Minnesota’s Hot Mamas: An interview with Joanna Inglot

[1] KLEIN: In your book WARM: A Feminist Art Collective in Minnesota you chronicle the history of the Women’s Art Registry of Minnesota, a woman’s art collective and gallery based in Minneapolis. In the introduction, you write that “thirty years after the founding of the WARM collective no studies about it had been written or published, even though the group has been well-known in Minnesota and recognized nationwide as one of the major feminist art cooperatives in the United States (xiv).” I wonder if you could begin by talking about how and why you became interested in WARM and what motivated you to propose an exhibition of 12 members of the WARM collective to the Weisman Art Museum of the University of Minnesota?

[2] INGLOT: I first heard about WARM when I began teaching art history at the College of St. Catherine in St. Paul. One of my colleagues in the Art Department told me that the first registry of slides of a feminist art collective called WARM had been housed in my office. Since that moment I have been haunted by the spirit of WARM and I felt compelled to learn more about the collective. I began to meet artists who once belonged to the group. I got to know their work. Over time I developed a strong sense of professional commitment to document the work of this remarkable group of women who have gone practically unnoticed in the field of feminist art history. I was teaching a course entitled “Women in the Arts” at the same time and came across a photograph of the WARM Collective in Norma Broude and Mary Garrard, ed., The Power of Feminist Art, but that was it. I was surprised to discover that although many feminist circles in the country had heard of WARM and that the collective was well known in the Twin Cities there were no significant art historical analyses or historical studies that examined the nature and the contributions of the collective to feminist art movement and/or cultural life in Minnesota. Moreover, I realized that beyond the importance of this group for feminist art history that the members of WARM had produced some very good work. After seeing the work of many of the artists associated with WARM I was struck with the quality. I remember thinking that their art was as good as anything I was teaching about in my Women in the Arts class. I think it was that recognition that motivated me to propose an exhibit to the Weisman Art Museum. Since the museum does not have a large exhibition space, I had to limit the exhibit to 12 members. I selected long-standing members whose work gave a good cross-section of work produced by the collective.

[3] KLEIN: How did working on the exhibition “WARM: 12 Artists of the Women’s Art Registry of Minnesota” and book/catalogue differ from writing your first book: The Figurative Sculpture of Magdalena Abakanowicz: Bodies, Environments, Myths? Did you encounter any challenges by shifting your emphasis from a well-known artist to a group of feminist artists that had almost disappeared from art history/history?

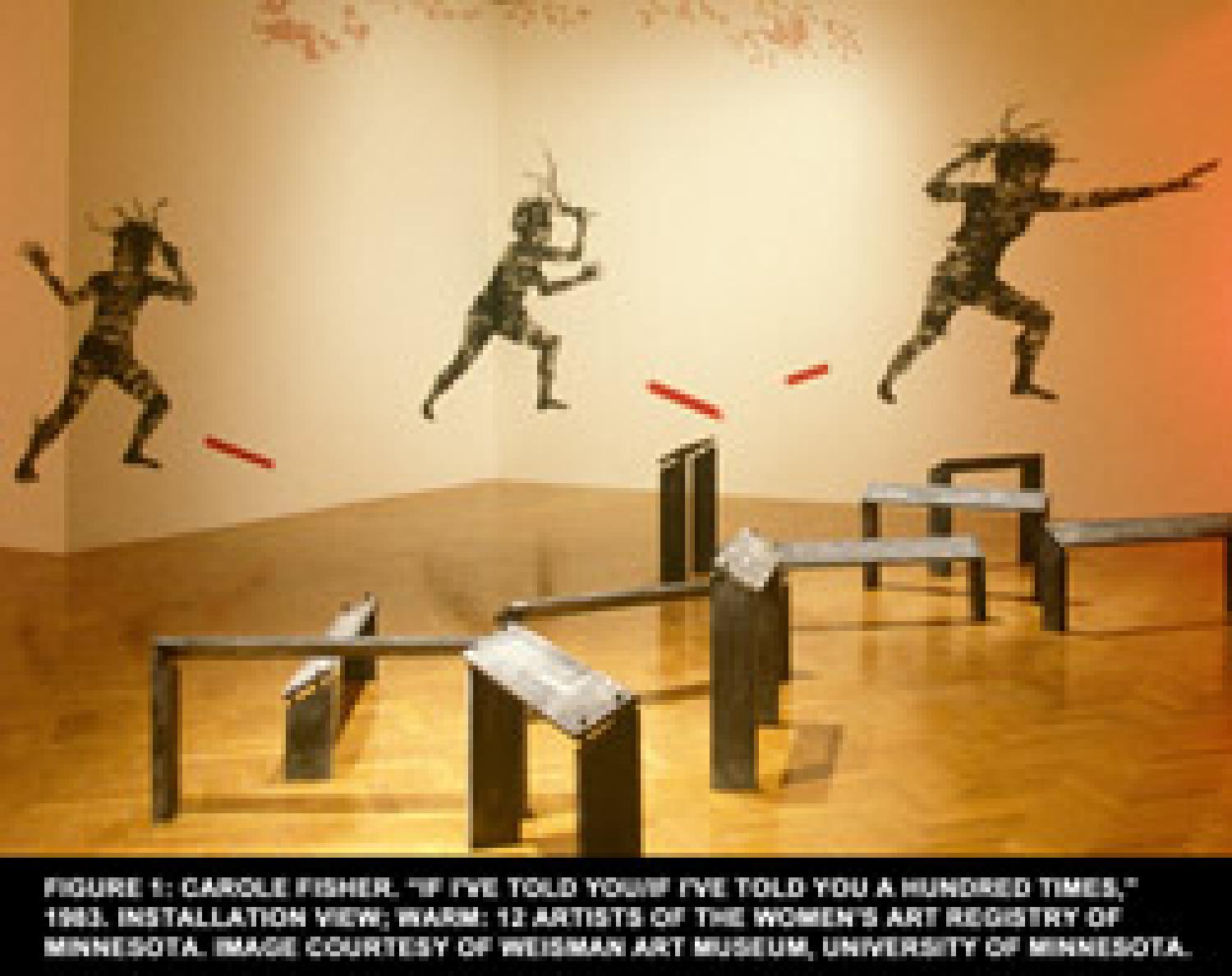

Figure 1: Carole Fisher. If I’ve Told You/If I’ve Told You a Hundred Times, 1983. Installation View: “WARM: 12 Artists of the Women’s Art Registry of Minnesota.” Image courtesy of Weisman Art Museum, University of Minnesota.

[4] INGLOT: My experience of working on these two books was quite different although surprisingly there were still many similarities. Abakanowicz was well-known but scholarship on her work was rather skimpy. Abaknowicz’s work and her persona were veiled by the myth of the outsider loner artist who worked in the deep isolation of Communist Eastern Europe. Yet she is someone who has become a leading voice for artists behind the Iron Curtain. One of my major goals was to de-mythologize the artist and to present her work in the context of Polish sculpture and in dialogue with the international art scene. I also addressed the complexity of the artist’s attitudes toward contemporary politics and the troubled history of her native country. In that book I wanted to draw attention to the lack of scholarship on the art of Poland and the marginalization of the entire region of post-World War II East-Central Europe caused by Cold War biases that impelled critics and art historians to see Eastern Europe as a uniformly backward and culturally isolated region, mimicking the developments of the Soviet Union. The political climate in which WARM developed was obviously quite different. I noticed, however, that the history of WARM also suffered from similar cultural and regional marginalization. The contemporary art produced in the Midwest, including Minnesota, was and still is often seen by critics and art historians as parochial, derivative, and unworthy of close scrutiny. Therefore, in this project I felt it was important to challenge this general outlook in order to present this group in a larger national context. I wanted to demonstrate the lively artistic and feminist environment that developed in the Twin Cities during the 1970s-1990s. In both cases, I had to create a context for an artist/group of artists and recreate the cultural climate in which they worked. But, of course, working with one artist versus a collective is quite different. The WARM project required many more negotiations, which sometimes were difficult or even impossible to achieve.

[5] KLEIN: You interviewed many artists involved with WARM for this book, including a number of women who didn’t end up in the exhibition, such as Catherine Jordan, who worked as an administrator at WARM, Judy Stone Nunneley, a printmaker, and Terry Schupbach-Gordon, an artist and disability activist. How did you decide whom to interview? Did you seek out certain women in order to get a more balanced account of the WARM gallery?

[6] INGLOT: There were one hundred members of WARM and I knew from the beginning that I would not be able to interview all of them in the time frame I had for this project. While doing research in the archives I created a list of those I felt I needed to interview. The actual interviews led me to other people because of specific issues I wanted to address in my book. I definitely did my best to get the most balanced perspective I possibly could, and interviewed many women who did not end up in the book or in the exhibition.

[7] KLEIN: The task of organizing and curating the exhibition must have been daunting. As you pointed out, the roster of members that belonged to WARM from 1976-1991 has 100 names on it. You made the decision to include 12 artists: Harriet Bart, Hazel Belvo, Sally Brown, Elizabeth Erikson, Carole Fisher, Linda Gammell, Vesna Krezich Kittelson, Joyce Lyon, Susan McDonald, Patricia Olson, Sandra Menefee Taylor, and Jantje Visscher. Most of these artists were involved with WARM for an extended period of time. Carole Fisher, for example, whose installation on the topic of rape is reproduced above (figure 1), was responsible for starting the innovative Arts Core Program dedicated to feminist education at the College of St. Catherine. After that program folded, she was instrumental in helping to found WARM. The one exception is Linda Gammell who although a founding member was only involved for 3 years. Why was she included along with the other, longer term members?

[8] INGLOT: One of the greatest difficulties of curating the WARM exhibition, as it always is with any substantial collective, was the selection of artists. Because of limited space at the Weisman Art Museum, I had to limit the numbers of featured artists significantly. Out of 100 artists who belong to WARM, I selected twelve, which I believed represented the diversity of the group in style, subject matter, mediums and engagement with feminist issues. I focused on long-term members. Almost all of them were in WARM from the beginning to the [fiscal] crisis in 1986. I added Linda Gammell (who was one of the founders of WARM) mainly because she was a photographer, and I wanted to feature some photography. I was also interested in Gammell because she continued to work in collaboration with Sandra Menefee Taylor. This was a feminist collaboration that developed from WARM and I wanted to highlight the notion of collaboration as feminist practice in the show.

[9] KLEIN: What sort of careers have the artists included in the WARM exhibition at the Weisman Art Museum had since WARM closed?

[10] INGLOT: Most of them have worked as professors of art, teaching in local colleges and universities, Minneapolis College of Art and Design, and the University of Minnesota. Some developed independent careers or run art studio programs. The majority, however, have been working as art educators since their involvement with WARM.

[11] KLEIN: You credit the pivotal stimulus for the formation of WARM’s feminist identity with art education, specifically the curriculum and events taking place at the College of St. Catherine in St. Paul. A 1973 lecture by Judy Chicago inspired Carole Fisher, Sr. Judith Stoughton, and Sr. Ann Jennings to found the Arts Core Program as part of the Visual Arts Department. Modeled on the FSW (Feminist Studio Workshop) founded by Chicago, Arlene Raven, and Sheila de Bretteville for the Los Angeles Woman’s Building, the Arts Core Program encouraged students to make work out of personal experience, consciousness raising sessions, and feminist concerns. It also sponsored workshops and lectures by feminist artists and scholars including Raven, de Bretteville, Miriam Schapiro, Ruth Iskin, Betsy Damon, Elaine de Kooning, Marisol Escobar, and Lucy Lippard. The Arts Core Program only lasted for one year. Could you discuss how the radical pedagogical approach of the Arts Core Program influenced WARM’s program of exhibitions, lectures, conferences, and pedagogy?

[12] INGLOT: I would like to clarify that my assertion regarding the impact of the Arts Core Program at St. Catherine referred only to the early stages in the formation of the collective. The Arts Core Program lasted one year, but it brought many important feminist artists and speakers to the College of St. Catherine that women artists from the Twin Cities flocked to see and hear. Practically everybody who was involved in organizing WARM credits these events at St. Kate’s as path-breaking. Lectures by feminist artists and critics and exhibitions of feminist art on view in the college art gallery galvanized the emerging feminist community there and inspired artists such as Fischer, Hazel Belvo, Sally Brown, Elizabeth Erickson, Linda Gammell, Joyce Lyon, and many others to create a collective. The discussions, debates, and information about feminism in the US that the Arts Core Program provided were crucial in the consolidation of the WARM collective in the mid-1970s. I don’t believe that the Arts Core Program’s radical pedagogical approach had as much influence on the program of exhibitions, lectures, conferences, and pedagogy that later took place at WARM Gallery by itself. It was the climate that it created in the early 1970s in the Twin Cities and the connections established with other feminist artists in the country during this amazing time at St. Kate’s that were crucial for the emergence of WARM. I think WARM modeled itself more on the feminist collectives that were established on the east and west coasts, particularly the west coast and the Los Angeles Woman’s Building rather than on the pedagogy of the Arts Core Program. For instance, WARM appropriated many organizational features of the New York’s A.I.R Gallery and their educational philosophy was inspired by the FSW and the Los Angeles Woman’s Building.

[13] KLEIN: During its 15 year run, WARM mounted a number of exhibitions and sponsored a major conference in honor of its 10th year anniversary. Could you discuss several of the most significant exhibitions and events that took place under its auspices?

[14] INGLOT: From the onset, the exhibitions and events produced by WARM were characterized by innovative programming. The Visiting Artist Program brought many well recognized women artists from all over the country to the Twin Cities. WARM’s programming culminated with the national conference “Contemporary Women Artists in the Visual Arts” that took place in 1986. From 1980 to 1986 WARM became a hub of feminist cultural life in the Twin Cities. As their visibility increased, WARM members took the opportunity to stage large-scale exhibitions, which ranged from exhibitions of historical feminist art to the work of artists who were members of WARM. “Private Collectors and Art by Women” (1984), for instance, featured art by prominent 19th and 20th century women artists such as Mary Cassatt, Rosa Bonheur, Käthe Kollwitz, Sonia Delaunay, Helen Frankenthaler, Grace Hartigan, and Louise Nevelson. “WARM: A Landmark Exhibition” (1984) at the Minnesota Museum of Art at the Landmark Center in St. Paul—the largest and the most comprehensive show of WARM—showed the work of 37 WARM members and drew hundreds of visitors to the show. One of the greatest accomplishments of WARM (and the event of which they were most proud) was the national multidisciplinary conference that they organized in the fall of 1986 to mark the 10th year anniversary of the Gallery. This conference brought together more than 400 women artists, art historians, and critics from across the country. It was literally an extravaganza of panels, lectures, film projections, discussions, and exhibition tours, combined with music, parties, and other kind of entertainment. Well-renowned speakers such as Sandra Langer, Eleanor Heartney, Elsa Honing Fine, Joanna Freuh, Judith Wilson, and Patricia Mainardi presented at the conference. Performance artists Besty Damon, Suzanne Lacy, and Laurie Beth Clark, along with painters May Stevens and Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith came to the Twin Cities to take part in the conference. Along with the conference, WARM sponsored exhibits in the Twin Cities’ museums and galleries, and arranged bus tours for people so they could move easily from one place to another. It was a major celebration—and WARM, indeed, had much to celebrate as it established itself not only as a prominent local gallery but as a nationally recognized participant in feminist culture.

[15] KLEIN: The sheer diversity of programs, conferences, visiting artists and exhibitions that WARM produced, in spite of its dependence on public funding, membership dues, and the sweat equity of its members is really quite astonishing, particularly in comparison with the Woman’s Building, which began to lose steam by the mid-80s. I can’t help but wonder if this had something to do with the type of art exhibited at WARM, which was object-based. Unlike the A.I.R. Gallery, the FSW, and the Woman’s Building, where alternative art forms such as performance, video, and installation were embraced, WARM’s gallery showed mostly painting, which is more marketable. Were there any spaces in Minnesota that did show more experimental feminist art? Why were the members of WARM less inclined to embrace more experimental media?

[16] INGLOT: Indeed, WARM was dominated by painters, but there were also artists working with performance, installation, video, photography, and/or graphic design. I think that the predominance of painters in the group can be explained by the rather traditional training that many of these artists received in the Midwestern colleges and universities that they attended. In addition, the selection process for new members set in place at WARM was probably more rigorous and controlled than in other places. The initial group of governing members who were responsible for establishing the gallery was comprised primarily of painters who adopted a highly selective screening procedure for admittance to the gallery. I think they were probably more sympathetic to artists who showed similar directions to them in their work. Linda Gammell and Bonita Wall were exceptions, especially in the beginning, and they aligned themselves with a film collective and other smaller collectives active in St. Paul, where they could show more experimental work. But there was not another place besides WARM for young women artists to show experimental feminist work in Minneapolis on a consistent basis. WARM exhibited some experimental work but perhaps not as much as one could see in New York City or Los Angeles.

[17] KLEIN: Janice Helleloid, who was a member of WARM from 1976-1977, complained in the Lesbian issue of Heresies that there had been “two specific instances of the art world in the Twin Cities politically using the label ‘lesbian’ to exert community control over women’s groups (44).” The first time happened when the Women’s Arts Core Program was terminated after one year amidst charges of being a lesbian program. Subsequently, WARM was also labeled a lesbian organization, causing many of its members to become concerned about the gallery’s public image. Could you address the issue of lesbianism in relationship to the Women’s Arts Core Program and WARM? Why do you think that lesbianism was of much more concern to the feminist art community in Minnesota than it was in either Los Angeles or New York?

[18] INGLOT: The Arts Core Program was terminated mainly because of disagreements, rumors, and accusations that were spread by some faculty members of the Art Department, who objected to the general conceptual basis of the program, the presumed financial burden for the department, and inappropriate pedagogical methods (or what they called “psychological manipulation” of young women) along with the alleged propagation of lesbianism. In fact, most of these were discussed openly at the faculty meetings during the review of the program at St. Kate’s. The issue of lesbianism, however, was never addressed outwardly. It circulated as a rumor, spread by faculty who were nervous about the fact that the instruction was carried out “behind the closed doors” (intended in actuality to reflect the “room of one’s own” idea). I believe that some faculty who taught in the program were seen as lesbians, which also contributed to all the hype around lesbianism in the program. The official documents deposited in the archives, however, do not show that this was an important issue in the formal evaluation of the program by the Educational Policies Committee at St. Catherine. Janice Helleloid, just like many other students in the program, must have felt that these rumors contributed to the termination of a valuable and successful program. All of the students were hurt and disappointed because of that unstated charge.

[19] INGLOT: The same problem showed up at WARM. Helleloid was right– the WARM gallery was seen by many in the art world and the community as a “dyke gallery.” The truth was that many of the members of WARM were lesbians, quite a few of whom were out. Most of them were uncomfortable with discussing their sexuality publicly. Being aware that they lived in a homophobic society (be it Minnesota or other parts of the country), many were wary of becoming marginalized as a politicized lesbian community. Again, there was nothing official coming from the art world that labeled WARM as a lesbian gallery. There were only rumors and perceptions that it was a lesbian gallery floating around. Therefore many WARM members wanted to distance themselves from that idea in fear that it would negatively impact the reception of their work and their gallery.

[20] INGLOT: I would like to point out that in the Twin Cities lesbian activism and culture was strong–just not at WARM. It flourished primarily in the Coffee House Collective and other women’s spaces such as Amazon Bookstore, the Lesbian Resource Center, Chrysalis, Art at the Foot of the Mountain Theater, and Twin Cities Female Liberation Group. WARM hosted events with lesbian poets and writers, including those associated with literary groups such as the Loft, Women Poets of the Twin Cities, and other collectives, but the gallery never organized their own exhibitions or symposia on lesbian issues, and rarely showed works with specifically lesbian content. I think that WARM was not as radical and politicized as A.I.R, SoHO 20 in New York or the feminist art collectives in California. The Midwest, in general, and Minnesota with its Lutheran cultural tradition in particular, was much more conservative in regards to tackling issues of sexuality–particularly lesbian sexuality. These debates did not spread much beyond the places that I mentioned above during this period.

[21] KLEIN: Do you think that the members of WARM were better able to deal with issues regarding race and disability?

[22] INGLOT: Oh, no, not at all. In fact this can be seen as one of the major criticisms of WARM. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, WARM rarely tackled issues of difference and diversity. There were members in the group, such as Terry Schupbach, who called for a more radical feminist agenda within the collective and who actively championed the interests of disadvantaged groups. She argued that WARM should welcome black women artists, ethnic minorities, and artists with disabilities. The majority of WARM was not interested in moving in this direction. Like other second-wave feminist groups, WARM was dominated by white, middle-class, well educated women who were focused on their own interests. By and large, they treated the issues of race, ethnicity, and disability as secondary concerns. Artists of color were not well integrated into the women’s art movement and exhibition planning across the country. In Minnesota, which was and still is predominantly white and Northern European in heritage, this rift was even larger. In a region with small minority communities, especially in comparison with New York and Southern California, there seemed less urgency to debate many of the racial issues that strongly resonated elsewhere. Frankly, there was not much consciousness about this issue at that time among the members of the collective. WARM responded to the issue of multiculturalism and disability gradually over the 1980s and early 1990s. The most systematic attempt to reach minority women artists in Minnesota appeared after 1986, when WARM officially amended its mission statement to promote the work of women artists of all races and ethnic backgrounds. These efforts became most visible in their Mentor Program after 1987, when the organization actively sought women of color in the Twin Cities to join the ranks of its mentors and protŽgŽes.

[23] KLEIN: After 1986, several members of WARM, including Sandra Menefee Taylor, Jantje Visscher, and Susan McDonald, were involved in community outreach to impoverished rural communities through the MAX (Minnesota Arts Experience) Program. Do you think that the impetus to do that sort of community outreach came from the history of grassroots activism in Minnesota, which you describe in so much detail? How did this outreach compare with the kinds of programs generated on the east and west coasts?

[24] INGLOT: I think that the community outreach by members of WARM was unique in the history of feminist collectives. I really don’t know of efforts by other collectives to support new generations of artists like WARM did through their Mentor Program, or to reach out to culturally disadvantage communities in rural areas of the state by organizing workshops, lectures, and exhibitions in these areas. I believe that this commitment to community was deeply rooted in the Minnesota history of grassroots activism, which goes back to the 19thcentury. Scandinavian and Lutheran traits of social activity and community solidarity was ingrained in Minnesota culture and they resurfaced strongly in the socio-political ferment of the late 1960s and early 1970s, shaping much of the thinking of WARM and other collectives. By and large, all of these collectives were influenced by this heritage, which I discuss in much more detail in my book. WARM really took an extra step by running programs in small towns and rural regions. Some of the members of WARM were born in rural Minnesota, others were only a generation removed from it, and they were interested in giving back to their community and reaching out to rural populations. No other women’s art collective in the country developed such generous outreach programming.

[25] KLEIN: Even as the members of WARM were expanding their definition of what it meant to be a practicing artist by developing this unique community outreach program, the gallery and collective were falling on hard times. Eventually the gallery closed in 1991. The multidisciplinary conference that WARM sponsored in 1986 was tremendously successful. At the same time, it precipitated a fiscal crisis from which it was difficult to recover. Many long term members, disillusioned with the prospects of the collective and burnt out on volunteer work, withdrew around that time. What were some of the other factors that contributed to the demise of WARM?

[26] INGLOT: The national conference ended up with a tremendous budget deficit; however WARM managed to pay off the debt within the next two years or so. The gallery could have survived this crisis if the problems had been confined to a budget deficit. There were many artists who were committed to keeping the gallery open and WARM was still attracting the interest of younger women artists. But after the departure of many experienced key members in 1986, WARM could never attain the same cohesiveness and commitment. Many members believed that working together to build the gallery and organize the entire program was the glue that held the collective together. The new generation of artists who joined WARM later on did not have the same attachment to the place. Another important factor in the demise of WARM was that times had changed. There was a general backlash against feminism during the 1980s brought about by the rise of conservative ideology waged by right-wing politicians in the US. This resulted in limited funding, which significantly restricted the various activities of the gallery. Another factor was the rise of academic feminist theory and criticism indebted to postmodern and poststructuralist theories. The definition of feminist art changed dramatically from the early 70s to the early 90s. WARM, which arose from the cultural feminism of the 70s could not find the same unified sense of purpose amid new debates within feminism, and would have needed to radically redefine itself as a feminist organization to survive this crisis.

[27] KLEIN: You have pointed out that in spite of the renewed interest in 70s feminist art in recent years there has been a disregard for the developments and accomplishments of feminist art collectives working outside of the cultural hubs of New York and Southern California. 2007 saw a renewed interest in feminist art, particularly historical feminist art. Two major feminist exhibitions with an international focus—”Wack! The Art of the Feminist Revolution” and “Global Feminisms”—opened almost simultaneously in Los Angeles and New York. ARTnews, which first published Linda Nochlin’s “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists,” in 1971, devoted the February 2007 issue to Feminist Art. The Feminist Art Project (http://feministartproject.rutgers.edu/), based at Rutgers University in New Jersey organized a symposium in conjunction with the College Art Association Meeting in New York City devoted to feminist art and art history. Given the events of the past year, do you still feel that the feminist art organizations in the Midwest have been left out of this history, and if so, why?

[28] INGLOT: I really appreciate the recent efforts by feminist art historians and critics, museum professionals, and other committed activists to revive interest in feminist art in the United States, including the feminist art made in the 70s. The year 2007 was indeed remarkable because two major feminist exhibitions opened, both of which were excellent. These exhibitions were both historic and international in scale, highlighting contemporary developments in feminist art around the world. Maura Reilly, the curator of “Global Feminisms,” came to see the WARM exhibition. We did a co-presentation on feminism in the US and around the globe. It felt wonderful to stage the exhibition at the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis at the same time as “Wack!” and “Global Feminisms” and experience the renewed power of feminist art in the art world. We had to wait for this a long time. The Feminist Art Project, too, is another important initiative that promises to ensure that feminist art stays at the center of attention and will be well documented in the future. I am particularly grateful that the Feminist Art Project tries to facilitate a network with regional centers throughout the US because as I have shown in my book feminist art and debates are happening outside of New York and California. In spite of all this attention, we still don’t know much about feminist art and feminist art organizations in the Midwest. When I looked for organizations with which to compare WARM, for example, I had no information on comparable organizations in other parts of the Midwest. I would like to know something more about the feminist collectives and the feminist art scene in Chicago, Detroit, or Cleveland, for instance. It is not just that Midwest is languishing; other parts of the country are as well. I think that the preference for art made in New York and California has been so deeply engrained in our cultural consciousness that it will take sustained scholarly and critical interest in feminist art made outside of those areas to change the landscape of feminist art history.

Works Cited

- Broude, Norma and Mary Garrard, ed. The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact. New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc., Publishers, 1994.

- Butler, Cornelia H. and Lisa Gabrielle Mark, ed. Wack! Art and the Feminist Revolution. Los Angeles: The Museum of Contemporary Art and Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007.

- “Feminist Art: The Next Wave” ARTnews 106.2 (February 2007).

- Helleloid, Janice. “What Does Being a Lesbian Artist Mean to You?”Heresies 3 “Lesbian Art and Artists” (Fall 1977): 44-45.

- Inglot, Joanna. The Figurative Sculpture of Magdalena Abakanowicz: Bodies, Environments, Myths.Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

- Inglot, Joanna. WARM: A Feminist Art Collective in Minnesota.Minneapolis, MN: Weisman Art Museum and University of Minnesota Press 2007.

- Nochlin, Linda. “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”ARTnews 69.1 (January 1971): 22-39; 67-71.

- Reilly, Maura and Linda Nochlin, ed. Global Feminisms: New Directions in Contemporary Art. New York: Brooklyn Museum of Art and London: Merrell, 2007.