Are You Finally Comfortable in Your Own Skin?: The Raced and Classed Imperatives for Somatic/Spiritual Salvation in The Swan

[1] When Sylvia is selected to be a contestant on Fox’s makeover and pageant reality show The Swan, we are told that she has faced a lifetime of romantic rejection because of her appearance. In documentary-style footage, Sylvia critiques her bikini-clad body in front of a mirror, speaking of her desires for smaller thighs and less pronounced ears. Sylvia’s boyfriend provides additional testimony, acknowledging they have a limited sex life because of Sylvia’s body issues. “It’s always been a challenge for Sylvia to stay in shape,” her boyfriend explains, “and it is simply because the Latino community, when it comes to food. . . .” He need not finish his sentence because the camera does it for him, immediately cutting to Sylvia in sweat pants, approaching a food truck parked in an urban environment from which she purchases a dish made of corn, butter, cheese, and mayonnaise.

[2] The panel of Swan experts who are watching this footage on a television monitor in a mansion-like set, turn to each other laughing. “Something tells me those desserts and Latin foods won’t be on the menu at the Swan program,” says the host. In addition to losing 30 pounds, Sylvia’s conversion from ugly duckling to swan requires that she undergo multiple cosmetic procedures that address what her surgeon terms “bland bone structure.” She needs a chin implant and cheekbone lifts, as well as extensive lipo-suction in seven areas of her body to give her a “more feminine look.” Veneers on all of Sylvia’s teeth will “make her mouth look a little smaller.” All of this and some psychotherapy addressing Sylvia’s reluctance to trust authority figures, in general, and men in, particular, will bring about Sylvia’s full transformation, making her “pageant worthy” in three months time.

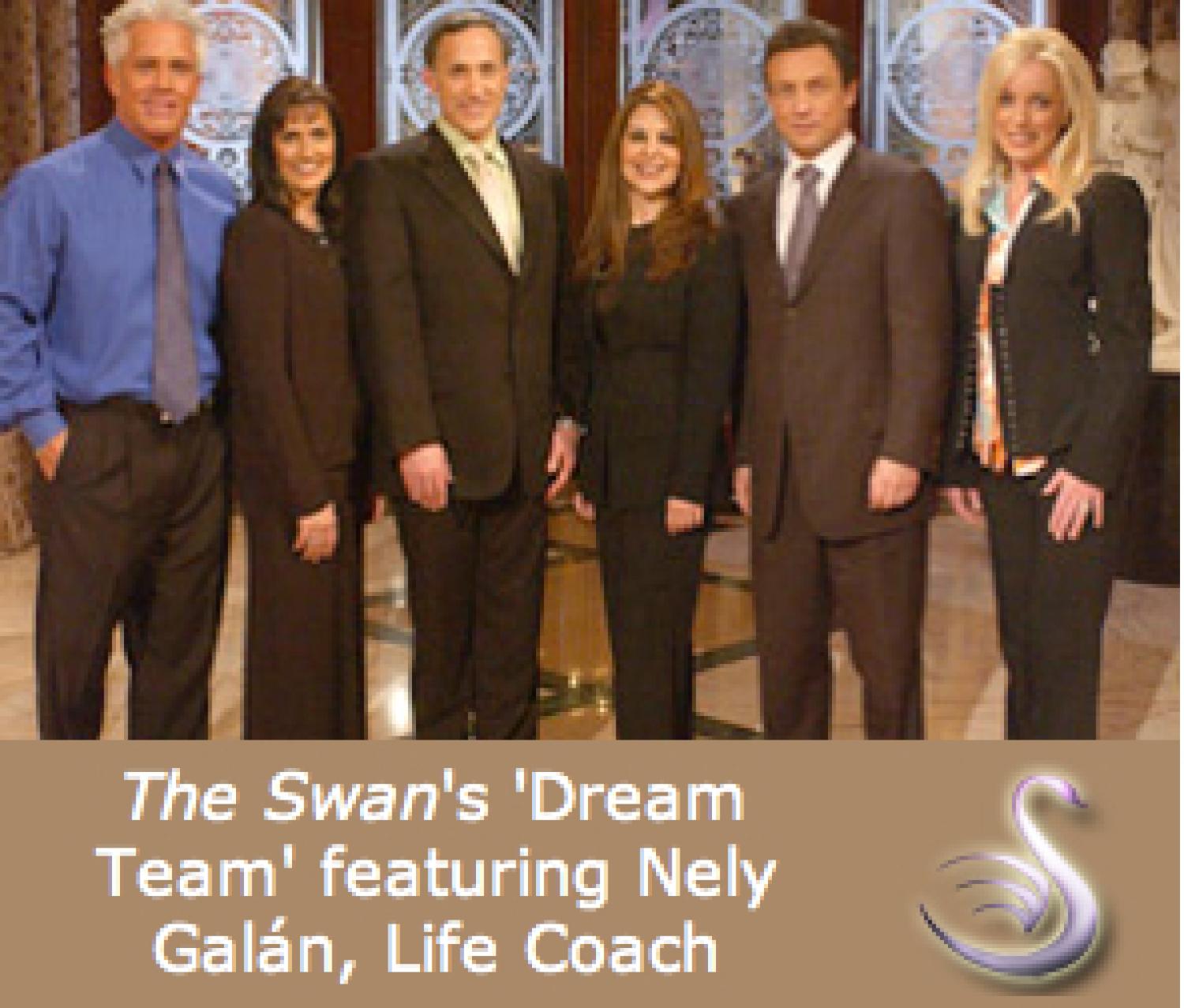

[3] Those three months are filled with what The Swan terms a “grueling curriculum” of pain, isolation, sacrifice, and temptation. Though Sylvia struggles, she – like all of The Swan’s contestants – sheds her “ugly duckling” appearance and ego, emerging for her reveal ceremony as a beautiful Swan. When Sylvia enters the Swan mansion for her big reveal dressed in a long formal gown, full make-up, hair extensions, false eye lashes, and four-inch heels, her metamorphosis draws gasps from the Swan experts, called the Dream Team (figure 1). Throughout the narrative told by the show, Sylvia has confessed her failings, undergone trials, learned to submit to a higher authority, and now possesses a face and body that mark her as not only beautiful but, in the words of The Swan’s creator, producer, and life coach Nely Galán, “resurrected,” “transcendent,” and “powerful” (Wegenstein). Though Nely’s words code Sylvia’s makeover as a spiritual experience, the altered materiality of Sylvia’s body is what allows for her legitimate entrance to the elite white spaces of the Swan mansion. She is no longer a woman whose body makes her ethnic and class excesses visible; indeed, before she can be a transcendent Swan, the Latin food she has consumed must quite literally be sucked from her body. Posing in her sequined gown amidst the opulence of chandeliers and marble staircases, we get the sense that Sylvia had to lose her fondness for eating fattening “ethnic” food from a truck as much as she needed to “feminize” her body, refine her nose, and pin back her ears.

[4] We begin with Sylvia because her story so fully expresses the race and class-centered story of shame, surrender, and salvation told by The Swan. Sylvia’s experience illustrates a logic whereby makeover renewals require a conversion that produces a conventionally gendered woman for whom other signifiers of identity, such as race, class, and ethnicity, are still present but have been subordinated to an image representing what the show calls “gorgeous womanhood.” If we consider that those targeted for Swanly renovations are, like Sylvia, coded as “ugly ducklings,” whose poor choices, ethnic excess, and downward mobility stem from their appearance, then we begin to see how The Swan illustrates the complex relationships between gender, race, ethnicity, and class at work in the making of the beautiful image, all sutured together through a religious framework that draws heavily from Christian, Buddhist, new-age, and self-help spiritual rhetorics.

[5] Since such miraculous conversions often require the diminishment of bodily markers indicating “non-normative” iterations of race and class, then we must conclude that the transcendent empowerment offered women on The Swan is presumed to exist in an unmarked category, where race and class factors invisibly contribute to social identity location. As scholars who work in critical race studies have theorized, such reasoning that claims the unmarked as the natural and normative is frequently dedicated to the production of a middle-class whiteness, here transmitted through the transformation rhetoric that fuels Galán’s mediated makeovers, so that, as Thomas DiPiero, explains, “whiteness produces itself as an apparently empty category” (105, see also Roediger, Negra). The invisibility of the normative, Roland Barthes has told us in The Mythologies, is also a critical element of the function and performance of the bourgeoisie, through which the process of representation “completely disappears” as an “ideological fact” (138). Thus, “bourgeois norms” are both referenced and experienced “as the evident laws of a natural order—the further the bourgeois class propagates its representations, the more naturalized they become” (140). On The Swan, such classed and raced values are coded through image, so that passing requires not cultural or knowledge capital but semiotic signification. Such reliance on the image, in turn transforms conventional ways of inscribing and interpreting race, ethnicity, and class, since what is valued in the made-over woman are signifiers that connote middle-class discipline (restrained forms of emotional and embodied excess), while surrounded by and clad in upper-class accoutrement (gowns, chauffeurs, tuxedo-clad doormen, Romantic paintings, mansions).

Figure 1

[6] The degree to which this classed and raced image evokes elements of the religious is critical. In her Theory of the Image, for instance, Ann Kibbey has suggested that modern capitalism as we presently experience it relies on an historical provenance indebted to Calvin as much as to Marx. Protestant iconoclasm, she argues, resisted “false images, not all images” (10). In the representation of the human body, contends Kibbey, there is both a “living human being” and “representational image,” thus establishing a logic of conversion that enables something new to materialize that did not previously exist: “[Y]ou have become something that you were not before, even though you remain physically the same person” (15). Such a logic, she notes, “converts the ordinary person or object into something that is retrospectively perceived as inadequate,” in turn heightening the salvational powers of the intercessionary agent (15). The gendered implications of this logic are profound, says Kibbey, since the sum of womanhood has often been linked to the image, which, in turn, posits the converted woman as she who is “filled by a new kind of spiritual presence, image-ness itself” (40).

[7] So, we see that class and race-based messages about the image are communicated through a discourse of religiosity, all of which naturalize the woman’s transformation from ugly duckling to swan. Much like its creator Galán,The Swan speaks in redemptive discourses that blend free choice, consumerism, individualism, personal empowerment, and spiritualism that have recently been understood as motivations for cosmetic surgery, beauty pageantry, and image makeovers (Covino, Pitts, Tice “Queens,” Bhaskaran, Banet-Weiser). BecauseThe Swan gives its contestants a very real form of cultural currency, we do not dismiss the program here as simply a tool for female objectification or racial assimilation. Instead, we argue that in its creation of a very specific woman-centered theology, The Swan opens a space where the constitution of female power and identity are problematized. While The Swan offers a very limited model of female empowerment in its reliance on physical beauty and its treatment of race, ethnicity, and class, it also allows for a distinctive form of female subjectivity that is made manifest through the signifying power of the body.

The Swan in Context

[8] The Swan is one of nearly 150 makeover programs that have flooded expanded U.S. cable since 2000, participating in what Rachel Moseley has described in Britain as a “makeover takeover” that is equaled, if not bettered, in the United States. Makeovers dominate reality programming for complex reasons that include an aging baby boomer population eager to see stories about recaptured youth and the exigencies of reality TV production that have put an onus on non-unionized workers and non-fiction formats (factors of some significance in the wake of the Writers Guild of America strikes in 1998 and 2007-8). Though TV makeovers draw upon multiple ideological rationales to validate their transformations – from neoliberalism to American individualism to postfeminism – we focus specifically in this article on discourses of race, class, and religion that work as a motivating justification for change, using The Swan as an important test case to map a logic that is manifest across the larger genre.

[9] There are other Reality TV makeovers that engage in plastic surgery (Extreme Makeover, I Want a Famous Face, Miami Slice, Dr. 90210, Brand New You), that bring about change through weight loss (The Biggest Loser, The Craze, National Body Challenge), or that require subjects to undergo therapeutic counseling (Starting Over, Maxed Out). There are also other makeover shows that build beauty pageants into their renovation systems (Instant Beauty Pageant, Mo’Nique’s F.A.T. Chance). But since the combined surge of reality TV and makeover programming began, no show has managed to combine all of these elements except for The Swan. This, in itself, may be a dubious claim to fame, particularly since the actual air dates of The Swan were somewhat short lived – two seasons in 2004, the first March through April, the second October through December. And yet, as one indication of its popular imprint, at the time of its airing in 2004, The Swan made repeated news in national newspapers and entertainment magazines, includingUSA Today and People (a form of recognition shared by very few reality programs).

[10] The Swan continues as a media touchstone, since it is still broadcast, talked about, referenced, and parodied. The show is a highly successful export commodity (it was sold to more than 50 international media markets), redistribution (it airs in the U.S. on Fox Reality and the Style network), product (both boxed sets of the television and the spin-off book, The Swan Curriculum,are available for sale online and in stores), and social phenomenon (in addition to the reality celebrity that enabled participants to become models, television personalities, and cover girls, The Swan’s experts and style gurus appear across the makeover canon, including on such shows as 10 Years Younger and How Do I Look?. As we will note, message boards still discussed The Swan’s “radical transformations” some three years after its cancellation. Indeed, as of this writing, Nely Galán, The Swan’s creator, producer, and life coach, is developingThe New You, a television-cum-web program that reunites The Swan’s surgeons and coaches to revitalize women who are “just looking for a miracle.” Galán was also one of the participants in NBC’s Celebrity Apprentice (2008), her personal currency having appreciated due to The Swan’s cachet. A further sign of The Swan’s continuing media footprint is The Today Show’s (NBC) 2006-2007 featuring of Galán’s The New You, complete with testimonials to the values of shocking transformations that refer to The Swan as a touchstone and originary text. Indeed, Galan’s website indicates that The Swan’s dream team will live again in The New You when it broadcasts on NBC.

[11] It is not just The Swan’s omnipresence but its ideological structure and cultural relevance, we argue here, that make it a text worthy of scholarly attention. This particular makeover/pageant show has been referenced widely in other recent analyses that discuss postfeminism, makeovers, governmentality, pageantry, and consumerism (Banet-Weiser and Portwood-Stacer, Roof, Deery, Weber “Makeover,” Poster, Zylinska, Heller The Great, Makeover). These analyses speak to the richness of The Swan as a cultural text, and yet they do not fully get at the heart of its psycho-spiritual redemptive authority or the manner in which it subordinates non-normative iterations of race, class, and ethnicity in the creation of “appropriately” gendered women. The Swan does so in the context of a contemporary cultural landscape in which, as James Beckford notes, “variants on ideas of spiritual and religious liberation have seeped into sundry spheres of life” (138). In fact, a number of scholars have traced the ways that popular and media culture have blurred the traditional boundaries between the sacred and the secular, material and spiritual, body and soul (Lowney, Motley, Lofton, Smith-Shomade, Egan and Papson), in some cases noting how Evangelicals have embraced spiritualized body-centered makeovers to help Christian woman uplift their sagging spirits and bust lines (Tice “Looking”). Such emphases on faith-based consumerism take place against a cultural backdrop where companies are increasingly catering to the buying power of the Evangelical dollar with such niche products as Grapes of Galilee wine and “thongs of praise” (underwear with an image of the Madonna and child). The phenomenon of religion-as-retail has been widely reported (and mocked), with articles in theLondon Daily Telegraph (Petre) the Denver Post (Draper) and syndicated in News of the Weird (Shepherd).The Swan thus takes place within a larger secular/spiritual context, where the discourses of religion often work to validate consumerism. In the case of The Swan, consumers/subjects are asked not only to authenticate the output of money involved in extensive plastic surgery, individualized life coaching, and four-months of residence in high-end resort hotels, but to “buy” the ideological imperatives of shame, surrender, and salvation necessary to achieve an amalgamated spiritual/secular end.

[12] Television makeovers more specifically – whether of body or home, kids or dogs – function as an insistent mediated site for the manufacture and display of such typically religious experiences as spiritual crisis, shame, penitence, surrender, worship, and transcendence. They offer a modality for improvement through conspicuous consumption, a protected zone of care and critique, bordered by a strict governing structure of rules and authoritative edicts. The makeover as theme has strong antecedents in both literary and religious texts as well as in women’s advice literature and beauty magazines. The reality TV makeover similarly offers a place of redemption in the name of coherent gender identity, race and class signification, and self-improvement. A critical mass of programming now airs across global televised networks, each show offering modes of salvation that are predicated on class-specific principles of good consumerism and care of the self that offer the gateway to promised everlasting happiness. So, for instance, on Brand New You, a British makeover program that sends eight white women to Hollywood so that they might receive plastic surgery, opening credits depict hands pressed together in prayer, juxtaposed against a pale blue sky. As music swells to indicate the onset of the show, the palms separate to release an illuminated white dove that iconographically evokes spiritual release through embodied change.

[13] Other programs pick up (and drop) religion as a motivating principle for the makeover as needed to validate the transformation regimes they offer. Across the makeover canon, shows invoke a logic of necessary renewal made available to those who have suffered and now desire salvation, a motif of merit and intercession seen from Extreme Makeover: Home Edition to Deserving Design.The Swan is noteworthy in the ways that it employs notions of revival, blends secular and spiritual transformation, and utilizes psychotherapeutic frameworks to advance its goal of a feminine/female transcendence that exists free of race, ethnic, and class information. We look specifically at the logics that mark the Swan makeover/pageant conversion regime as a redemptive and racialized enterprise of humiliation, trial, conversion, and triumph. This, in turn, reinforces larger U.S. mobility narratives where self-enterprise, individual responsibility, and the Protestant work ethic are thought to yield both heavenly salvation and worldly fulfillment while overcoming barriers erected by race and/or class oppression. OnThe Swan, spiritual and secular logics fuse to create a salvation that is marked by achieving a “knock-dead gorgeousness,” where pre-makeover signifiers of race, class, and ethnicity must be refashioned in order to claim one’s “authentic” identity.

Body-Based Shame: “I feel completely unbearably disgusted with myself.”

[14] The opening segment of each episode on The Swan makes clear that dynamics of shame and surrender are mandatory for those women who will undergo the Swan program. More tacit is the suggestion that shame can only be eradicated when “ugly ducklings” submit to transforming race and class markers. On this show we therefore see evidence of television extending what Sandra Bartky has identified as “pedagogies of shame” that create “the necessity for hiding and concealment” (228). Shame itself is a common trope of the surveillance-oriented nature of reality TV (Palmer Discipline, “On Our Best,” “Video,” Andrejevic, Johnson-Woods). Since The Swan’s goal is to increase empowerment though an “improved” embodiment of the female subject, and since this enhancement is intricately tied to normalized codes of femininity, race, class, and ethnicity, these shaming rituals function as a critical factor in the show’s creation of gendered transcendence.

[15] As evidenced in the case of Sylvia, all Swan participants begin their segments of the show before a mirror, cataloging the body flaws that have handicapped their emotional well-being through self-hate, failed heterosexual relationships, and neglect. Their personal narratives underscore an injustice whose root cause is failed beauty and the consequent class and gender-shame perceived ugliness brings. The Swan’smessage underscores that to establish a beautiful somatic/spiritual interiority, the policing of the shameful body in the name of normalcy is crucial. So as we saw, Sylvia must forego eating Latin food from a truck in order to be transformed, whereas other Swan participants explicitly marked pre-makeover as raced or working class must learn middle-class codes of discipline and refinement (angry African-American Kim learns to forgive, timid Native American Merline learns to be assertive).

[16] Galán, herself, is an interesting case study in ethnic assimilation, a fact made most telling in her self-help book The Swan Curriculum. “I was twenty-three with a perm, gapped teeth, and a Frida Kahlo unibrow,” she confesses (np). But after a “boob lift,” lipo-suction, a nose job, and extensive therapy and life coaching, she considers herself attractive, a fact validated, she notes, by being listed as one of People Magazine’s“most beautiful people” (significantly, not People’s Hispanic edition). Though the color of her skin did not change, the markers of ethnicity on her body did. Historically, as Elizabeth Haiken notes, plastic surgery has been consistently used so that “immigrants and members of less-favored ethnic groups” can claim the ability to alter their identification as “something ‘other’ than the Anglo-Saxon American standard” (182). In a 2004 interview, Galán proudly claimed her Cuban heritage, and announced, “my mission is to tell the story of Latin people in the U.S.” (“Swan Creator”). When only 5% of applicants to the first season of The Swan were Latina, Galán actively worked to recruit greater diversity, going to Spanish radio stations and placing ads in Spanish-language papers (Case). And yet, such commitments to ethnic diversity wavered in 2006-7 when during pre-production for The New You, Galán said that after The Swan, “I realized that the first half of my career, dedicated to producing shows for the Latino market, was probably over. The second half of my career would be devoted to helping women stay well, live longer and feel beautiful” (Carrison). Though such goals do not automatically exclude ethnicity, Galán’s remarks suggest that ethnicity served a limited function. Situated in her own Hollywood mansion and now called a “media tycoon,” Galán’s professional success seemingly allows ethnicity to take a back seat to her transcendent identity as a beautiful and successful woman.

[17] Indeed, although social identity locations, like race and class, are critical to selecting those who will participate on The Swan, race and class move into positions of secondary importance through the processes of the makeover. So, for instance, The Swan identifies Sylvia as Latina, but the particular Latin culture Sylvia comes from is less important to the show than the fact of its high-calorie dishes, which are represented in the fat deposits on Sylvia’s thighs, stomach, and buttocks. Throughout the run of the show, almost a third of the participants were marked as “non-white.” Most, like Sylvia, were generically termed Latina. We learn that Cristina is an Equadorian-national, yet the more salient part of her story is that pre-makeover, she can only get a job cleaning offices. At her reveal, she thanks God for her transformation and says, “I came for the American dream like so many Latinas do.” In a follow-up People profile three months later, Cristina works as an office administrator who perceives herself as beautiful (Green and Lipton, 59). As indicated here, absorption into the American dream involves assimilation into a beauty culture that enables Cristina the psychic and somatic freedom to participate in American-style meritocracy.

[18] This access to meritocratic upward mobility in no way exempts The Swanfrom the way it imagines beauty as marked by both whiteness and affluence, but it does give fuller credibility to Swan contestants who, regardless of race, ethnicity, or class status, seek the extreme transformations offered through the Swan program as a way of transcending their body-based shame. As Kathy Peiss’s work on the social history of beauty culture has shown, though the cosmetics industry is never “far removed from the fact of white supremacy,” make-up itself has allowed individual women, regardless of race or class, the opportunity to assert “their right to self-creation through the ‘makeover’ of self-image” (203, 6). Though The Swan offers a far more radicalized transformation than that discussed by Peiss, the dual possibilities for both self-creation and submission are mutually possible in The Swan’s logics. Beauty, then, serves as an intermediary currency that buys Swan participants the appearance of upward mobility.

[19] This effacement of specific race and class discourses, however, does not eliminate the ways in which the “aesthetic face,” as Anne Balsamo puts it, “symbolizes a desire for standardized images of Caucasian beauty” (212), a fact graphically underscored when The Swan explicitly labels the bumps and bulges on Sylvia’s body as a consequence of her vague ethnic origin. Indeed, although all of The Swan’s contestants save one “need” liposuction, it’s only in the case of “those who have ethnic skins” that excesses are attributed to cultural/ethnic factors rather than simply “bad” habits. Surgery does not, of course, erase Sylvia’s ethnicity. She is still as fully – and as ambiguously – Latina as she was before the operation. But surgery and the entire makeover induced by the Swan program brings Sylvia more fully into a culturally constructed version of appearance that subordinates race and class concerns to an iteration of gender that is resolutely whitened and not working class. Though scholars such as Maxine Craig, Ruth Holliday and Jacqueline Sanchez Taylor argue that in a broader sociological world there is no singular version of beauty, particularly for women of color, The Swan tells a different story, offering a mediated example of what Herman Gray calls an “assimilationist discourse of invisibility” that, in its refusal to allow for difference, creates a world premised on “color blindness, similarity, and universal harmony” (85). The consequence of such assimilationist narratives, Gray notes, is that race becomes situated as a factor of individual experience whereby “the individual ego [constitutes] the site of social change and transformation” (85). This, in turn, privileges a “subject position . . .necessarily that of the white middle class” where “whiteness is the privileged yet unnamed place from which to see and make sense of the world” (86). Within this regime gender normalcy is coded as white, an amalgam of middle and upper classes, heterosexually desirable, confident, and well-adjusted. The surface logic of the program collapses racial and class diversity into emotional and psychological hardship, thus suggesting that the wounds of a racist or classist culture can be healed through the balm of beauty.

Figure 2

[20] Regardless of social identity factors, then, The Swan suggests that the ontological category called (ugly) woman necessitates radical transformation in the name of gender conformance. The narrative and visual presentations are punctuated with video clips that substantiate this need. As we meet each new Swan contestant, we see drained and depressed women dressed in baggy clothes who speak of their deep unhappiness. Many of the women are described as hyper-masculine or manlike, as in the case of Cindy and Marsha who are “shameful shavers.” Surgeons report that Rachel and DeLisa (both of whom win the pageant in their respective seasons) have blocky bodies that need feminizing. In tandem with gender and class shame, we see emotional despair: Kelly was isolated and spit on by the other children; Dawn’s father rejected her; Tanya hides from people. Shame is the common denominator binding these women, a shame that has written itself on their bodies, shaped their psyches, and marked supplicants as needing redemption. Significantly, pre-madeover women are not depicted as out-of-control and hyper-sexualized, as on other reality TV fare. Instead, they are dutiful but dowdy: hardworking, responsible, and morose women whose shame is a matter of internalized social sanction rather than deliberate transgression. In this regard, improving Swan candidates’ class position is equated with creating a beautiful body that can interrupt what the show implies are superficial factors, such as poverty or familial heritage, that lead to bad teeth, an uneven complexion, or cellulite-riddled thighs. Significantly, spiritual riches are here evoked through material rewards.

[21] On-screen imagery further emphasizes this point. Through the large frame of the mansion’s state-of-the art projection system, confessions from Swan hopefuls are offered via videotape from their tattered living rooms or crowded bedrooms. Though their appeals speak to a desire to alleviate their body-based shame, there is also a class-based appeal at work, suggesting that their appearance has blocked full participation in a meritocratic economy, which has, in turn, hampered their spiritual development. As if to emphasize the rewards a beautiful body will bring, The Swan visually contrasts the contestants’ modest home spaces with repeated images of opulence, including an establishing shot of an enormous mansion seemingly in Hollywood. From the marble foyer to the gilded stair railings to the Romantic paintings in heavy frames on the wall, this is a scene depicting luxury and expense, in turn suggesting the link between material and spiritual rewards.

[22] Throughout the program, these semiotic markers of class status are emphasized, even as the bodily signs of makeover subjects’ working-class lives, what Vivyan Adair calls “the not so hidden injuries of class,” are reversed (28). The program suggests that image in itself will assure a woman’s entrance to such rarified places as the Swan mansion. Participants do not, for instance, need to learn other “lady-like” competencies such as proper etiquette, social conversation, or table manners, as do women on such reality TV programs asLadette to Lady, American Princess, or Australian Princess. Instead, they must only look the part to earn their reward. Race and ethnicity are equally germane to this logic of access and ascension since only those who satisfy a “whitened,” assimilated image are allowed within the mansion, meaning that all of the ugly ducklings, whether identified as Caucasian, Hispanic or African-American, require the Swan’s ritual blanching as part of their makeover. Here it is important to note that whiteness on The Swan is less about skin color than appearance. Mirroring what Elizabeth Haiken has analyzed about race and ethnicity at the turn of the twentieth century, at the Swan mansion whiteness is defined as an absence of identifiable racial markers, as well as any class markers that might constitute a “significant deviation from the average” (Haiken, 181). For more on how cosmetic surgery has been deployed to alter racial and ethnic markings, see Kaw, Banales, and Gilman). Whiteness, in this sense, operates as the unmarked. And significantly, The Swan’s bodily renovations create a classed whiteness fit for Hollywood mansions, not suburbs or trailer parks.

The Shame of the Ordinary: “A self-confessed average girl.”

[23] As we’ve observed, though The Swan specifically targets and labels “women of color” for its rejuvenations, women coded as white are in equal need of a makeover. The value The Swan places on gorgeous womanhood cannot tolerate what it derides as average, a fact underscored when Caucasian Rachel is described as “a self-confessed average girl.” Women in real life and on makeover shows often claim that their decision to seek out plastic surgery is not predicated on being beautiful but on being normal, yet there is a very clear bias on The Swan against those bodies that signify as average. Consider, for instance, the surgeon’s statement that starts every show: “Our goal is to transform average women into confident beauties.” His words set up a binary, making it impossible, according to the logic established by the narrative, for “average” women to be either confident or beautiful. His statement also suggests that beauty and confidence are inter-changeable terms, so there can be no insecure but good-looking woman. Individual episodes underscore this same reasoning. For instance, Rachel confides, “I feel average because when I look in the mirror, that’s what I see.” On another episode, Caucasian Sarina confesses, “I’m just OK. I’m not ugly. I’m not pretty. I’m just kinda there. When I look in the mirror, I see the ‘ultimate Plain Jane.'”

[24] The shame of averageness is hardly exclusive to Rachel or Sarina. Throughout each episode there is a very clear sense that to be ordinary rightfully contributes to feelings of isolation and deep unhappiness. The discourse of averageness sets up a clear division. On the “bad” side are a number of co-related terms: ugliness, ordinariness, and blandness that lead to being ignored, which is coded as undesirable and unworthy. On the “good” side there is seemingly one signifier: beauty, and as we have demonstrated thus far, beauty is connotatively linked to gender normativity that articulates through race and class codings. Beauty, in turn, leads to the most precious of all signifiers: success, happiness, love, confidence, appreciation, power, and somatic and spiritual transcendence.

[25] Given the homogeneity of beauty as a signifier, it makes sense that the pluralism represented by the “before” version of the women is almost entirely obliterated in “after” images. Not only are “imperfect” bumps and bulges refined, but so are most markers of class, race, and ethnicity. So, for instance, African-American Kim loses her cornrows for long straight silky hair, and Native American Merline, who cannot afford dentistry, is given a million-dollar smile. The quest to make these women seem less average requires that “conventional” beauty be the exclusive signifier. Even those women clearly marked as white and/or middle class, such as police officer Cinnamon, must transform from dull to luminous, losing her brown curly shoulder-length hair for shiny platinum blonde extensions. It’s not a subtle process. One sense of the popular reaction to The Swan’s transformations came from the actress Susan Sarandon, who observed, “I saw a commercial for The Swan, a before and after makeover show, and the woman in it had a particularly ethnic face; but in the ‘after’ she ended up looking like a female impersonator, and that’s horrible” (“Sarandon Speaks,” 200).

[26] Indeed, the whitening effects meant to further a race and class-specific version of hyper-femininity were still being discussed at least three years afterThe Swan originally aired, as evident in a 2007 snopes.com conversation thread titled, “There are no ugly women, only poor women” (figure 2). Many postings, like one from BringTheNoise, comment on The Swan’s post-makeover appearances as artificial and approximating, “generic Hollywood wannabes” (3/16/07). In response, trollface notes, “Want to know what I think is the most horrible and insidious part of their plasticizing? Look at the comparative skin colors of Cindy Ingle and Christina Tyree. Don’t they look awfully white in the “after” pics? I don’t care whether it’s due to skin-bleaching, make up or retouching the photo afterwards, I think it says something very, very bad about a society where the lightness of skin is an indicator of ‘beauty'” (3/19/07).

[27] Internet conversation boards such as this suggest that viewers may be highly resistant to the salvation-through-surgery messages that The Swanespouses. And yet, The Swan’s insistence on a particular kind of surgical beauty potentially offers a complicated outcome made manifest through the ambiguous difference between what is average and what is normal. Scholars such as Kathy Davis have argued, for instance, that plastic surgery is capable of intervening at the level of identity, rather than simply of appearance, because it makes women “become ordinary and normal – ‘just like everyone else'” (Dubious 98). Both Debra Gimlin and Victoria Pitts-Taylor further suggest that plastic surgery plays a critical role in identity formation in the way it enables the surgery recipient to align the body with an inner sense of self. Gimlin reflects, “I believe that women who have plastic surgery are not necessarily doing so in order to become beautiful or to please particular individuals. Instead they are responding to highly restrictive notions of normality and the ‘normal’ self, notions that neither apply to the population at large (in fact, quite the reverse) nor leave space for ethnic variation” (96). (For more on feminist responses to plastic surgery, see Balsamo, Blum, Chapkis, Covino, Davis Reshaping, Fraser, Frost, Morgan, Weber “Beauty,” Wolf). Popular message boards, like that on snopes.com, evidence a non-scholarly investment in these same debates. In this discussion stream, for instance, of 96 responses, 63 used The Swan to debate matters of what constitutes naturalness, including whether or not make-up, hair color, surgery, or even tattoos produced results so artificial that they were “cheating.”

[28] Both academic and popular responses thus indicate the very schism between the normal and the normative that functions as the epistemological cornerstone for shame on The Swan. At stake is not what actually exists pre makeover, or what might exist post transformation, but what participants believeshouldexist. This is the terrain of the imaginary. The Swan plays a role in feeding this imaginary by suggesting that normativity is keyed to the extraordinary, a location relentlessly coded as a whitened, middle- to upper-class, and ratified by the adoring gaze. Though The Swan candidates’ pre-made-over wrinkles and cellulite as well as their bodily anxieties make them far more normal than do their post-makeover runway-ready bodies, the stigma that The Swan places on the “average girl” compels her to desire the normative over the normal. We see a situation, then, where the defining power of what constitutes the norm, as Michel Foucault suggested, not only establishes the normal but regulates and makes intelligible the aberrant, here coded as dowdy and visibly classed or raced. On The Swan, the values of the norm jettison subjects into the exceptional “gorgeous woman,” offering an outcome not about fitting in with others but in surpassing them. The ugly duckling who has desired to become normal achieves her goal by transcending the imaginary exemplum of every-woman. As Rachel Moseley notes about makeover shows more broadly, “These are, precisely, instances of powerful, spectacular ‘über-ordinariness'” (314). The made-over subject becomes the quintessential representative of the extra-ordinary, a category of the unmarked that functions as the idealized signifier of a whitened and upwardly-mobile subject. The post-makeover woman exists in an ethnically anonymous state where it is her beauty, rather than her racial, ethnic, or class features, that code her identity.

Surrender: “She surrendered to her transformation inside and out.”

[29] Before a transforming Swan can bask in her moment of transcendence at the pageant, she must fully surrender to the Swan regime. Thus, after the show establishes its participants’ shame, it moves to its narrative heart where makeover subjects are continually reminded of both the sacrifice expected of them and the imperative to surrender in order to achieve the salvation that is promised by the Swan pageant. The Swan functions on the premise that only complete capitulation will achieve totalizing bliss, repeating elements of the conversion trope that require what Hans Mol identifies as a “re-ordering of priorities and values” that often compels the convert to repeat “over and over again how evil, or disconsolate, or inadequate he [sic] was before the conversion took place” (53). The intra-episode repetitions of subjects’ bodily and psychic shames, then, serve to underscore and strengthen their new faith in the Swan regime. By looking more closely at the mechanisms for encouraging Swan contestants to sacrifice and surrender, specifically the doctor/patient relationship, Galán’s mentoring and spiritual goals, and the therapeutic inspiration Swan contestants experience, we further demonstrate a complicated power dynamic riddled with messages about gender, race, and class.

[30] Galán has described her version of surrender as not giving over “to someone else’s vision of what you should look like. I think surrendering is . . . being the best you can be inside and out” (Wegenstein). She attributes Rachel’s successful transformation and ultimate crowning at the beauty pageant to her willingness to surrender:

Rachel simply surrendered to her path. Rachel came ready to change. She surrendered to finding her “aha” moment. One of the big issues on the show is control. Surrender and control, which is the hardest thing people have. Sometimes you have to surrender to experts, sometimes to God. You have to surrender. And for people who are control freaks, it’s very hard. (Wegenstein)

The Swan’s creator here uses the language of spiritual surrender to legitimateThe Swan’s demand that acolytes relinquish personal control in order to gain transcendent womanhood.

[31] The gendered power dynamics of the surrender mandated by the Swan regime are particularly evident when female contestants interact with their male surgeons. Each patient undergoes multiple surgeries, yet the physical feat is depicted as a triumph not for the patient but for her doctors, a process that puts on display the multiple power inequities between doctor and patient along gendered, raced, and classed lines, as well as the power differentials of education, expertise, and status. Scenes in which the doctors talk about the processes invariably suggest that performing the procedures require extraordinary skill, whereas enduring the surgeries requires only obedience, discipline, and surrender. Surgeon Terry Dubrow, for instance, characterizes Gina D’s surgery as “the hardest nose I’ve ever done. In fact, this is the hardest operation I’ve ever done.” The severity of the “problem” for all of the Swan contestants serves to underscore the idea that failing to invest in beauty invariably leads to both a health and a spiritual crisis. In creating this logic, The Swan establishes a virtual fear economy where beauty constitutes a necessity more dire than clothing children or putting food on the table. As the host says about another Swan hopeful, “Andrea learns there is a high price to pay for neglecting her teeth.” Given these pronouncements, it’s no wonder that many ofThe Swan’s contestants are scared straight into surrendering their psyches and bodies to the treatment of the Swan experts. Though as Suzanne Fraser has demonstrated, actual doctor/patient relationships engage in a far more nuanced power dynamic, The Swan’s representation underscores binaries in which authority and submission are both totalized and naturalized. Indeed, just as in more traditional religious structures, it is the perceived stability of these power relations that lead swans to their salvation.

[32] In its combination of weight loss, life coaching, and therapeutic change, The Swan ups the ante on the suffering that subjects must endure in order to claim “gorgeous womanhood.” Further, the sorts of mediated power dynamics The Swan projects, where all-knowing authorities supervise the labors of those beneath them through a combination of coercion and care, enacts not just a godly metaphor but a labor paradigm of boss and worker. The represented power inequity between makeover subjects and experts serves to reinforce the naturalness of their differences, offering yet further evidence of The Swan’s re-enactment of the power differentials that accrue around race and class difference. Contestants must continually learn to trust expertise and follow the rules, to give themselves over fully to the Swan program, and to invest in and reify the authority that accrues to the Dream Team, which is collectively coded as white, educated, and elite. These lessons are not depicted as coming easily for Swan candidates. Though each participant is joyfully grateful for the experience to undergo extreme transformation, there is plenty of backsliding and recalcitrance. We are shown subjects who sneak full-fat yogurt or who willfully refuse to wear their chinstraps. As with most makeover shows, giving textual time to resistance moments emphasizes narrative tension and reinforces the rightness of the power balance so that those in a position of expertise coach and compel, while those needing help must learn to relinquish their resistance.

[33] During these times of tribulation and struggle, the producer and life coach preaches her version of tough love. “From this moment on,” Galán tells one participant, “you have to think military.” Her admonition is intercut with a similar message from the personal trainer. “This is a “24/7 commitment.” Over and over, the experts underscore the rigor of this program, as does the voiceover narrator, who asks about each candidate, “Is she tough enough to endure the Swan program?” The implication is clear: transformation is not an easy process. It requires suffering, sacrifice, fortitude, and a complete sublimation of the ego. The subjects’ only salvation in the face of such adversity is to trust and obey their advisors. Indeed, the more contestants surrender to experts, the more likely they are to “win” the particular episode and be rewarded with participation in the pageant. Galán doesn’t mince words when speaking about the importance of obedience to (her) authority. “I’m really happy with Sylvia’s result because she worked really hard, she has a great personality, and she surrendered to the program.”

[34] Within the conversion process, Galán is a significant agent of both authority and affection. She can be a tough advocate, but she also functions as a comforting and soothing confidante, often reassuring Swan participants that she empathizes with their pain. Galán has publicly credited her success in the entertainment industry with the mentoring she has received – the same mentoring that she purports to offer the Swan participants. Her role models, she explains, have helped her bridle her “incredible passions.” “People told me not to do certain things and I didn’t listen. Now when my mentors tell me something, I listen” (Oldenberg 3D). Surrender, in Nely’s opinion, is not a form of disempowerment. It is a clear choice to assemble experts and adhere without question to their advice. Galán’s message of surrender endorses regulation in the name self-empowerment, yet her words also reinforce stereotypes about the passionate excess of Latinas, an excess that must be curbed to achieve successful assimilation. Further, in Galán’s re-telling of her surrender-to-mentors narrative, her own agency is critical. She selected her advisors, carefully choosing whom she would approach and exerting a degree of autonomy in her choices about whose advice mattered to her. Although Swan contestants have applied to be on the program, they are disallowed a comparable degree of agency in their options for change. Indeed, they are asked to sign on to a process, to forego active monitoring of its progress, to isolate themselves from a support network of friends and family, and to allow their experiences to become media products that can be sold and distributed internationally.

[35] Therapy plays a further critical role in naturalizing the surrender demands and in reinforcing the tacit imperatives about race and class that are a part of the Swan regime. The Swan is unlike any other extensive plastic surgery show in its prioritizing of the therapeutic process as part of the overall transformation. In this regard, surgery is represented not as a replacement for therapy but as a co-facilitator of change. Galán has said that were The Swan a product fully of her design and not subject to the edicts of the Fox network, she would have made it far more about therapy than plastic surgery (Wegenstein). In an interview withHispanic Magazine, she emphasized the importance of working with feelings: “If you don’t do the inside job . . . it doesn’t matter if you get a nose job or a boob job; you’ll feel bad again” (Pliagas). The Swan’spsychologist, Lynn Ianni, is therefore depicted in each episode working with Swan contestants on their issues of childhood traumas, abandonment, betrayal, and poor self-esteem. Most have relationship problems; several struggle with low sexual desire. They have been too giving, too willing to violate their own boundaries for the sake of others. Therapy is prescribed as part of Merline’s plan, then, so that she can “learn how to tackle her insecurities and focus on herself.” The process of becoming a Swan not only involves greater surface beauty but deeper psychological resiliency and a woman’s renewed prioritization of her own needs.

[36] On the surface these goals of prioritizing women’s needs seem laudatory — even feminist — objectives, in line with several ground-breaking books, including Gloria Steinem’s Revolution From Within or bell hooks’Sisters of the Yam, which argue for the central role of self-esteem in female empowerment, cultural consciousness raising, spiritual recovery, and collective self-healing. hooks, in particular, writes of the importance of a community of faith that fuels spiritual solidarities and feminist empowerment. In response to the many critics of the show, Galán has asserted, “I never intended to make a show that was anti-women. On the contrary, it was designed to be a show that gave women a break and gave them all the possibilities and all the options to jump start their lives” (“Swan Creator”). The Swan’s approach to female empowerment, however, flattens psychological issues into one-dimensional heterosexual relationship problems. In most cases, women must learn to surrender their anger so that they might move forward, though “forward” articulates as an abstraction designating both the potential beauty pageant and a future idealized heteronormative life.

[37] To gain greater confidence in choosing men, for example, Belinda finds that she merely needs to tape pictures of former boyfriends to a punching bag and pound them several times. To overcome her trust issues, Sylvia role-plays a conversation with her father in which she tearfully says she never felt his love.The Swan’s experts note that Sylvia will have to submit to the discipline of the Swan program “before she can move on,” clearly indicating that in this case “letting go” becomes another form of surrender required for progress. Even if we dismiss the disputed validity of Ianni’s credentials, the homogenized one-size-fits all therapy that each Swan contestant receives seems de-personalizing at best and unethical at worst, since it cannot and does not account for difference. Though Ianni told USA Today, “It’s not about exploiting anybody – inside or out” (Oldenberg 3D), it’s hard to watch the psychological work being done on The Swan with its relentless focus on romance and its complete disregard of more systemic impediments to self-esteem and not believe that the show is grounded in a heterosexist belief that a woman’s greatest sense of self comes as a consequence of her relationship with a man.

[38] Similarly, as Helen Wood and Beverley Skeggs theorize about narrative confessionals on reality TV more broadly, although therapeutic moments on The Swan offer an affirmation and articulation of middles-class restraint, rationality, and verbal proficiency, these moments allow no space for the class and race-based causes of low self-esteem or needs for collective empowerment. Steinem, for example, recognized that her sense of personhood was highly inflected through an internalized class and gender-based perception of “society’sunserious estimate of all that was female” (25). She recognized that her self-esteem was influenced by growing up among “good people who were made to feel ungood by an economic class system imposed from above” and that “sexual and racial caste systems are even deeper and less in our control than class is” (21). The Swan can allow for no such complexity. Indeed, by making reference to the psyche and then minimizing its complicated constitution — including vestiges of gender, social class, and race — The Swan over-simplifies the therapeutic process, suggesting that mental health or positive self-esteem is only a punching bag away. This representation serves to cloud the power dynamics attached toThe Swan, since it claims the makeovers it performs create transcendent female empowerment, but the root causes of women’s dis-empowerment are never systemically addressed.

Salvation as Pageantry: “But in the end her sacrifice led to salvation”

[39] As we have indicated, transcendence into gorgeous womanhood involves assimilation into a beauty culture that overwrites other social identity locations. If man-like blocky bodies, shameful shaving, impoverished neglect, or ethnic excess mark the pre-madeover ugly ducklings as needing a makeover, the beauty pageants that culminate each season offer proof of each woman’s successful transformation into beautiful swans. And here too the passage from before to after is naturalized through discourses of the spiritual, as evidenced in Galán’s naming of the pageants as opportunities for “resurrection,” where the winner is, quite literally, crowned with glory (Wegenstein). The pageant, even more than the stylized reveal moments at the end of each respective episode, offers the visual evidence that, as the host says, “in the end her sacrifice led to salvation.” As we have noted, The Swan is particularly invested in obliterating the ordinary by creating post-makeover women who signify ethnic anonymity through an amalgamated middle and upper-class whiteness. Reveal ceremonies at the end of each woman’s respective episode offer high-drama events where made-over Swan participants walk across the Swan mansion’s marbled floors, awaiting their first glimpse of themselves in a large ornate mirror. Their full apotheosis, however, does not come in the “mirror moment,” but in the beauty pageant, thus suggesting that both female empowerment and spiritual enlightenment reach their full expression in display.

[40] As madeover subject Marnie walks down the runway in her negligee at the first Swan Pageant, for instance, she claims the moment as rich in female empowerment, “This is the true meaning of ‘I am woman, hear me roar!'” As a lead-in to the swimsuit competition, the host similarly informs the audience, “The real test of a woman’s confidence is how she looks in a bikini.” In behind-the-scenes footage during the second pageant, we see the swans laughing and playing with one another, giggling as they prepare dance numbers, flirting with strangers on the street as they are driven around Los Angeles in an open-air bus. As so depicted, the pageant phase enables women to claim a homosocial sisterhood seemingly free of race and class difference. This community is unavailable to them in either their ugly duckling misery or their interstitial experiences of pain and suffering. Intercut interviews showcase women tearfully grateful for their new sisterly community and inner peace. We see, then, that the language and purported goals of a second-wave feminism are here fused with spiritual well-being, the amalgam used to affirm both the outcome of the makeover and the pageant itself.

[41] Historically, the female body made vulnerable through hyper-visuality is yet one more arena where class and race privilege collude to code a white elite image as glamorous or sexy and an ethnic, raced, and working-class appearance as trashy or suggestive. Taken as such, the pageant has the potential to underscore women’s objectification through the hyper-sexualization of their bodies on display. Although we do not dispute that sexual confidence affords a significant form of currency, particularly as Holliday and Taylor note in a postfeminist rendering of female power as highly sexualized and playful, we resist the idea laid out here that a sexualized visibility is the only viable means of attaining female power. The pageant puts female bodies in public competition with one another and quantifies their “beauty, poise, and overall transformation” through external signifiers such as “high-fashion” photo shoots and run-way walks in bikinis and lingerie.

[42] Yet, Swan participants do not voice feelings of misogynistic victimization. Instead, they speak of the confidence, new opportunities, and spiritual balance that accrue to them as a result of their makeover and pageant experiences. Though we must be reminded that participant statements are carefully edited to emit producer objectives, it does seem, given the desire women have to participate in The Swan as evidenced by its more than 500,000 applications, we might be able to stake out some place where pageants function, in Sarah Banet-Weiser’s words, as a “feminist space where female identity is constructed by negotiating the contradictions of being socially constituted as ‘just’ a body while simultaneously producing oneself as an active thinking subject, indeed, a decidedly ‘liberal subject'” (The Most 24). For Galán, the pageant quite clearly participates in the making of not only the liberal subject but the transcendent female soul. She considers The Swan’s pageant a democratized event that celebrates women, precisely due to The Swan’sshowcasing of plastic beauty (for more on cosmetic surgery and beauty pageant competition globally, see Simoneta, Runkle, and Harney. For general discussion on ethnicity, race, globalization, and pageants, see Craig Ain’t I, Cohen, Wilk, and Stoeltje, Barnes, Oza, and Parameswaran). “[W]hen I see a normal pageant like Miss USA,” she told People, “it is demoralizing because I cannot aspire to that since I was not born beautiful. If I see Miss USA, I’m a short girl, I don’t feel happy watching that. If I watch The Swan and I am overweight and feeling like the pits, I am inspired because anyone can be the Swan” (Green and Lipton 60). Accordingly,The Swan purportedly offers egalitarian possibilities for ordinary and tormented women from all social locations to be “part of the flock.” The message is that all women can find hope, renewal, and redemption by adopting The Swan’s gospels of bodily recovery and surgical maintenance. If the vestiges of race and class alter in search of such redemption, then so be it.

[43] In this domain of the pageant, the sign of the unmarked body becomes the single signifier of achievement and the primary means through which to achieve salvation. In many ways, the importance of the body in The Swan contests the divide that Banet-Weiser has identified in the Miss America pageant between subject-defining elements, like interviews and talent displays that produce the woman as an “active thinking, subject,” and those other elements, like the swimsuit competition, that operate as “simple showcases for displaying objectified bodies” and mark a woman as being “just a body” (24). On The Swan, though there is a clear valorization of improved interiority that registers as good self-esteem, there is no reference point outside the body. Indeed, it is through the very act of fixating on the body that one discovers how to transcend it. Enhancement of the body frees the pageant participants to aspire not only to fashion modeling but also to role modeling. Gina B., for example, assures the pageant judges that throughout the Swan program she has struggled, surrendered, and found peace. She now realizes, “I deserve time and energy to become the best woman inside and outside. I’m worthy of attention. I am not selfish but helping myself to a more productive life and it will allow me to inspire women to embrace the swan deep inside them so they can spread their wings and fly.”

[44] Much like the religious convert, contestants believe their journeys of healing and affirmation will inspire others to choose medical surrender, redemption, and rebirth. Swan hopefuls have been granted the confidence to be visible, to have faith in one’s body, to be seen by public and private eyes without fear of censure. The body in this regard functions as the locus and limit of salvation, there being no place where the Swan is not “just a body” since a new-found inner peace requires full focus on and transformation of the body in order to access internal strength. As such, The Swan functions as a compelling mediated site where the exigencies of the mind/body split are rectified. Both Susan Bordo and Elizabeth Grosz, among others, have done much to problematize the mind/body duality that positions, in Grosz’s words, “subjectivity and personhood with the conceptual side of the opposition while relegating the body to the status of an object, outside of and distinct from consciousness” (4). Pippa Brush has observed in relation to Grosz that, “articulating the body as plastic and malleable,” as is the case in plastic surgery and makeover discourses, “makes the body seem more like an object than the location of self” (26). As Grosz elucidates, such regard for the body potentially duplicates a “mind/body dualism” by “taking the body as a kind of natural bedrock on which psychological and sociological analyses may be added as cultural overlays” (144). Though popular culture can often reinforce mind/body divisions, The Swan requires mediation of the body to achieve subjectivity and empowered femininity. It is only through the shame and suffering of the body, that a woman can achieve what The Swanposits as spiritual riches made manifest in material form: inner peace expressed through the beautiful body. Such embodied resplendence, in turn, allows the ugly-duckling-turned-Swan to transcend to a celebrated sphere where working-class and/or ethnic excess have been transubstantiated into gorgeous womanhood.

“[T]he goal is to be comfortable in your own skin, whatever it takes . . . “

[45] Classic film theory posits the woman as the object of the gaze, who in her spectacular to-be-looked-at-ness passively receives the active and affirming gaze of the looker, always coded male (Mulvey “Visual,” Berger). Many theorists have problematized this dynamic (Mulvey “Afterthoughts”), in particular seeking to account for male to-be-looked-at-ness (Neale) or female gazing (Gamman) or a queer-butch gaze (Halberstam). Kibbey offers a theory of the gaze that we see manifested in The Swan, since she suggests that the power of image and the woman’s incarnation through image-ness “paradoxically ha[s] the power to ideologically displace the material means of the production of images to herself as object” (40-41). In this respect, women potentially possess “a controlling power as the source of images” (41). Similarly, on The Swan the made-over body functions as a feminized object converted into a site of agency that is ratified by the power to command the gaze. Though The Swan does not eschew the gaze in and of itself, the economy of looking that it establishes disrupts active/passive positions between the masculinized gazer and the feminized gazed-at, suggesting that the gaze can be earned and controlled. This, in turn, allows the made-over woman to control the gaze through the power of her visuality, a form of empowerment that, it suggests, reinforces legitimacy as both a soul and a self.

[46] The Swan’s success in making this claim for an empowered to-be-looked-at-ness relies on both spiritual and secular tropes that mutually posit the shame and suffering of the body as necessary precursors to a form of transcendence that is tethered to inner peace and articulated through the worldly currencies of image and attractiveness. The entanglements for class, ethnicity, and race in The Swan’snarrative of shame, surrender, and salvation mark this makeover/pageant reality TV show as a complicated cultural text that has been called by its creator “very loving to woman,” its participants “the place of my heart and soul,” and its critics “exploitive and misogynistic.” Like many religious systems, The Swan requires that its participants be fully abject in order to be saved by the regime it offers. Since a tacit ticket for entry into the Swan program is both femaleness and a compromised sense of self, and since this lack of ego strength is predicated on an absence of beauty signification, the entire process is distinctly skewed to create a “normalized” version of femininity where race, class, and ethnicity function as secondary details. Altering each woman’s sense of her own appearance provides the antidote to her disempowerment; yet, empowerment requires that makeover subjects surrender their resistance, their autonomy, and their bodies to the Swan’s dream team.

[47] Nowhere is this more evident than in the spiritual threads woven throughout the Swan program and pageant. The reward for admitting one’s shame and perfect surrender is moving from program to pageant to media star where becoming a celebrated image coded with elite whiteness functions as a form of spectatorial salvation. This, suggests Galán, is what The Swan offers: being comfortable in one’s own skin, feeling confident in one’s body, being the center of attention. As she puts it, her message is:

[F]or all of us, particularly women . . . to find ourselves comfortable in our own skin. I think that what I intended to say with The Swan is not that you should change yourself and not like yourself and be someone else, but rather that when you hit a roadblock . . . that you look for those answers. Because the goal is to be comfortable in your own skin, whatever it takes, inside and out. (Wegenstein)

Since as we have noted, The Swan, in both program and ideology, pathologizes before-transformation diversity, it similarly camouflages the bumps and bulges, the pockmarks and deviations, that signify not only excess but failure to evoke an idealized raced and classed norm. Galán’s call for comfort in one’s own skin therefore requires that one move out of the specificity of that skin, leaving the particularities of heritage and experience behind. Though The Swan may offer woman a meaningful form of cultural capital, confining female power to surgically constructed bodies that have been de-cellulited, hyper-glamorized, and de-racinated creates a consequent ideal in which ethnic, classed, and average bodies are de-legitimated. It heightens a notion of shame-based isolation, that, as Bartky notes, can be “profoundly disempowering” (237) and turns away from a politics that is mindful of power relations and the need for connection, engagement, and community solidarities. The emphasis on individual salvation, though consistent with American valorization of autonomy, reaffirms a problematic politics in its insistence that projects of the self will circumvent structures of inequality, eliminating the need for collective action.

[48] In so doing, The Swan relies on the legitimating rhetoric of spiritual transformation to naturalize its makeover processes. The Swan gospels teach that there is empowerment, relief from censure, and transcendence in surrendering to radical transformation. Through it all, the body functions as the proof of one’s overall well-being. Women seeking salvation through the Swan curriculum can therefore expect not resurrection of the body but resurrection to a body. It is an idealized form only salient through representation, constructed and made intelligible through refined skin and bone — the flesh made image.The Swan’s contestants are represented as achieving confidence and healing, as well as “comfort in their own skin.” If the soul is at stake, as The Swan so powerfully argues, and if bereft of her image, a “woman faces [semiotic] extinction,” as Kibbey theorizes (45), a therapeutic salvation gospel of shame, surrender, and salvation might to many women be, quite literally, irresistible.

[49] Given the appeal of both its metaphorical and material messages and given both The Swan and Nely Galán’s seeming perpetual presence in the contemporary mediascape, this makeover/beauty reality TV program strikes us as a signature text, which illuminates the vexing tensions that arise between identity and ideology. It is a powerful contributor to other media and cultural texts that work to redefine and make accessible concepts of the worthy self. Though its complicated rhetorics about race and class mark The Swan as deeply problematic, these same discourses valorize and lay claim to a form of female empowerment that offers women specific cultural currency made manifest through the symbolic and material nature of the body.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dwight Billings, Greg Waller, Radhika Parameswaran, Katie Lofton, and the anonymous readers, all of whom offered invaluable feedback. We also thank Bernadette Wegenstein for so kindly offering us interview footage.

Works Cited

- 10 Years Younger. Evolution Film & Tape. 2004 – present.

- Adair, Vivyan. “Disciplined and Punished: Poor Women, Bodily Inscription, and Resistance Through Education.” Reclaiming Class: Women, Poverty, and the Promise of Higher Education in America. Eds. Vivyan Adair and Sandra L. Dahlberg. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2003. 25-52.

- American Princess. NBC and Granada Entertainment. 2005 – present.

- Andrejevic, Mark. Reality TV: The Work of Being Watched. New York: Rowman and Littlefield, 2004.

- Australian Princess. Granada. 2007.

- Balsamo, Anne. “On the Cutting Edge: Cosmetic Surgery and the Technological Production of the Gendered Body.” Camera Obscura 28 (1992): 207-237.

- Banales, Victoria M. “‘The Face Value of Dreams:’ Gender, Race, Class, and the Politics of Cosmetic Surgery.”Beyond the Frame: Women of Color and Visual Representation. Eds. Nerferti X.M. Tadiar and Angela Y. Davis. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. 133-152.

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah. The Most Beautiful Girl in the World: Beauty Pageants and National Identity. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah and Laura Portwood-Stacer. “‘I just want to be me again!'”: Beauty Pageants, Reality Television and Post-feminism.” Feminist Theory 7 (2006): 252-272.

- Barnes, Natasha. “Face of the Nation: Race, Nationalisms and Identities in Jamaican Beauty Pageants.”The Massachusetts Review 35 (1994): 471-92.

- Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. Trans. Annette Lavers. New York: Hill and Wang, 1972.

- Bartky, Sandra Lee. “The Pedagogy of Shame.” Feminisms and Pedagogies of Everyday Life. Ed. Carmen Luke. Albany: University of New York Press, 1996.

- Beckford, James. Social Theory and Religion. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: BBC/Harmondsworth, 1972.

- Bhaskaran, Suparna. Made in India: Decolonizations, Queer Sexualities, Trans/National Projects New York: Routledge, 2004.

- The Biggest Loser. 3 Ball Productions. 25/7 Productions. Reveille LLC. 2004 – present.

- Blum, Virginia. Flesh Wounds: The Culture of Cosmetic Surgery. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

- Bordo, Susan. Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture and the Body. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

- Brand New You. Channel 4, British Broadcasting Company. 2005.

- Brush, Pippa. “Metaphors of Inscription: Discipline, Plasticity and the Rhetoric of Choice.” Feminist Review58 (1998): 22-43.

- Carrison, Dan. “Finding ‘The New You.'” Journal of Longevity 13, 10 (20 Nov. 2007).http://www.journaloflongevity.com/publish/printer v147 p6.asp Accessed 11/27/2007.

- Case, Tony. “Nely Galan, Inc.” Marketing Y Medios (Sept. 2004).http://www.nelygalan.com/press/mym1.htm. Accessed 1/28/2005.

- The Celebrity Apprentice. Trump Productions LLC. 2008.

- Chapkis, Wendy. Beauty Secrets: Women and the Politics of Appearance. London: South End Press, 1986.

- Cohen, Colleen Ballerino, Richard Wilk, and Beverly Stoeltje, eds. Beauty Queens on a Global Stage: Gender, Contests, and Power. New York: Routledge, 1996.

- Covino, Deborah Caslav. Amending the Abject Body: Aesthetic Makeovers in Medicine and Culture. SUNY Press, New York, 2004.

- Craig, Maxine Leeds. Ain’t I a Beauty Queen: Black Women, Beauty, and the Politics of Race. New York, Oxford, 2002.

- —–. “Race, Beauty, and the Tangled Knot of Guilty Pleasure.” Feminist Theory 7 (2006): 159-177.

- The Craze. Keep Clear. 2006.

- Davis, Kathy. Dubious Equalities and Embodied Differences: Cultural Studies on Cosmetic Surgery. Lanham, MD: Roman and Littlefield, Lanham, 2003.

- —– Reshaping the Female Body: The Dilemmas of Cosmetic Surgery. New York: Routledge, 1995.

- Deery, June. “Interior Design: Commodifying Self and Place in Extreme Makeover, Extreme Makeover: Home Edition, and The Swan.” The Great American Makeover: Television, History, Nation. Ed. Dana Heller. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006: 159-174.

- Deserving Design. LMNO Productions. 2007 – present.

- DiPiero, Thomas. White Men Aren’t. Durham: Duke University Press, 2002.

- Dr. 90210. E! Networks Prod. 2004 – present.

- Draper, Electra. “Jesus May Save, but Christians Spend.” Denver Post (24 Dec. 2007)www.denverpost.com/breakingnews/ci_7789121 Accessed 1/10/08.

- Egan, R. Danielle and Stephen D. Papson. “‘You Either Get It or You Don’t:’ Conversion Experiences and the Dr. Phil Show.” Journal of Religion and Popular Culture X (Summer 2005).http://www.usask.ca/relst/jrpc/art10- Accessed 3/10/07.

- Extreme Makeover. Lighthearted Entertainment. 2003 – 2007.

- Extreme Makeover: Home Edition. Endemol USA. 2004 – present.

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books, 1995.

- Fraser, Suzanne. Cosmetic Surgery, Gender, and Culture. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

- Frost, Liz. “Theorizing the Young Woman in the Body.” Body and Society 11.1 (2005): 63-85.

- Galán, Nely. The Swan Curriculum: Create a Spectacular New You with 12 Life-Changing Steps in 12 Amazing Weeks. New York: Regan Books, 2004.

- Gamman, Lorraine, ed. The Female Gaze: Women as Viewers of Popular Culture London: Women’s Press, 1988.

- Gilman, Sander. Making the Body Beautiful: A Cultural History of Aesthetic Surgery. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999.

- Gimlin, Debra. Body Work: Beauty and Self-Image in American Culture.Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

- Gray, Herman. Watching Race: Television and the Struggle for Blackness. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995.

- Green, Michelle and Lipton, Michael. “Sixteen Swan wannabes went under the knife–and TV’s makeover obsession goes under microscope.” People 7 June 2004: 58-63.

- Grosz, Elizabeth. Volatile Bodies: Toward A Corporeal Feminism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

- Haiken, Elizabeth. Venus Envy: A History of Cosmetic Surgery. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1997.

- Halberstam, Judith. Female Masculinity. Durham: Duke University Press, 1998.

- Harney, Alexandra. “The China Doll Revolution.” Financial Times (5 Nov. 2005).

www.howardwfrench.com/archives/2005/11/16/

the_china_doll_revolution_the_beauty_pageant_once_the Accessed 1/28/2007.

_wests_symbol_of_oppression_of_women_has_become_the- _easts_champion_of_opportunity.

- Heller, Dana, ed. The Great American Makeover: Television, History, Nation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

- —–. Makeover Television: Realities Remodeled. London: I.B. Tauris, 2007.

- Holliday, Ruth and Jacqueline Sanchez Taylor. “Aesthetic Surgery as False Beauty,” Feminist Theory 7 (2006): 177-195.

- hooks, bell. Sisters of the Yam: Black Women and Self-Recovery. Boston: South End Press, 1993.

- How Do I Look? Style Network Productions. 2004 – present.

- Instant Beauty Pageant. Earth Angel Productions. 2006 – present.

- I Want a Famous Face. Pink Sneakers Productions. 2004 – present.

- Johnson-Woods, Toni. Big Bother: Why Did That Reality Show Become Such a Phenomenon? St. Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 2002.

- Kaw, Eugenia. “Opening Faces: The Politics of Cosmetic Surgery and Asian American Women.” Many Mirrors: Body Image and Social Relations. Ed. Nicole Sault. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1994. 241-265.

- Kibbey, Ann. Theory of the Image: Capitalism, Contemporary Film, and Women. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2005.

- Ladette to Lady. RDF Television. 2005 – present.

- Lofton, Kathryn. “Practicing Oprah; or, The Prescriptive Compulsion of a Spiritual Capitalism.” The Journal of Popular Culture 30. 4 (2006): 599-621.

- Lowney, Kathleen S. Baring Our Souls: TV Talk Shows and the Religion of Recovery. New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1999.

- Made Over in America. Wegenstein Bernadette and Geoffrey Alan Rhodes, producers and directors. First Run/Icarus Films. 2007.

- Maxed Out. RTR Media. Style. 2007 – present.

- Miami Slice. September Films. 2004.

- Mo’Nique’s F.A.T. Chance. Oxygen Media. 2006 – 2007.

- Mol, Hans.Identity and the Sacred: A Sketch for a New Social Scientific Theory of Religion. New York: Free Press, 1976.

- Morgan, Kathryn Pauly. “Women and the Knife: Cosmetic Surgery and the Colonization of Women’s Bodies.”Hypatia 6.30 (1991): 25-53.

- Moseley, Rachel. “Makeover Takeover on British Television.” Screen 44 (2000): 299-314.

- Motley, Clay. “Making Over Body and Soul: In His Steps and the Roots of Evangelical Popular Culture.” The Great American Makeover: Television,

- History, Nation. Ed. Dana Heller. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

- Mulvey, Laura. “Afterthoughts on ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ inspired by Duel in the Sun.”Framework 15-17 (1981):12-15.

- —–. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen. 16:3 (1975): 6-18.

- National Body Challenge. LMNO Productions. 2006 – 2007.

- Neale, Steve. “Masculinity as Spectacle.” Screen 24.6 (1983): 2-16.

- Negra, Diane, ed. The Irish in Us: Irishness, Performativity, and Popular Culture. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006.

- Oldenberg, Ann. “‘Olympics’ of Makeovers Ready to Take Flight.” USA Today (7 April 2004): 3D.

- Oza, Rupal. “Showcasing India: Gender, Geography, and Globalization.” Signs26.4 (2001): 1067-1095.

- Palmer, Gareth. Discipline and Liberty: Television and Governance. Manchester University Press, 2002.

- —–. “On Our Best Behavior.” Flow 5:5 (Oct. 2006) jot.communication.utexas.edu/ flow/?searchbyline=Gareth%20Palmer Accessed 1/18/2007.

- —–. “Video Vigilantes and the Work of Shame.” Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media 48 (2006): 1-12. www.jumpcut.org Accessed 1/18/2007.

- Parameswaran, Radhika. “Global Queens, National Celebrities: Tales of Feminine Triumph in Post-Liberalization India.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 24.4 (2004): 346-370.

- Peiss, Kathy Lee. Hope in a Jar: The Making of America’s Beauty Culture. New York: Metropolitan, 1998.

- Petre, Jonathan. “Huggable Urns and Coffin Candy for ‘Kitchmas.'” London Daily Telegraph (30 Nov. 2007).www.telegraph.co.uk Accessed 1/10/2008.

- Pitts-Taylor, Victoria. Surgery Junkies: The Cultural Boundaries of Cosmetic Surgery. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2007.

- Pliagas, Linda. “Can Ugly Ducklings Become Beautiful Swans?” Hispanic Magazine September 2004.http://www.hispaniconline.com/magazine/2004/sep /Features/uglyducklings.html Accessed 12/30/2004.

- Poster, Mark. “Swan’s Way: Care of the Self in the Hyperreal.” Configurations15.2, forthcoming 2008.

- Roediger, David. The Wages of Whiteness: Race and The Making of the American Working Class. London: Verso, 1991.

- Roof, Judith. “Working Gender/Fading Taxonomies.” Genders 44 (2006).

- Runkle, Susan. “Making Miss India: Constructing Gender, Power, and the Nation.” South

- Asian Popular Culture 2.2 (2004): 145-59.

- “Sarandon Speaks,” More (Oct. 2004): 126, 200.