling the data. Indeed, in his book, Schrenck-Notzing carefully notes the intimate details of Eva’s life—commenting upon when Eva has visitors and when she is visited by her confounding monthly menses. In his study, Schrenck-Notzing also includes a number of Juliette Bisson’s rather colorful and sexually charged accounts of her personal encounters with Eva’s ectoplasm. Bisson sends the following account of materialization in a letter to Schrenck-Notzing:

On my expressing a wish, the medium parted her thighs and I saw that material assumed a curious shape, resembling an orchid, decreased slowly, and entered the vagina. During the whole process I held her hands. Eva then said, ‘Wait, we will try to facilitate the passage.’ She rose, mounted on the chair, and sat down on one of the arm-rests, her feet touching the seat. Before my eyes, and with the curtain open a large spherical mass, about 8 inches in diameter, emerged from the vagina and quickly placed itself on her left thigh while she crossed her legs. I distinctly recognized in the mass a still unfinished face, whose eyes looked at me. (116)

In her individual sittings with Eva, Bisson often led the naked medium into a sort of trance. Whether it was the absence of the restricting leotard or the erotic energy between the two women, these sittings often produced the most notable results. What seems clear is that Bisson, in her self-appointed position as Eva’s ectoplasmic midwife, knew how these extrusions were really made. What also comes through in her accounts of these manifestations is the intimacy that Bisson shares with the medium. In another letter to Schrenck-Notzing, only months after the previous one, Bisson writes the following:

Yesterday I hypnotized Eva as usual, and she unexpectedly began to produce phenomena.

As soon as they began, Eva allowed me to undress her completely. I then saw a thick thread emerge from the vagina. It changed its place, left the genitals, and disappeared in the navel depression.

More material emerged from the vagina, and with a sinuous serpentine motion of its own it crept up the girl’s body, giving the impression as if it were about to rise in the air. Finally it ascended to her head, entered Eva’s mouth, and disappeared.

Eva then stood up, and again a mass of material appeared at the genitals, spread out, and hung suspended between her legs. A strip of it rose, took a direction towards me, receded and disappeared. All this happened while Eva stood up. (134)

There are many layers of seduction at work here. There is Bisson’s seduction of Eva, Eva’s seduction of Bisson, and Bisson’s and Eva’s seduction of Schrenck-Notzing—a powerful enticement that at once confirms his faith in the validity of Eva’s productions while offering him a private view of Bisson and Eva’s intimate encounters. Ultimately, however, it is Bisson and Eva who are responsible for the creation of this ectoplasmic birth, a phenomenon that conformed to conventional expectations of women’s bodies, yet defied interpretation.

[19] The static nature of Bisson’s and Schrenck-Notzing’s photographs fails to communicate the activity of these productions. What is evident in Bisson and Schrenck-Notzing’s descriptions and missing in the photographs of these sittings is the medium’s body as a naked display. While there are photographs of a nude Eva emerging from her cabinet and others that feature strings of ectoplasm hanging like a bundle of limp noodles from the medium’s breasts, other physical elements that define Eva’s as a female body are often rubbed out. The curve of the medium’s breasts, the darker skin of her nipples, even the pubic thicket from which countless ectoplasmic heads emerged are erased through photographic retouching, giving the medium’s body a boyish and bone-white appearance. Such sanitized photographs, however, are mixed in with others that present Eva’s body in an unedited state. In one two-page photograph, the medium’s nude torso, bearing the stringy evidence of a recent materialization, appears as a crude centerfold near the middle of Schrenck-Notzing’s book. These inconsistent photographic alterations, coupled with Schrenck-Notzing’s detailed, voyeuristic accounts of the phenomena reveal the medium’s body as a queer, mutable object that serves as the nexus between normal and supernormal, sexed and unsexed, male and female.

Figure 2: Eva C.’s ectoplasmic finger. Image courtesy of Hathi Trust.

[20] To a certain extent, the medium’s nude body is itself ectoplasmic and ephemeral and the ectoplasm is occasionally pornographic. On April 1, 1913, and in the absence of Schrenck-Notzing, Eva produced an ectoplasmic finger. Bisson describes the materialization as follows: “Several times, the finger appeared and disappeared. A piece of the substance showed itself on the right side of Eva’s belly; […] Madame B. flashed light on the phenomenon with a flashlight; Eva herself took the flashlight and shined the light toward the manifestation. Then the photograph was taken” (Les Phénomènes Dits de Matérialisation; Étude Expérimental 192; translation mine). A portrait of the medium and her manifestation appears on the page preceding Bisson’s description, but Bisson also devotes an entire page to an enlarged view of the manifestation itself. The effect is curious. In isolation from the medium, the ectoplasm appears to be a rudimentary, deflated, and disembodied phallus—quite possibly a pornographic April Fools’ joke at Schrenck-Notzing’s expense (see figure 2). Although it is impossible to say with any certainty what Bisson and Eva hoped to achieve in this sitting and with the photographs that document it, the manifestation could be read as a pointed critique of Schrenck-Notzing’s clinical phallocentrism and a parody of, in this case impotent, male authority in general.

[21] While Bisson’s role in the creation of these ectoplasms has never been completely elucidated, several photographs revealing the spurious nature of Eva’s materializations were found among the aforementioned Dr. Geley’s papers after his death in 1924. These photographs also indicate that Bisson willfully collaborated with Eva in staging such manifestations (Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology 522). Indeed, it is likely that Bisson’s and Eva’s collaboration went beyond the medium’s cabinet. However, for some critics, the conspiracy between the women was the result of a romantic relationship. In her study of 19th and 20th century spiritualism, Ruth Brandon confidently asserts that “Juliette Bisson and Eva C. almost certainly had some sort of sexual relationship” (160). Brandon also argues that the confederacy between Bisson and the “hysterical, rather plain” Eva is somehow inexplicable, noting that “people defy any possible logic for a lover” (160). Bisson’s active involvement in duping the many scientists who endorsed Eva’s materializations is similarly explained away, if not completely denied, in several newspaper accounts of the medium’s 1922 sittings with scientists from the Sorbonne. After thirteen sittings that produced no results and two that resulted in the convulsive production of gray vomit, “a substance,” the men bizarrely note, “which possesses no mobility of itself,” the Sorbonne scientists dismissed Eva’s ectoplasmic phenomena altogether (“Sorbonne Scientists” 1).

[22] However, despite their dismissal of Eva’s phenomena, at the conclusion of a New York Times article about the investigation, “Sorbonne Scientists Find No Ectoplasm after Experiments in Fifteen Séances,” the professors reportedly “pay a tribute to the scientific ardor of Mme. B. [Juliette Bisson] and her absolute good faith” (1). In another article that appeared in the New York Times a few weeks later, “Ectoplasm, Myth or Key to the Unknown?” Joseph Jastrow, a psychologist and critic of psychical research, characterizes Bisson as “the young woman’s sponsor” who should be “commended for her good faith” and whose “implicit trust in the medium is well known” (88). Bisson was beyond reproach for early 20th century and recent critics alike. Her class position absolves her of any willing involvement in the machinations of a young medium. However, Bisson’s extensive and tireless contribution to Eva’s materializations is quite evident in Schrenck-Notzing’s and her own record of these events. What seems curious is the response from Eva’s critics. While such critics expect fraud from the young medium, they do not expect it from the older, wealthier Bisson. As noted earlier, Bisson’s collaboration with Eva, at least for some critics, appears to be the result of her romantic attachment to the medium. Bisson, it would seem, was duped into loving Eva and afterward willingly duped the scientists who studied the medium.

[23] Bisson’s collaboration with Eva did not go unnoticed by all psychical researchers. In 1920, Bisson, after some hesitation, permitted Houdini, a vocal critic and unremitting debunker of spirit mediums, to attend one of Eva’s performances “showing the phenomena of materialization” (Houdini 167). The antipathy that existed between Bisson and Houdini, at least as far as the latter was concerned, was borne out of Bisson’s contempt for stage magic and prestidigitators. In her letter of invitation to Houdini, Bisson tells him “I have always refused to admit to my house, an ordinary prestidigitator, or even one of better rank. Our work is serious and real, and the gift of Mlle. Eva might disappear forever, if some awkward individual insists on thinking there is fraud involved, instead of real and interesting facts, which especially interest the scientific” (167).

[24] Despite Houdini’s reputation, Bisson welcomes him to the séance and suggests that Eva’s gift, unlike that of the magician’s, is uncontrived and depends upon “allowing the forces of nature to act” (167). Bisson’s distinction between the inexplicable acts of the medium and those of the stage magician is significant since the success of each performance rests upon the often flawed perceptions of those who witness it. But while the magician’s audience engages in a willing suspension of disbelief, the medium’s audience is confounded by their will to believe. The difference between these performances resides in the fact that the medium’s body reveals allegedly supernatural matter whereas the magician’s body conceals or manipulates natural matter; he misdirects with his patter—she with her body. However, deception was characteristic of both the magician’s act and that of the medium. In his account of the séance, Houdini notes that while the medium was examined, all “orifices of her body” were not checked (169). During the séance, Eva successfully produces a “white plaster and eventually managed to juggle it over her eye” (169). The materialization was of a two dimensional illustration that appeared to be “a colored cartoon and seemed to have been unrolled” (170). Eva later produces an object from her mouth that appears, at least to Houdini, to be a “rubber ball.” The materialization soon mysteriously disappears to the amazement of all observers but one. Houdini, in accounting for the disappearance, notes, “my years of experience in presenting the Hindoo needle trick convinced me that she ‘sleight-of-handed’ it into her mouth while pretending to have it between her fingers” (169). Without giving away the secret of his own trick, Houdini tells his readers that the illusion is accomplished quite naturally adding that “over a thousand physicians” observed the trick and were “unable to explain it” (169). Houdini further suggests, in his characteristic Vaudevillian patois, that Eva’s manifestations might be the result of an “inside job” adding “I regret that I do not believe Mme. Bisson entitled to a clean bill of health…in my estimation she is a subtle and gifted assistant to Eva whom I do not believe to be honest” (172). He leaves the séance convinced that both women had taken “advantage of the credulity and good nature of the various men with whom they had to deal” (172).

[25] Given the constraints of femininity at this historical moment, however, and the very real material concerns for women like Eusapia Palladino and Eva C., these manifestations are not, as Houdini would have it, simple, misguided deceptions. Rather, such manifestations are shrewd acts of defiance and self-preservation that ultimately exposed the inadequacy of positivist science as well as the assumptions of psychical research. Their mediumistic performances not only gave Palladino and Eva C. financial independence, it also gave them a stage that was reserved for the (typically) male magician. Like the stage magicians, mediums employed misdirection and confederates in manifesting their phenomena. The crucial difference between the phenomena produced by magicians like Houdini and those of the mediums was that the latter capitalized on validating the widespread interest in otherworldly communications, communications for which women were believed to be particularly well-suited. Beyond providing mediums with lucrative careers, such manifestations also secured them celebrity status comparable to that of their illusionist counterparts. Indeed, celebrity seems to have motivated the manifestations of middle-class mediums like Margery Crandon, “the Blonde Witch of Beacon Hill.”

Female Trouble: “The Blonde Witch of Beacon Hill”

[26] After the Sorbonne scientists’ verdict on Eva’s case, Bisson and the medium parted ways, the latter married, the former disappeared. The craze for ectoplasm seemed destined to die out. Instead, the production of the material continued and garnered the steady attention of the press. In 1922, The Scientific American announced a $2,500 reward to the “first person who produces a psychic photograph” and $2,500 to the “first person who produces a visible psychic manifestation of other character” (“Fixes” 12). Conan Doyle believed that the Scientific American’s offer would ultimately have a deleterious effect upon the field of psychical research and argued that “a large money reward will stir up every rascal in the country while the best type of medium is unworldly and would not be attracted by such a consideration” (“Sees Evil” 29). However, Conan Doyle’s well-heeled and highly moral medium was soon to emerge.

[27] After encountering a few “rascals” who fraudulently produced a range of tangible items including ectoplasm, the Scientific Americancommittee finally thought they had found a medium who might be genuine. The medium’s name, or at least the name that the investigators had given her, was Margery and in the preemptively published opinion of the committee’s secretary, J. Malcolm Bird, the medium had a shot at winning the $2,500 prize. In his description of Margery, Bird notes that “she is the wife of a professional man and is in comfortable circumstances,” and is “a woman of culture, position and means, with an apparent horror of notoriety” (“Woman Astounds” 1). Bird includes this information in order to silence critics, like Conan Doyle, who saw the cash reward as a motivating force in the production of psychic phenomenon. Bird also notes that the medium and her husband not only paid the investigator’s expenses, but invited them to stay at their house. While this generosity is remarkable, Bird’s inclusion of such details tacitly suggests that the medium involved is of a higher class and is consequently more credible. The medium’s gifts as a host of both mundane and otherworldly guests would become a good deal more interesting as the investigation progressed.

[28] The committee members included Bird, Hereward Carrington, psychologist William McDougall, Houdini, physicist Daniel Comstock, and American Society for Psychical Research (A.S.P.R.) officer, Dr. Walter Franklin Prince. Bird took it upon himself to provide early reports of the committee’s investigation and was responsible for newspaper headlines that touted Margery’s gifts. The interest generated by these stories led a few enterprising journalists to uncover the identity of the medium who appeared to be nothing less than a phenomenon. In an August 1924 headline from the New York Times Margery is identified as Mina Crandon, wife of a Boston physician and former Harvard professor. Although these early articles stress the medium’s respectability, Mina’s personality and ectoplasmic productions would soon eclipse such prosaic qualifications.

[29] While facts about Mina’s early life are sparse, we know that she was born in Princeton, Ontario, in 1888. In 1911, her older brother, Walter, died in a railroad accident; he would eventually become a central part of Mina’s paranormal performances. Mina married a local grocer and eventually divorced him in 1918, four years after the birth of a son. She remarried Dr. Le Roi Goddard Crandon soon after and relocated to Boston. It was her husband’s interest in the paranormal that led Mina to her first séance and there she linked hands with a group of casual investigators. In his biography of Crandon, Thomas R. Tietze writes: “Suddenly, there was a motion. Instantly, all attention riveted on the wooden table before them. It slid laterally, very slightly, but perceptibly. Then it rose on two legs and fell to the floor with a crash” (18). In an attempt to identify the “psychic” among the sitters, each member left the circle and when Mina left, the table stood still. So began Mina’s career as Margery. Tietze argues that “Margery’s” phenomena were most likely the result of insecurities surrounding the relationship she shared with her husband: “Mina was painfully aware of her intellectual inferiority to her husband” and “was unsure of her husband’s fidelity” (19). Nevertheless, Margery/Mina was responsible for a number of remarkable material fictions and Tietze’s characterization of her seems unfair if not substantially inaccurate. During an early investigation, the committee from theScientific American encountered the voice of Walter, Mina’s deceased brother. The voice that issued rather mysteriously from the entranced medium was loquacious, playful, and fond of rough language. Bird notes that the spirit made contact with the sitters through the use of what Walter and his friends ingenuously referred to as ectoplasm. The sensations that investigators experienced during these sittings were described as “soft pinches, caressing fingers, […] a hard fist, […] kissing lips” (“Woman Astounds” 1). Such descriptions illustrate the ironically physical intimacy that characterized otherworldly communications.

[30] After independently publishing a favorable report of the Margery phenomenon, Bird drew fire from Harry Houdini, the one committee member who had not taken part in the sitting. Houdini made a trip to Boston in order to prevent what he saw as the inevitable embarrassment of the committee members and Scientific American. After several inconclusive sittings and Bird’s eventual resignation from the committee, Houdini proposed to construct a box that would insure the integrity of the manifestation. The sitting medium’s head and arms would protrude from the box, but the rest of her body would be restrained. The medium had to ring the bell in a contraption that was placed on a table in front of her. To Houdini’s surprise, the bell rang. When the room was again lit, the sitters discovered that the lid of the cabinet was open. Mina claimed that it was Walter who broke the lid; Houdini thought otherwise. Spurred on by yet another inconclusive sitting, Houdini reinforced the lid with “four hasps, staples and padlocks in such a way there would be no possible chance of the lids being forced open again” (152). The account of what happened next is still up for debate.

[31] Sometime after the investigators locked the medium in the cabinet, Walter gruffly addressed the magician, “Houdini, you are very clever indeed but it won’t work. I suppose it was an accident those things were left in the cabinet” (156). When Houdini asked what had been left in the cabinet, the voice replied that there was a ruler beneath a pillow on the floor of the cabinet and accused Houdini of planting it. After making this accusation, Walter roared “Houdini, you God-damned bastard, get the hell out of here and never come back. If you don’t, I will” (156). In his pamphlet on the “Margery” investigation, Houdini includes illustrations of how the medium might have used the ruler to affect the phenomenon the sitters anticipated. Houdini leveled his suspicion at the Crandons. However, according to Houdini’s biographer, William Gresham, many years later, Houdini’s assistant claimed to have planted the ruler at his employer’s request in order to discredit Margery. This sitting seemed to have a catastrophic effect on the investigation. TheScientific American committee remained deadlocked: Dr. Comstock believed that “rigid proof” had not been presented; Dr. McDougall was certain that the phenomena were “produced by normal means”; Dr. Prince believed that it was a “normal and deceptive production”; Houdini argued that it was a “deliberate and conscious fraud”; Carrington believed that although there was the possibility of some fraud, there was “genuine phenomena” as well: and Bird, although no longer a member of the committee, remained “Margery’s” fiercest supporter (Prince 435). Needless to say, “Margery” failed to win the prize.

[32] Without an account of Mina’s own perspective on the investigations and her mediumship, we are left to speculate about the nature of her relationship with her sitters, her husband, and her spirit guide. “Margery,” by all accounts, appeared to deal with her critics gracefully. If, as some critics aver, Mina concocted these extensive and increasingly bizarre manifestations in order to secure her husband’s fidelity, it seems strange that she would do so using Walter’s voice rather than using that of a seductive female. Tietze suggests that “[Mina] had practically no sense of the history in which she lived and only a vague suspicion that she was gaining a great deal of heartily welcome attention” (Margery xx). But this conclusion is troublingly inadequate if not patently wrong. In Walter, Mina had constructed a relatively complex character who spoke to the hopes and fears of those who encountered him. Beyond that, however, this entity, supernatural or otherwise, allowed her to challenge her male investigators in a manner not available to a woman of her position and endowed her with a type of authority that would otherwise have been usurped by her much older husband. As for her ectoplasmic materializations, these would eventually take on the reproductive quality of Eva’s gynoplastic creations.

[33] Despite less than satisfactory results with the Scientific American, the “Margery” mediumship piqued the interest of the British S.P.R. and soon a new class of manifestations developed. Dr. E. J. Dingwall headed an investigative team that included Dr. McDougall, a member of the previous investigation, and Dr. Ellwood Worcester. During this 1925 investigation, Margery produced the expected phenomena: Walter’s voice came through during the sittings and the medium effectively moved a variety of objects using telekinesis. What is most striking about this particular investigation, however, is the appearance of a crudely constructed ectoplasmic hand. While the earlier ectoplasmic manifestations of other mediums took on the appearance of string, muslin or melted wax, Margery produced a pink spatulate hand that was connected to a slender, ribbed wrist. Dingwall was most impressed with the fact that Margery appeared to have given birth to the hand.

[34] After witnessing its emergence, Dingwall excitedly penned a letter to Schrenck-Notzing, noting: “It is the most beautiful case of teleplasm and telekinesis with which I am acquainted. […] The materialized hands are connected by an umbilical cord to the medium; they seize upon objects and displace them” (qtd. in Brandon 186). As was custom with events of this sort, the hands were quickly photographed. What is interesting about these photographs, aside from the fleshy club-like ectoplasm, is the intimate if not erotic juxtaposition of the medium’s body with that of the investigator. Margery’s lower body is nude and there is a handkerchief inadequately covering her genitals. Above this is Dingwall’s hand, apparently being held in place by Margery’s and the ectoplasmic hand atop his. Dingwall’s excitement over Margery’s manifestation was very likely inspired by more than just the pure motives of psychical research. Although the hand allegedly emerged from the medium’s navel, Dingwall interprets its appearance as a type of birth. The organ-like structure of the hand and wrist drew criticism from McDougall and even the once delighted Dingwall began entertaining some doubts about its authenticity. In his own report of the phenomenon, McDougall notes that the hand appeared to be “the lung of some animal surgically manipulated to resemble roughly in shape a human hand” (“Margery Mediumship” 198). He further asserts that “Margery’s” ectoplasm “issu[ed] on some, and, probably all occasions [from] one particular ‘opening in the anatomy’”—presumably, the vagina (199).

[35] Some of her critics speculated that Margery’s husband may have procured the animal tissue; still others like Harvard investigator Grant Code theorized that Dr. Crandon altered Mina’s anatomy so that it could produce these ectoplasms. Such productions led to other more unsavory bits of gossip concerning the “bizarre tastes and grotesque goings-on, both in an out of the séance room” at the Crandons’ home (Gresham 246). Gresham also suggests that Houdini had “information about [Crandon] that she was not eager to have him circulate” (255). The nature of these “goings-on” remains a mystery, like most things concerning the Crandon case. However, individual accounts of these sittings and the nature of the ectoplasm produced take on even more lurid dimensions. In a 1959 article for Horizons magazine, historian Francis Russell recounts the confessions made by an acquaintance who attended several of Margery’s séances. According to Russell, the man described one of Margery’s manifestations as follows: “Margery produced an ectoplasmic hand and we were asked to feel it. As soon as I touched it I knew it was the hand of a dead person. It was small, either a child’s or a woman’s, but dead. I understood then. Dr. Crandon was a surgeon, and he could sneak such things out of the hospital” (110).

[36] In January 1926, a group from the A.S.P.R. under the direction of Henry Clay McComas, a psychologist from Johns Hopkins, visited the Crandons for another sitting. McComas brought with him another psychologist, Knight Dunlap, and physicist Robert W. Wood, a man who had become known for his pioneering work in infrared and ultraviolet photography. This new group of sitters was a good deal more skeptical of mediumistic phenomena than their predecessors. Indeed Dunlap had one year earlier asserted in his book Old and New Viewpoints in Psychology that if a medium claimed that phenomena was produced by anything other than the living, “she is a fraud and nothing she produces is to be taken as other than deliberate fraud” (qtd. in Christopher 217). In “Science: Margery Plays Cards,” a 1938 article that appeared inTime magazine, the author describes McComas as a man “whose hobby is exposing mediums.” The same description could easily have been applied to Wood who had in 1909 tried to catch Eusapia Palladino in fraud. Wood’s plans were frustrated when the medium, upon realizing his intentions, feigned illness (217). During one of the sittings, Wood was prodded by an ectoplasmic rod that had emerged from the medium’s lap. Upon gripping the rod, he yelled out: “The whatcha-ma-call-it feels to me like a ——” (qtd. in Christopher 218). The disgusted Crandon, who reported the embarrassing situation in his letter to the A.S.P.R., avoided including the term Wood used to describe the rod and further noted: “A true scientist would have described the terminal as to its length, breadth, thickness, temperature, degree of hardness and softness” etc. (qtd. 218). The committee later concluded that the ectoplasmic rod was an animal intestine that had been “stuffed with cotton and stiffened with wire” (“Science”).

[37] While it is possible that Dr. Crandon served as “Margery’s” accomplice, or that “Margery” was seduced by the notoriety that these manifestations earned her, we are still no closer to the certainty to which psychical research aspired. Even the shifting nature of Mina/Margery/Walter’s identities seems to reflect the indefinable nature of the matter that this article addresses. Ectoplasm mirrors the unstable era in which it emerged. But ectoplasm also, by its very elusive and indefinable nature, allowed female mediums of the period to redefine themselves and also to expose the limits of positivist and psychical knowledge. While we, unfortunately, have no way of knowing what motivated these mediums, it is not beyond the realm of possibility that their ectoplasmic protuberances materialized as a means of prodding back at their examiners and at the boundaries of polite society. Palladino’s séance room performances allowed her both social and sexual mobility while the cross-class collaboration between Eva C. and Juliette Bisson helped the women not only to defy Schrenck-Notzing’s clinical authority but also to achieve recognition among Spiritualists and psychical researchers alike. Mina Crandon’s motivations seem somewhat more complex. In contemporary novels like Joseph Gangemi’s Inamorata (2004) and William Hjortsberg’s Nevermore(1994), Margery’s air of mystery pervades the fiction as it seems to have done in real life. Margery, like Houdini, took her secrets to the grave. While she was on her death bed, Nandor Fodor, who had been a friend of the medium, asked Mina how she produced the phenomena that she did. Mina responded somewhat warily, “all you ‘psychical researchers’ can go to hell” then playfully added “why don’t you guess? You’ll all be guessing…for the rest of your lives” (Margery 184-85).

Acknowledgements. I’d like to thank my intrepid co-directors, Purnima Bose and Joss Marsh, as well as Laila Amine, Rebecca Baumann, Karen Dillon, Tanisha C. Ford, and Ursula McTaggart for their valuable feedback on the various incarnations of this article.

Works Cited

- Barnard, Guy Christian. The Supernormal: A Critical Introduction to Psychic Science. London: Rider & Co., 1933. Print.

- Beckman, Karen. Vanishing Women: Magic, Film, and Feminism. Durham: Duke UP, 2003. Print.

- Bisson, Juliette. Les Phenomenes Dits de Materialisation, 1921. WikiSource. Web. 5 May 2010.

- Blum, Deborah. Ghost Hunters: William James and the Search for Scientific Proof of Life After Death. New York: Penguin Press, 2006. Print.

- Brandon, Ruth. The Spiritualists. New York: Alfred E. Knopf, 1983. Print.

- Carrington, Hereward. Essays in the Occult. New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1958. Print.

- —–. The Story of Psychic Science. New York: Ives Washburn, 1931. Print.

- Christopher, Milbourne. Mediums, Mystics & the Occult. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1975. Print.

- Conan Doyle, Arthur. The Edge of the Unknown. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1930. Print.

- Farrington, Elijah. Revelations of a Spirit Medium, 1922. Internet Archive.Web. 19 Sept. 2008.

- “Fixes Rigid Rules for Psychic Tests.” New York Times. 15 Dec 1922:12. ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Web. 10 Nov. 2008.

- Fodor, Nandor. Between Two Worlds. West Nyack, NY: Parker Publishing, 1964. Print.

- —–. The Haunted Mind. New York: Garret Publications, 1959. Print.

- Geley, Gustave. From the Unconscious to the Conscious. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1921. Print.

- Gunning, Tom. “Phantom Images and Modern Manifestations: Spirit Photography, Magic Theater, Trick Films, and Photography’s Uncanny.” Fugitive Images: From Photography to Video. Ed. Patrice Petro. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1995. 42-71. Print.

- Hammond, William.The Physics and Physiology of Spiritualism, 1871.Internet Archive. Web. 11 Oct. 2008.

- Houdini, Harry. A Magician Among the Spirits. New York: Arno Press, 1972. Print.

- Jastrow, Joseph. “Ectoplasm, Myth or Key to the Unknown?” New York Times. 30 Jul 1922: 88-89. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.Web. 10 Nov. 2008.

- Lodge, Oliver. Past Years: An Autobiography, 1931. Google Book Search. Web. 10 Nov. 2009.

- Lombroso, Cesare. After Death—What?: Spiritistic Phenomena and Their Interpretation. New York: Small, Maynard, and Co. 1909. Print.

- McDougall, William. “The ‘Margery’ Mediumship.” Journal of the American Society for Psychical ResearchVolume 19, 198-199 1925. Print.

- Marvin, Frederic R. The Philosophy of Spiritualism and the Pathology and Treatment of Mediomania. Two Lectures Read Before the New York Liberal Club. New York: Asa K. Butts & Co., 1874. Print.

- Myers, FWH. The Survival of Human Personality after Bodily Death.New York: Longmans Green, 1903. Print.

- Prince, Walter Franklin. “A Review of the Margery Case.” The American Journal of Psychology. Jul., 1926: 431-441. JSTOR. Web. 5 May 2010.

- Richet, Charles. Thirty Years of Psychical Research. Trans. Stanley DeBrath. New York: Macmillan, 1923. Print.

- Rinn, Joseph F. Sixty Years of Psychical Research. New York: Truth Seeker Press Company, 1950. Print.

- Schoonover, “Ectoplasms, Evanescence and Photography.” Art Journal, Vol. 62, No. 3 (Autumn, 2003): 31-43.JSTOR. Web. 25 May 2010.

- Schrenk-Notzing, Albert von. The Phenomena of Materialisation. London, 1920. Reprint, New Hyde Park, N.Y.: University Press, 1975. Print.

- “Science: Margery Plays Cards.” Time. 21 February 1938: n.p. Time Magazine Online. Web. 29 May 2010.

- “Sees Evil in Reward of $5,000 for Spirit.” New York Times. 10 Dec. 1922: 29. ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Web. 3 June 2008.

- “Sorbonne Scientists Find No Ectoplasm After Experiments in Fifteen Séances.” New York Times. 8 July 1922: 1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Web. 4 July 2008.

- Tietze, Thomas R. Margery: An Entertaining and Intriguing Story of One of the Most Controversial Psychics of the Century. New York: Harper & Row, 1973. Print.

- Wallace, Alfred Russel. “To the Editor of the Daily Chronicle.” The Daily Chronicle. 1 Nov. 1895. Print.

- Warner, Marina. Phantasmagoria. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006. Print.

- Whitehead, George. An Inquiry into Spiritualism. London: J. Bale, Sons and Danielson, 1934. Print.

- “Woman Astounds Psychic Experts.” New York Times. 19 June 1924: 1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Web. 3 June 2008.