Jet-Man Meets Cover Girl at the F-111: Gender and Technology in James Rosenquist’s F-111

In my hungry fatigue, and shopping for images, I went to the neon fruit supermarket, dreaming of your enumerations!

—Allen Ginsberg, “A Supermarket in California” (1955)

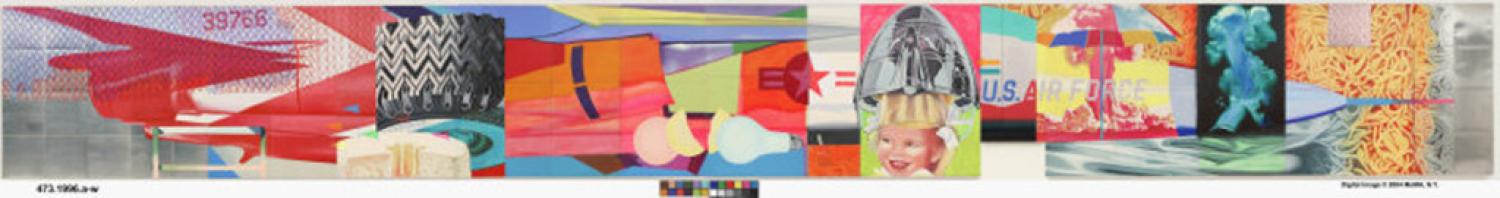

Figure 1

James Rosenquist (b. 1933). _F-111_. 1964-65. Oil on canvas with aluminum. 10′ x 86′ overall. Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hilman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). (00473.96a-w). Art (c) James Rosenquist/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Reproduction of this image, including downloading, is prohibited without written authorizeation from VAGA, 350 Fifth Avenue, Suite 2820, New York, NY 10118. Tel: 212-736-6666; Fax: 212-736-6767; email: info@vagarights.com

[1] James Rosenquist’s F-111 (1964-5, fig 1) manipulates the visual codes of American Cold War culture to prophesy a future when cyborgs will plunder the neon fruit supermarket for their post-nuclear families. Rosenquist populates F-111 with two cyborgs, two bionic humans enmeshed in the machinery of Cold War consumerism: a grinning girl under a hairdryer peers at a Day-Glo landscape, while a deep-sea diver exhales a mushroom cloud. Like the fragmented, manipulated consumer objects crowding the image, these figures dissolve and reform, providing husks to be inhabited by a cast of gendered characters from modern life: daughter, suburban housewife, Cover Girl, breadwinner, Jet-Man, and Organization Man.

[2] In 1985, Donna Haraway posted a “Manifesto for Cyborgs” in an attempt to formulate a feminist theory free from the dualisms that retrench gendered hierarchies such as patriarchy and colonialism. Haraway visualized “an ironic, political myth” centered on cyborgs, “creatures of a post-gender world” that live in an “integrated circuit,” a network simultaneously public and private, industrial and domestic (173, 175, 193). In “Homes for Cyborgs,” architectural historian Anthony Vidler characterized Haraway’s work as a political maneuver intended to create awareness of both the extent to which these dualisms shape the theory and practices of modern life and the possible coexistence of “incompatible things” in a new order (Haraway 173). Jen Fleissner noted that “one of [Haraway’s] trickier but most crucial moves was to invoke the cyborg simultaneously as a sign of our present postmodern condition (and hence of late capitalism, the military-industrial complex and all those other bad things) and as a utopian figure, a resource for feminist resistance” (20).

[3] Haraway’s brave new world populated by genderless technobodies dissolves boundaries drawn by the modernist systems of the object, the body, the optical, and the home (Vidler 149). Similarly, Rosenquist fashions a new order by using fragmentation, enlargement, repetition, and juxtaposition to fuse organic and inorganic, male and female. Gender determines Rosenquist’s conception of cybernetic culture, as it did Haraway’s myth. The vaginal cake and the phallic jet, the grinning girl and the deep-sea diver personify gender roles established by the American, postwar, consumer economy. Through fragmentation and juxtaposition, Rosenquist explores the relationship between the masculine body and military technology (Jet-Man) and between the feminine body and domestic technology (Cover Girl). Yet like Frankenstein, a creature born of the scientific machinations of the Age of Reason, Jet-Man and Cover Girl, as technobodies of the Atomic Age, marshal resources independent of their creator. F-111 both enacts and subverts Rosenquist’s ironic vision of the cybernetic sublime.

Cover Girl

[4] In June 1972, Rosenquist’s grinning girl appeared on the cover ofArtforum, inaugurating her career as Cover Girl. Here, mechanically reproduced on slick and glossy paper, she serves as a synecdoche for F-111, for Rosenquist’s oeuvre, and for the ideological dualisms of American Cold War culture. For example, scientific progress yielded both technological innovation and the potential for nuclear annihilation, the nuclear family coalesced at the expense of kin networks and multigenerational families, and the revival of domesticity and traditional gender roles assuaged fears concerning national identity (May). Rosenquist endorsed her centrality, emphasizing that “the little girl is the female form in the picture,” and affirmed her presence as an antidote to abstraction: “I thought of taking the face out many times, but then the whole painting would be closer to what is historically the look of abstract painting” (qtd. in Swenson “F-111” 598). Despite Rosenquist’s insistence upon the formal role of his singular muse, “the face,” “the female form” harbors a host of women—daughter, housewife, sex symbol, consumer, and consumed. Cover Girl, her head helmeted by the hairdryer, articulates the relationship between the female body and technology in the American economy of domesticity.

[5] Cover Girl, as daughter, signifies the postwar nuclear family. White, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant, middle class, and suburban; this group established and maintained a cultural norm predicated upon a reaffirmation of domesticity and traditional gender roles. American men and women married earlier and produced more children, thereby making a fervent commitment to family life. The suburban home sheltered the postwar population explosion. Children provided a comforting sense of continuity with a future rendered uncertain by the threat of nuclear annihilation (May 3-5, 12-3, 23), a connection articulated by the mushroom cloud that replicates the shape of the bulbous hairdryer safeguarding the girl. But the same juxtaposition also emphasizes the generational difference of opinion about the inevitability of nuclear destruction: Rosenquist explained, “To me it’s now a generation removed, the post-Beat young people. They’re not afraid of atomic war and think that sort of attitude is passé, that it won’t occur” (qtd. in Swenson “F-111” 599). Accordingly, the grinning girl, the stereotypical daughter of the nuclear family, looks away from the mushroom cloud, oblivious to its presence, and sheltered from reality by the helmet that evokes the U.S. government’s “duck and cover” campaign of the 1950s that would supposedly protect American schoolchildren from a nuclear blast.

[6] Cover Girl, as daughter, also prefigures her future as homemaker, a professional woman at home in a cybernetic environment comprising home appliances, the regimented flora of the suburban landscape, and the female body. In the decades following the end of World War II, technology professionalized homemaking. The woman became a “home economist” by assuming her role as an informed consumer of technologically advanced products intended to increase comfort. Historian Elaine Tyler May notes, “Appliances were not intended to enable housewives to have more free time to pursue their own interests, but rather to achieve higher standards of cleanliness and efficiency, while allowing more time for child care” (171). Technology had mechanized the suburban home, a site ideologically associated with the female body, forging a cyborgian identity for the home economist who accomplished her tasks with the aid of home appliances. Physically liberated from drudgery by the appliance encasing her head, Cover Girl, as home economist, personifies the simultaneously held dualisms of the integrated circuit of the household economy.

[7] The mechanical accoutrements of the modern suburban home also served to armor the female cold warrior in the struggle to assert the superiority of the American domestic economy over the Soviet command economy. In the notorious “Kitchen Debate” between Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and Vice President Richard Nixon at the American Exhibition in Moscow in 1959, Nixon maintained the superiority of both the American model home, replete with commodities, and the American homemaker. For Nixon, the model suburban home served both to diffuse the social unrest that invited communism and to ensconce women firmly in the domestic sphere. The model home, in short, “represented the essence of American freedom,” a freedom predicated upon consumerism (May 16). More, then, was at stake in the purchase of commodities than comfort and convenience. Women, as consumers, “kept American industry rolling and sustained jobs for the nation’s male providers” (May 167). America, although lagging behind in the space race and reaching to close the missile gap, claimed victory in the consumer race by deploying the female cold warrior on the home front. The girl’s hairdryer becomes the aviation helmet of the jet pilot, an association made by the artist. A collage for F-111 modified a magazine advertisement featuring two women under hairdryers sipping Coca-Cola through straws and above them Rosenquist scribbled “pilot – co pilot” (Hopps and Bancroft 292). In a second collage, the artist pasted the same hairdryer over the girl’s head, transforming her into the pilot (Hopps and Bancroft 292). A runner’s hurdle appears at the far left of the composition, under the engines of the jet, evoking the races enacted in the politico-economic sphere.

[8] The Kitchen Debate fundamentally concerned commodities and their relationship to the female body. The technology of the home front enmeshed the female body in the suburban house. Appliances served as extensions of the female body, enabling the homemaker to meet rising standards of domestic hygiene by performing more work in less time (Lupton 15). Nixon asserted that the American homemaker, unlike her Soviet counterpart, need not leave the home to pursue the industrial drudgery of factory work, thereby bolstering the fallacy of the labor-saving domestic device. Freedom from physical labor allowed the American housewife the time to cultivate her physical charms and the energy to proffer them to her provider (May 18-9). Thus, the household appliances that offered autonomy within the domestic sphere also objectified the female body. She became another household appliance designed to increase the comfort of her family. In this vision of Cold War domesticity, the cybernetic homemaker’s uterine hairdryer obediently bears her bionic young.

Figure 2

[9] Rosenquist’s constellation of commodities—the vaginal cake, the uterine light bulbs, and the womb-like hairdryer—underscore the feminization of the home front and the embroilment of the home economist in the Cold War. Food, specifically American mainstream foods such as cake mixes, canned spaghetti, hot dogs, and hamburgers, was deployed in the construction of the U.S. image (Stich 77-109). During the postwar period, manufacturers developed processed foods with reduced preparation times, a development fostered by home appliances such as the refrigerator and the deep-freeze (Stich 83). But processed foods, unlike organic food, require chemical additives to improve color, flavor, and preservation, resulting in cybernetic foodstuff. In F-111, six flags stud the top of the angelfood cake like burning birthday candles. Five flags bear the name of an additive, such as riboflavin or vitamin-D, while the sixth proclaims “food energy.” Many experts bemoaned chemical food additives, even in 1964, as a series of advertisements sponsored by Sugar Information, Inc. demonstrates (fig. 2). These ads, such as the one from July 17, 1964 asking, “Until 1950, who ever heard of sodium n-cyclohexyl-sulfamate?” arose from the feud between the sugar and cola industries, prompted by the advent of diet drinks containing artificial sweeteners. These advertisements spoke directly to the home economist by juxtaposing threateningly scientific words with the photograph of an all-American, active child who requires the food energy provided by sugar, rather than the empty calories of the synthetically sweetened diet drink that, she is told, he needs “like a moose needs a hatrack.” Rosenquist’s flags use the same industrial typeface as the advertisement decrying the synthetic sweetener, and juxtapose the names of these chemicals with the image of Cover Girl, as daughter, threatened by chemical additives, and presumably protected by the expertise of her mother, the home economist. The scale of the cake, the gigantism of the little girl, and the heightened, unnatural colors “celebrat[e] American ingenuity but also giv[e] pause, provoking an awareness of how American’s economic, technological, scientific, and corporate prowess continually threatens to transgress the rational and the natural” (Stich 84). Rosenquist noted the parallel between the angel food cake and the jet when he stated that “the F-111, the plane itself, could be a giant birthday cake lying on a truck for a parade or something—it has even been used like that—but it was developed as a horrible killer” (qtd. in Swenson “F-111” 598). In short, the same technology that facilitates domestic comfort and convenience also produces nuclear weapons and toxic foodstuffs.

[10] The mechanical womb sheltering Cover Girl, as daughter, not only protects her from nuclear radiation and the excesses of science, but also suggests the brainwashing capacity attributed to advertising in the 1960s (Varnedoe and Gopnik). In the wake of the McCarthy Era, the Korean War, and the industrialization of advertising, contemporary critics underscored the ways in which phenomena such as mass media, consumerism, brand-name identification, and suburban living fostered regimentation, conformity, and uniformity (Packard; Whyte). Advertisers promoted consumer loyalty to brand-name goods with identifiable logos and packaging that alleviated the decision-making process prompted by the abundance of the self-serve supermarket (Stich 103). The Firestone tire, like the U.S. Air Force jet, promises to ease the consumer’s mind by ensuring quality, dependability, and trouble-free choices.

[11] Tire advertisements pepper issues of Time magazine from 1963 and 1964, associating the product with masculine triumph at the Indianapolis 500 and with the helplessness of the female, stranded on the roadside where “there’s no man around” (fig. 3).

The advertising copy continues: “She’s stranded. Helpless. A flat tire and no one in sight to change it.” Thankfully, this woman’s husband had purchased the Goodyear Double Eagle with LifeGuard Safety Spare. This advertisement equates the brand-name tire with the male provider and his sexual prowess and reliability, resulting in a corporately-engineered cyborg capable of rescuing damsels in distress. In F-111, the tire looms oppressively over the angel food cake, replicating its annular shape, yet changing the gendered associations from the soft, vaginal funnel of the cake to the hard, treaded rubber tire associated with the automobile, the quintessential expression of American manhood.

[12] Rosenquist may have drawn upon both advertisements and contemporary art when he included the tire in F-111. In the 1962 Happening “The Courtyard,” Allan Kaprow also invested a tire with masculine qualities. He directed his goddess/Cover Girl to climb a mountain and pose on an “altar-bed” for cheesecake photographs. Then a tire swung over her as she reclined on the mattress, missing her body by inches and eliciting gasps from the audience. She drew the tire to herself, which brought down an inverted mountain that swallowed her (Kaprow 114-6). In “The Courtyard,” the tire threatens the girl and then triggers her disappearance, removing her from the public sphere of the performance. Kaprow had also used tires in a 1961 Happening in New York, which he recreated in 1984 at the Whitney Museum of American Art, where he arranged 1,300 tires to resemble a Zen garden. Of the original installation, Kaprow said, “Twenty-three years ago, people were hostile to this sort of thing—they were afraid to move out intoart. People were not used to seeing things outside their normal context” (qtd. in “Tires” 37). Kaprow, like Rosenquist, placed common objects in new contexts in an effort to destabilize the viewer, provoking a potentially hostile reaction from his audience. Kaprow said, “I have photographs from that [1961] show, and everyone has this incredibly tentative look on his face” (qtd. in “Tires” 37). He created another installation of tires outside a German shopping mall that was vandalized.

[13] The U.S. Air Force logo superimposed on the mushroom cloud, icon of the Cold War, mocks corporate assurances and blind loyalty to brand names such as Firestone (Hales). Cover Girl, as feminized consumer, need not worry about nuclear war; rather blind faith in the armed services will ensure the appropriate response to communist incursion, even at the cost of mutually assured destruction. Yet Cover Girl, brainwashed by advertisers, corporations, and the U.S. government, also participates in this process by using her body to sell products and ideologies. Rosenquist has endowed Cover Girl with the attributes of the sex symbol: blond hair, coy glance, and red lips. Throughout Rosenquist’s oeuvre, he has associated images of shattered women with consumer goods. Marilyn Monroe I (1962) fragments the sex symbol into red lips, blue eyes, and red-tipped fingernails. These anatomical units, as with the fractured texts of the Coca-Cola logo and the name “Marilyn,” function as powerful inducements to the consumer to buy the product, either the movie star or the soda. Similarly, in Untitled (Joan Crawford Says…) (1964), Rosenquist mocked celebrity endorsements by cropping the brand name and the cigarette from a cigarette advertisement and leaving only Crawford’s face and name, suggesting that the product need not be pictured. In F-111, Cover Girl cheerfully endorses nuclear war, nuclear families, food additives, and the machinations of the advertising industry, despite the potential threat posed by chemicals and bombs. Her body, entangled in technology, represents all women, and all Americans, as mindless drones easily manipulated by the blandishments of advertisers and government alike. Cyborgs both consume, and are consumed, simultaneously.

[14] Yet Cover Girl differs crucially from Rosenquist’s women because she is a child, not a ripe sex symbol such as Marilyn Monroe, and her incorporation raises troubling questions about innocence and experience. What he called “the female form in the picture” is a girl’s head with the blonde hair and red lips of the sex symbol; however she lacks the body that complicates childhood innocence with the promise of future sexual experience. Rosenquist withholds the body, thereby confounding the modern definition of childhood predicted on the eighteenth-century Romantic ideal, because “childhood innocence was considered an attribute of the child’s body, both because the child’s body was supposed to be naturally innocent of adult sexuality, and because the child’s mind was supposed to begin blank,” according to art historian Anne Higgonet (8). He intimates innocence with the white hair ribbons and short bangs, yet the blonde hair and red lips also suggest latent sexuality, as does the hairdryer that can be read as both uterine (hairdryer) and phallic (helmet). The hairdryer/helmet partially shields her from our gaze, just as the suburban home suggested by the well manicured lawn behind her shelters her from harm, yet “[t]he family seems to be a site of psychological conflict as dangerous as any other,” wherein the majority of sexual abuse takes place (Higgonet 223). Moreover, “the belief has become widespread that we live in a contemporary media culture whose images sexualize children, and put children at real and unacceptable risk” (Higgonet 133). Although Higgonet is discussing more recent images, the ease with which Rosenquist’s girl became Cover Girl—“thefemale form in the picture”—suggests that the media culture of the 1960s, which provided the artist with the fodder for his images, also sexualized children. After all, “sensuously attractive children can enhance the image of just about anything,” including bombers and nuclear blasts (Higgonet 157-8).

[15] An advertisement from the July 24, 1964 issue of Time illustrates the extent to which the Cold War had permeated the domestic economy, forging a symbiotic relationship between the female body and technology (fig. 4).

Figure 4

Four images, in surreal juxtaposition, illustrate “The Four Dimensions of FMC”: machinery, chemicals, defense, and fibers and films. The captions purr, “Pool maintenance is simpler…Frosty treats are more tempting…Sea-to-air defense is stronger…Summer fabrics have more flair.” The straight-faced association of missiles with domestic iconography, including the swimming pool, American desserts, and the woman and her three children, asserts the complicity of the domestic sphere, and the homemaker, in the Cold War. The home economist, freed from drudgery by the products provided by FMC, can armor herself in advanced fibroid technology in preparation for her role as an informed consumer of American commodities. She stands on the receiving end of the phallic sea-to-air missile that pointedly indicates her responsibilities on the home front: she must sustain the domestic economy, fill the suburban home with commodities, and raise future cold warriors, here targeted by the missile that both frees them to enjoy their frosty treats and implicates them in the ongoing struggle against communism. Similarly, Cover Girl, as an industrially-engineered technobody, maintains simultaneous identities as daughter, as home economist, as sex symbol, and as jet pilot defending the home front against communist incursion.

Jet-Man

[16] In 1956, William H. Whyte, Jr. published The Organization Man, a critique of the influence of the corporation upon the large number of American males who worked as bureaucrats and scientists for large corporations (including the government and the military), who lived in suburbs, who comprised the largely white, Protestant, migrant, middle class, and who determined cultural norms. Whyte described the Organization Man as one who belongs to the corporation as a cog to a machine. He quoted an I.B.M. executive who stated succinctly “the training makes our men interchangeable” (276). This cyborg sustains his faith in the efficacy of the organization and the “Social Ethic” it promulgates.

[17] Whyte’s description of the Organization Man applies equally well to Reosenquist’s deep-sea diver: “[Organization] Man exists as a unit of society. Of himself, he is isolated, meaningless; only as he collaborates with others does he become worth while, for by sublimating himself in the group, he helps produce a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts” (7-8). The diver’s body is invisible; rather he is a type who is anonymous and replaceable. He negotiates his environment by means of the technology that enables him to see, to breathe, and to navigate the dark waters. And, like the astronaut, the diver explores at the behest of a larger corporation. His mushrooming exhalation replicates the form of the neighboring nuclear blast, implicating him in the manufacture of goods both benign and toxic. In an interview, Rosenquist recognized the engagement of Organization Man in the integrated circuit of defense contracting with specific reference to the manufacture of the F-111: “People are planning their lives through work on this bomber…A man has a contract from the company making the bomber, and he plans his third automobile and his fifth child because he is a technician and has work for the next couple of years” (qtd. in Swenson “F-111” 589-90).

[18] Rosenquist’s depiction of the cybernetic male body speaks not only to the metaphorical relationship between the male body and technology, but also to the material linkages established by science, principally military science. The rigid, phallic profile of the jet conjures the technobody of the Jet-Man. The electrical systems of the jet enmesh the body in order to supplement human reaction times rendered obsolete by supersonic speed. Popular literature recognized the new relationship between the pilot and the aircraft forged by technology. In Fail-Safe, General Bogan, standing in the war room of Strategic Air Command in Omaha, reminisces about the old days, when pilots, like cowboys, were heroes who prevailed despite the limits of technology: “It had taken…a long time to forget the old familiar smells of airplanes. These were the muscular and masculine odors of great engines, the kerosene stink of jets, the special private smell of leather and men’s sweat which hung in every pilot’s cockpit” (35). Roland Barthes described the new relationship between pilot and technology in “Jet-Man”: “The jet-man is a jetpilot…he belongs to a new race in aviation, nearer the robot than to the hero” (71). Jet-Man, unlike the pilot-hero nostalgically evoked by General Bogan, labors at the behest of aviation technology. No longer cowboy but cyborg, Jet-Man operates at the conjunction of human and machine.

[19] Both Jet-Man and the F-111 belong to the integrated circuit of the military-industrial complex. John F. Kennedy’s Secretary of Defense, Robert Strange McNamara, applied corporate management techniques to the military, including the F-111 program. McNamara numbered among Kennedy’s “whiz kids,” men appointed to fill cabinet and administrative positions on the basis of their intelligence and their experience in the corporate sphere, regardless of party affiliation or prior experience with either government or the specific demands of the position. Kennedy hoped to increase governmental efficiency by deploying the quantitative approach to problem solving popular in corporations (Kinzey 4). Robert McNamara typified the whiz kid. He had been a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army during World War II, president of Ford Motor Company, and had little experience with foreign affairs, security issues, and military administration (McNamara 208-9). Although the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962) demonstrated the potential of the brain trust to solve diplomatic problems, the F-111 project exemplified the failure of Kennedy’s whiz kids to apply corporate management techniques to military operations.

[20] McNamara developed the concept of “commonality,” positing that the development of an all-purpose jet for use by both the Navy and the Air Force would increase efficiency and lower costs (Art; Coulam; Kinzey; Logan). In February 1961, McNamara delayed development of a pre-existing Air Force project to develop a close-air-support aircraft, the Tactical Fighter Experimental (TFX), and asked the Air Force and the Navy to redevelop this project into an all-purpose, all-weather nuclear bomber that would meet both services’ requirements. Scandal, mismanagement, and a congressional investigation marked the development of the TFX, renamed the F-111 “Aardvark” in December 1961. Although McNamara claimed that the F-111 could perform the tasks of transport, bomber, and fighter pursuit plane, it could fulfill none of these requirements as well as bombers, transports, and fighters already in service. Design, performance, and management problems plagued the subsequent development of the Air Force’s F-111A, including crashes during test flights due to engine stalls. The Navy cancelled the F-111B when design problems reduced the commonality between Air Force and Navy versions of the F-111 to less than thirty percent, and the F-111B failed to meet Navy requirements for low aircraft weight. The Air Force’s F-111A fared little better. Although the F-111A went into production and first flew on February 12, 1967, only 158 F-111As were built, including developmental models. The F-111 neither demonstrated the value of commonality nor did it meet military requirements. In this instance, the merger of the corporate and military spheres failed to produce a workable war machine.

[21] Swenson identifies Rosenquist’s image as “the new Air Force fighter-bomber” (“F-111” 589), implying that F-111 depicts the F-111A. Many authors have made ahistorical claims that Rosenquist intended F-111to criticize the U.S. presence in Vietnam. In 1964, when Rosenquist initiated F-111, the F-111 project was entering its extended test-flight phase and the U.S. had not yet mounted large-scale, overt operations in Vietnam. The U.S. rapidly increased its presence in Vietnam in 1965 after the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. The majority of Americans regarded the war favorably until the Tet Offensive (1968). Though General Dynamics had produced the first developmental model of the F-111A in 1964, the F-111A entered active service only in 1967. The Air Force had planned the F-111 as a long-range, nuclear bomber intended to counter Soviet aggression in Western Europe; however, the F-111 was deployed in Vietnam in 1972, seven years after Rosenquist had completed F-111. Works of art accrue meaning over time, however, and many writers have subsequently claimed that F-111 critiqued the American presence in Vietnam. In 1992, Rosenquist stated that F-111 “had a number of ideas about art and life and a little bit about the war in Vietnam, but not too much. People took it for a big, antiwar painting. I protested against the war and later, in 1972, I even spent a night in jail. But the painting was more about peripheral vision. I thought it was very peculiar to be an artist, it was a joke, because society was so much stronger” (qtd. in Bonami 102).

[22] Robert Coulam has attributed the failure of the F-111 program to a “cybernetic paradigm” of decision-making. The cybernetic paradigm, as opposed to the analytic paradigm, assumes irrational choices made by and for essentially independent subsystems coordinated in an organizational hierarchy. (Coulam’s cybernetic paradigm of decision-making institutionalizes hierarchy, while Haraway’s manifesto imagines a cybernetic system without gender in order to free women from patriarchal hierarchies.) Organization Man, as servomechanism, “[acts] routinely on the basis of simplified images of complex problems, oblivious to the results of [his] efforts except insofar as the simplifications themselves are implicated” (Coulam 17-8). McNamara, as a cog in the Cabinet subsystem, and Jet-Man, conjoined with the F-111, both function as servomechanisms in the military-industrial complex: each makes decisions based on a radically simplified understanding of the impact of his decisions upon the larger organization and the environment.

[23] Both the composition and the structure of Rosenquist’s F-111replicate the cybernetic paradigm, which emphasizes “the routine pursuit of unintegrated, and often conflicting, goals by a highly fragmented decision process” (Coulam 6). The fragmented composition creates a series of highly independent subsystems organized within the framework of the support, which in turn implicates the larger gallery economy. F-111 consists of 51 panels, originally intended to be sold separately (Swenson “F-111” 596-7; Scull; Goldman 42-3). Rosenquist describes the subdivision of both the support and the image of F-111 as “a dark joke,” because the collector who purchased a panel from F-111 also acquired a souvenir of a weapons system procured with his or her tax dollars (qtd. in Siegel 34). Both subdivision and iconography force the collector to realize his role as a tax-paying cog in the integrated circuit of the political economy. When Robert Scull purchased the entire work in 1965, Rosenquist commented that a collector as rich as Scull had probably paid enough taxes to purchase a few F-111s, and now Scull would have a memento of his role in the weapons acquisition process (Goldman 42).

[24] The alienation and the loss of autonomy occasioned by the cybernetic operations of bureaucratic organizations rendered Organization Man both an object of sympathy and a threat. Housewives routinely praised the autonomy offered by a career in homemaking, contrasting that freedom with the strictures of Organization Man’s position within a managerial hierarchy (May 20-2). For Organization Man, the domestic sphere provided both a refuge from bureaucratic life and a context for the display of commodities purchased with his salary. Yet his isolation as a subsystem within the corporate body also offered the possibility of autonomy and resistance. Whyte described the individual who could subvert the organization versus one who functioned as an unheeding cog:

The organization people who are best able to control their environment rather than be controlled by it are well aware that they are not too easily distinguishable from the others in the outward obeisances paid to the good opinions of others. And that is one of the reasons they do control. They disarm society (11).

Numerous Cold War narratives center upon this theme of the potential threat to society posed by an Organization Man gone wrong, a threat borne of the literal and the metaphorical conjunction of the male body with technology. Dr. Strangelove (1963), Red Alert (1958), and Fail-Safe (1962) all concern the loss of societal control over servomechanism, over sentient technology, over Jet-Man. In Haraway’s words, “modern war is a cyborg orgy” (174).

Jet-Man meets Cover Girl at the F-111

[25] A series of three articles about Rosenquist and F-111 in theMetropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin for March 1968—occasioned by the controversial exhibition of the work at the Museum—position Rosenquist, and Pop art, as the legitimate heir of Jackson Pollock and Abstract Expressionism (Geldzahler; Scull; Swenson “Interview”; Tillam; Hoving). A photograph by Hans Namuth captured Rosenquist at work, violently gesturing at the canvas surrounding him (fig. 5).

Figure 5

Lest the reader miss the reference to action painting, the cover to the Bulletin offers a disorienting detail ofF-111 excised from the field of spaghetti, its figuration dissolved into the luscious blur of color and the eloquent trace of gesture, albeit a gesture made with an airbrush. Another photograph squeezes the artist between the words “U.S. AIR FORCE” and his Cover Girl. Rosenquist’s expression of grim determination and blatantly political iconography cast the artist as penseur, a wry observer of the foibles of a decadent culture.

[26] Rosenquist, as penseur, makes a seemingly uncharacteristic political statement with F-111. Rosenquist customarily selected “anonymous images,” images neither old enough to evoke nostalgia nor new enough to incite passion (qtd. in Swenson “What Is Pop Art?” 41). To deploy “the newest, latest fighter-bomber at this time, 1965” as the scaffold of his composition marks a departure from neutrality, from expendable images, from “no image, nothing image, nowhere” (qtd. in Swenson “F-111” 589; qtd. in Siegel 30). Describing the genesis of F-111, Rosenquist explains that he “started out without an imagery at all,” but that in the wake of the assassinations and the Democratic National Convention, “politics and life” had intruded upon his work: “I was very angry too at that time and with F-111…anger came into my mind” (Siegel 33). At critic G. R. Swenson’s behest, Rosenquist recounts his personal associations with each image incorporated into the composition. However, when asked to reveal his motivation for the whole, rather than the parts, Rosenquist retreats behind a wall of anecdote:

I think of [F-111] like a beam at the airport…All the ideas in the whole picture are very divergent, but I think they all seem to go toward some basic meaning…[toward] some blinding light, like a bug hitting a light bulb…The painting is like a sacrifice from my side of the idea [about technology] to the other side of society…this picture is…a fragment I am expending into the boiler (qtd. in Swenson “F-111” 590-5).

Although the artist’s verbiage offers slight insight into “some basic meaning,” his imagery bespeaks his intention both to identify and to critique the consumer’s role in the military-industrial complex, but he refuses to explicate this content. He describes the ideas he has incorporated as bugs hitting a light bulb, making a fiery sacrifice on the altar of technology. In this context, the light bulbs become tools of the angry artist, who attempts to light the path to reason by assembling images that critique the consumer’s complicity in the military-industrial complex. The cracked light bulb suggests the futility of his heroic effort.

[27] Rosenquist constructs his critique from fragments, stating that “the relationships may be the subject matter, the relationships of the fragments I do. The content will be something more, gained from the relationships” (qtd. in Swenson “What Is Pop Art?” 63). In F-111, formal relationships between objects fragmented and juxtaposed reveal sinister connections between the hard, masculine technology of the war machine and the soft, feminine technology of the home appliance. The globular shape of the light bulb situated below the Air Force emblem replicates the silhouette of the star and bars, thereby reminding the viewer that General Electric and Westinghouse not only manufactured consumer goods, but also served as defense contractors. Similarly, the juxtaposition of the F-111 and the angel food cake concretizes another connection between domestic and military spheres. Although the military initially developed cake mixes for field use, Pillsbury adapted and marketed cake mix as a convenience product (Miller). The annular shape of the angel food cake, replicating that of the Firestone tire, alludes to the industrial source of the homey product, a product that appropriated the homemaker’s role under the guise of convenience (Mamiya 129-30).

[28] Corporations used advertising, as well as manufacturing, to forge links between the military and the domestic spheres. Numerous advertisements from Time demonstrate that corporations used defense contracts to promote their consumer products. A Union Carbide advertisement from September 11, 1964 asks, “Is it fact that a leader in nuclear research has a hand in bringing music to the Wilkies’ family picnic?” Subsequent text touts the diversification that enables a single corporation to both lead the field in atomic energy and manufacture the Eveready batteries preferred for portable radios. Similarly, an advertisement from July 17, 1964 boasts, “In the air or outer space…Douglas gets things done!” Images and text inform the reader that Douglas not only manufactures jetliners for commercial aviation, but also explores advanced missile techniques for “air-to-air, air-to-ground, ground-to-air and ground-to-ground missions.” Both Douglas and Union Carbide predicate their propaganda upon the assumption that what pleases the military will delight the American family.

[29] Although Rosenquist’s medium resembles that of the advertiser, his message differs dramatically. Corporations assured the consumer that defense contracts yielded not only weapons systems for national security, but also domestic technology of the same degree of reliability, endurance, and sophistication. Rosenquist mocked these guarantees by placing the F-111 within the context of consumer culture where planned obsolescence insures continued consumption. By 1964-5, government hearings, ongoing scandal and continuous press coverage had exposed the F-111 project as a model of government waste, ineptitude, and corruption. Pairing the nuclear bomber with a constellation of domestic appliances equates military consumption of the F-111 with domestic consumption of ephemeral products such as food energy and light bulbs.

[30] Rosenquist’s juxtaposition of the military jet with symbols of domestic consumption not only ridicules governmental claims of efficiency through commonality, but also criticizes the consumer’s participation in the military-industrial complex. The Kitchen Debate underscored the consumer’s patriotic duty to maintain the commodity gap through consumption. Both government and consumer purchased goods from American conglomerates, fueling research and development of products for both sectors. Just as the F-111 protected the American consumer from Soviet military aggression, so consumption of the F-111 defended the capitalist economy against state socialism. Rosenquist inserts F-111 into the capitalist economy as both a commodity and a souvenir of consumption. Consumption ofF-111 implants the purchaser in the integrated circuit of the military-industrial complex. The F-111 emblazoned upon both canvas and aluminum panels reminded the purchaser of his roles as both tax-payer and consumer, while the nuclear blast whose shape resonates throughout the composition derided governmental assurances that consumption will protect the American way of life.

[31] Rosenquist’s disclosure of the consumer’s role in the military–industrial complex reinforces assumptions about gender roles and consumption. The jet and the hairdryer, focal points of the composition, epitomize gendered technology. The phallic jet embodies masculine military technology, a technology predicated upon explosive thrust, speed, and raw power. In contrast, the hairdryer, as domestic technology, accommodates, and even replicates, the body of the woman entrusted with promoting the domestic economy through the consumption of home appliances. While the hairdryer/helmet suggests that the girl could be the pilot, its function as an appliance associated exclusively with female beautification belittles the notion that a woman could fly a jet. Rather, Jet-Man partners Cover Girl in an orgy of consumption and sustains the gendered hierarchies that Haraway sought to dismantle.

[32] Despite Rosenquist’s affirmation of the artist’s role as cultural commentator, F-111 presents a paranoid, even sexist, vision of bodies and technology. Alice Jardine, in an analysis of possible responses to cyborg theory as a political maneuver, identifies men and women who want science and its handmaiden, technology, to liberate man from woman, especially through reproductive technologies intended to drain the female human body of its procreative powers. The male technician replaces the female body with feminized machinery and endows his creation with the qualities of either virgin or vamp (151-2, 156-7). Rosenquist, as technician, asserts the procreative rights of the male artist by emasculating the female reproductive system. He has sliced open the vaginal angel food cake, cracked open the uterine light bulb, and fragmented the cervical tire. Cover Girl, both prepubescent virgin and cybernetic vamp, exudes the sterile sexuality of the feminized machine.

[33] Despite Rosenquist’s claim to a demiurgic role as the progenitor of cybernetic offspring, his body is enmeshed in F-111. A second look at Namuth’s vision of male (pro)creativity reveals Rosenquist wielding the airbrush as a mechanical phallus (fig. 6; note that the photograph reproduced here is another in the series taken by Namuth rather than the more dramatic photograph published in the Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin).

Figure 6

Rosenquist stands on a chair, leaning back to view his progress, holding the airbrush in his hand. Namuth’s first photograph of Rosenquist shows him in a blur of action, physically attacking the canvas with his hands. The second, still image reveals that Rosenquist’s action painting is achieved with a mechanized tool that renders him bionic. While Pollock needed only the energy of his masculine arms to throw paint, Rosenquist requires electricity to power his picture-making. The sequence of images in F-111 enacts cybernetic sex as the mechanized ejaculation of nuclear waste. The tumescent hairdryer presages the nuclear explosion that thrusts into the receptive umbrella. A second ejaculatory exhalation, issued by the diver, quickly follows. In the orange-lit afterglow, the narrowing jet-nose lingers over the spent strands of spaghetti, while the labial folds of the aluminum drop cloth, like a cybernetic vamp, catch the painterly drops of male procreativity. The aluminum panel, like a deflowered mechanical bride, discloses the stenciled traces of consummation. Rosenquist, like Adam, models life from his bodily materials. He alone fathers Cover Girl and Jet-Man, asserting his reproductive sufficiency.

[34] The scale of F-111—at eighty-six feet, it is thirteen feet longer than the military jet—makes a second claim for the power of male procreativity. Rosenquist recounts his feeling of powerlessness before the large billboard advertisements he fashioned as a commercial artist: “I felt this numbness that comes from being a tool that sells the products” (qtd. in Goldman 102). F-111, as an installation, similarly seeks to overwhelm the viewer with the engorged products of American consumer culture. Rosenquist stated:

The F-111 was enclosed—four walls of a room in a gallery. My idea was the make an extension of ways of showing art in a gallery, instead of showing single pictures with wall space that usually givens your eye a relief. In this picture, because it did seal up all the walls, I could set the dial and put in the stops and rests for the person’s eye in the whole room instead of allowing the eye to wander and think in an empty space. You couldn’t shut it out, so I could set the rests (qtd. in Swenson “F-111” 595).

F-111 enfolds the viewer, disallowing space for another reality, another reading. F-111 has been installed upon as many as four walls and as few as one. Each multi-wall installation bends the image, creating critical junctures where objects confront each other and visual effects converge. Rosenquist observed:

At the [Castelli] gallery the hurdle was presented in two perpendicular halves because it came at the corner of the room. The hurdle was broken right down the center. On the left are a couple of aluminum panels so that the right side, which is superimposed on the painted areas, reflected around the corner into the aluminum and it appeared that there was another piece of the hurdle. In the gallery it looked as if the runner would have to junk a triangular hurdle, or one with several alternatives, but they were blind alternatives because the hurdle was in a corner. The runner seemed to hurdle himself into a corner (qtd. in Swenson “F-111” 597).

Rosenquist uses scale, fragmentation, juxtaposition, and reflection to dominate the viewer. The aluminum panels incorporate the spectator by means of reflection, yet the enlarged products of the military-industrial complex resist the human body as the measure of scale. Everyday objects engage the onlooker, only to repulse familiarity with enlarged and excruciating detail. This experience typifies “homes for cyborgs,” where “[o]bjects now act out beyond their proper domains…all connected in ways that should not be, in order to reveal their sinister interdependence in the domestic system” (Vidler 161).

[35] F-111 sustains traditional gender roles in the technological age, despite Donna Haraway’s “ironic political myth” of genderless cyborgs. Cover Girl, with her blonde hair and red lips, gathers under her hairdryer housewife, home economist, mother, daughter, and feminized consumer of Cold-War culture. Even with her helmet, she can only play at the war games undertaken by Jet-Man, who as a cog in the corporate, institutional machine of the military-industrial complex simultaneously threatens and protects the domestic sphere. The artist, shopping for images amidst the visual abundance of Cold War culture, has fashioned an apocalyptic panorama that makes an ironic statement about the consumer’s complicity in the military-industrial complex. He also created a “megamachine” that, like its namesake the F-111, is an “enormous machine where the human becomes an indispensable part of a larger mechanical complex…There the body is turned into a micromachine or automaton in order to fit into the larger mechanical structure” (Jardine 158). When experienced as an installation, F-111, as megamachine, constitutes the viewer as micromachine, an automaton subsumed within the larger mechanical structure.

[36] Although Rosenquist may have intended his chef d’oeuvre as a “dark joke,” his procreation of cyborgs invites the application of gender theory that exposes not only the artist’s assumption that gender roles are fixed, but also makes possible the subversion of that paradigm. Although neither Haraway nor Vidler discuss F-111, their mythic imaginings suggest that by conjoining human and machine, Rosenquist created cyborgs that transcend the gender roles reinforced by mid-century American material culture. The cyborg obviates traditional definitions of gender, which are predicated upon the human body. Cover Girl, as pilot, suggests that any body, merged with machine, can overcome gender; while Jet-Man, as deep-sea diver, manifests no gendered characteristics as he sinks into the gloomy depths. Both lack bodies, rendering them figureheads in the most literal terms. Without bodies, Rosenquist’s cyborgs are free to colonize cyberspace, which, according to “A Declaration of Independence for Cyberspace,”

consists of transactions, relationships, and thought itself, arrayed like a standing wave in the web of our communications…a world that is both everywhere and nowhere, but it is not where bodies live…Your legal concepts of property, expression, identity, movement, and context do not apply to us. They are all based on matter, and there is no matter here (Barlow).

In cyberspace, perhaps, Cover Girl and Jet-Man can slip the surly bonds of earth and touch a genderless future.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Ann Kibbey and the anonymous readers for their constructive comments. Thanks especially to Christine Poggi, University of Pennsylvania, and Christopher Reed, Lake Forest College, who first heard this paper in their seminar at the University of Pennsylvania and made many thoughtful comments that moved the paper toward publication. I also want to thank Christopher Studabaker, who enhanced the three advertisements reproduced from microfilm. Many people assisted me with obtaining photographic permissions, especially Art Resource, Peter Namuth, and the Center for Creative Photography.

Works Cited

- Art, Robert J. The TFX Decision: McNamara and the Military. Boston: Little, 1968.

- Barlow, John Perry. “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.” 8 February 1996. http://homes.eff.org/~barlow/Declaration-Final.html. Accessed 27 June 2006.

- Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. Trans. Annette Lavers. New York: Hill and Wang, 1957.

- Bonami, Francesco. “James Rosenquist: Militant Pop.” Flash Art25.165 (Summer 1992): 102-4.

- Bryant, Peter. Red Alert. New York: Ace, 1958.

- Burdick, Eugene and Harvey Wheeler. Fail-Safe. New York: McGraw, 1962.

- Coulam, Robert F. Illusions of Choice: The F-111 and the Problems of Weapons Acquisition Reform. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1977.

- Fleissner, Jen. “The Daughters of Frankenstein.” Women’s Review of Books Sept. 1996: 20+.

- Geldzahler, Henry. “James Rosenquist’s F-111.” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 26.7 (March 1968): 277-81.

- George, Peter. Dr. Strangelove, or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. 1963. Oxford: Oxford U P, 1988.

- Goldman, Judith. James Rosenquist. New York: Viking, 1985.

- Hales, Peter B. “The Atomic Sublime.” American Studies 32.1 (Spring 1991): 5-31.

- Haraway, Donna. “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s.” Rpt. in Coming to Terms: Feminism, Theory, Politics. Ed. Elizabeth Weed. New York: Routledge, 1989. 173-204.

- Higgonet, Anne. Pictures of Innocence: The History and Crisis of the Idea of Childhood. London: Thames & Hudson, 1998.

- Hook, Sidney. The Fail-Safe Fallacy. New York: Stein and Day, 1963.

- Hopps, Walter and Sarah Bancroft. James Rosenquist: A Retrospective. New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2003.

- Hoving, Thomas. Making the Mummies Dance: Inside the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Simon, 1993.

- Jardine, Alice. “Of Bodies and Technologies.” In Discussions in Contemporary Culture. Ed. Hal Foster. Seattle: Bay P, 1987. 151-8.

- Kaprow, Allan. “The Coutyard.” In Happenings: An Illustrated Anthology. Ed. Michael Kirby. New York: Dutton, 1965. 105-117.

- Kinzey, Bert. F-111 Aardvark. Rev. ed. Detail & Scale Series 4. Blue Ridge Summit, PA: Tab Books, 1989.

- Logan, Dan. General Dynamics F-111 Aardvark. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Military History, 1998.

- Lupton, Ellen. Mechanical Brides: Women and Machines from Home to Office. New York: Princeton Architectural P, 1993.

- Mamiya, Christin J. Pop Art and Consumer Culture: American Super Market. Austin: U of Texas P, 1992.

- May, Elaine Tyler. Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era. New York: Basic, 1988.

- McNamara, Robert S. Out of the Cold: New Thinking for American Foreign and Defense Policy in the 21stCentury. New York: Simon, 1989.

- Miller, Marilynn. “Variety into the Mix.” Philadelphia Inquirer 10 May 1995: F1+.

- Packard, Vance. The Hidden Persuaders. New York: Washington Square P, 1957.

- Scull, Robert C. “Re the F-111: A Collector’s Notes.” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 26.7 (March 1968): 282-3.

- Siegel, Jeanne. “An Interview with James Rosenquist.” Artforum 10.10 (June 1972): 30-4.

- Stich, Sidra. Made in U.S.A.: An Americanization in Modern Art, the ‘50s & ‘60s. Berkeley: U of California P, 1987.

- Swenson, G. R. “F-111: An Interview with James Rosenquist.”Partisan Review 32.4 (Fall 1965): 589-601.

- Swenson, G. R. “An Interview with James Rosenquist.” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 26.7 (March 1968): 284-8.

- Swenson, G. R. “What Is Pop Art? Part II” Art News 62.10 (Feb. 1964): 40+.

- Tillam, Sidney. “Rosenquist at the Met: Avant-Garde or Red Guard?”Artforum 6.8 (April 1968): 46-9.

- “Tires.” New Yorker 8 Oct. 1984: 37-8.

- Varnedoe, Kirk and Adom Gopnik. High & Low: Popular Culture and Modern Art (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1990.

- Vidler, Anthony. The Architectural Uncanny: Essays in the Modern Unhomely. Cambridge: MIT P, 1992.

- Whyte, Jr., William H. The Organization Man. New York: Simon, 1956.

- Photo Credits

- Figure 1 James Rosenquist (b. 1933). _F-111_. 1964-65. Oil on canvas with aluminum. 10′ x 86′ overall. Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hilman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). (00473.96a-w). Art (c) James Rosenquist/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Reproduction of this image, including downloading, is prohibited without written authorizeation from VAGA, 350 FIfth Avenue, Suite 2820, New York, NY 10118. Tel: 212-736-6666; Fax: 212-736-6767; email: info@ vagarights.com.

- Figure 2 Sugar Information, Inc. advertisement from Time, 17 July 1964.

- Figure 3 The Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company advertisement from Time, 17 July 1964.

- Figure 4 FMC Corporation advertisement from Time, 24 July 1964. Reproduced with permission of FMC Corporation.

- Figure 5 Hans Namuth, photograph of James Rosenquist at work onF-111, 1965. Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona © Hans Namuth Estate.

- Figure 6 Hans Namuth, photograph of James Rosenquist at work onF-111 with an airbrush, 1965. Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona © Hans Namuth Estate.