Beauty, Desire, and Anxiety: The Economy of Sameness in ABC’s Extreme Makeover

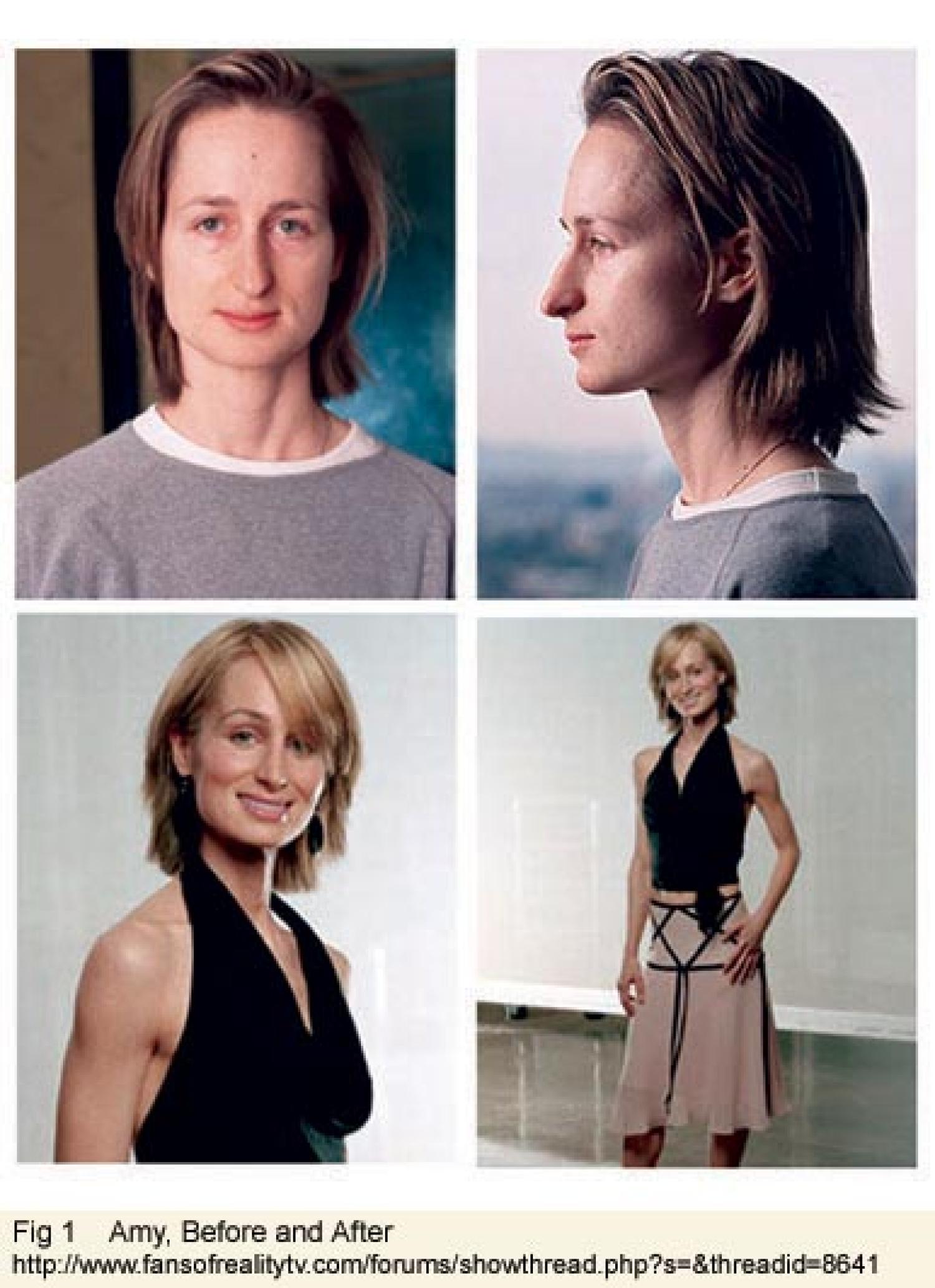

[1] In a 2003 episode of Extreme Makeover, ABC’s makeover show offering transformation through style advice and multiple plastic surgeries, Amy, a “painfully shy 29-year-old cake decorator from Indiana,” exclaims in her post-makeover interview, “I’m me now! I don’t have to listen to what anyone else says” (Season 1- Episode 3, per epguides.com).

Figure 1

[2] Amy’s words suggest that pre-makeover insecurity caused a split between her sense of identity and her physical presence, exacerbated by a social censure that diminished her self-worth. Like many victims of trauma, Amy responded to pain through dissociation, separating her sense of identity from her embodied experience, in many ways mirroring what theorists identify as the postmodern condition. After surgery Amy claims a unity of identity and body, a sense she has finally become herself, thus believing she has also transcended societal censure and can exercise complete autonomy, allowing her to ignore all cultural mandates. The Extreme Makeover procedures—a nose job, extensive reconstructive dentistry and porcelain veneers, bags removed from beneath her eyes, breast implants, hair styling and coloring, make-up and fashion lessons—offer Amy a classical sense of the subject, one that is internally coherent and fully autonomous; she feels fractured no longer, a new-found state that strikes her as liberating and empowering.

[3] Rectifying the postmodern divide is quite a promise, even for the hyperbole of reality TV, but Extreme Makeover offers this and more. (For general analyses on reality TV, see Home and Jermyn, Murray and Ouellette; for helpful discussions on plastic surgery’s rise in American culture, see Haiken, Blum, Gilman, Davis). Participants in the show claim both coherent subjectivity and new modalities of power. Yet, in trying to reassure us that it can eradicate embodied anxieties, Extreme Makeover also manages to pointedly remind us of those very flaws, thus exacerbating both anxiety and desire and promising relief only through “beauty.” And here, it’s important to make clear that the sort of attractiveness espoused by Extreme Makeover, and other popular culture makeovers more broadly, is a “beauty by the numbers” that can be calibrated and imposed by surgeons and clever makeup specialists. Though Extreme Makeover rhetorically gestures to “inner beauty,” it clearly codes internal attractiveness as dependent upon external appearance.

Figure 2

[4] What we’re seeing in both Extreme Makeover and the present media and makeover genre more broadly, then, is not programming dedicated to individuated enhancement, but a clustering of makeover shows working to underscore collectively the imperative of high-glamour appearance—golden highlights, trimmed bodies, four-inch heels, and double D breasts notwithstanding. There are, at this writing, approximately nineteen home and body (and now car) makeover shows on the air. Of these, it is the programming centering on appearance and the body that most concern me: What Not to Wear (both TLC and BBC),Nip/Tuck (F/X), A Makeover Story (TLC),Dr. 90210 (E!), A Complete Story (TLC), Plastic Surgery, Before and After (Discovery), Made (MTV), I Want A Famous Face (MTV), Head 2 Toe (Lifetime), The Swan (Fox) and, of course, Queer Eye for the Straight Guy (Bravo, NBC) and its parody, Straight Plan for the Gay Man (Comedy Central).

Figure 3

[5] In this mix, Extreme Makeoverhas become a “standard bearer,” its influence traceable throughout other media, as documented by, for instance, the random use of the words “extreme makeover” in America’s ubiquitous Sunday supplement, Parade (see the March 28, 2004 issue), a front-page star exposeé, several “family” comics, and the promise of an “Extreme Makeover Here in Indianapolis”. A commercial for Pantene shampoo features Kelly Ripa who relies on her “extreme makeover in a bottle.” America’s popular culture Bible, People, ran a November 2003 cover celebrating “real-life Extreme Makeovers;” People also reported at Oscar time that Catherine Zeta-Jones stalled in leaving the

Figure 4

Figure 5

But SNL was supplanted soon after when I received e-mail SPAM luring me with promises that I could “win an extreme makeover or $50,000 in cash!” To be SPAMed strikes me as indisputable evidence of cultural saturation.

[6] Given this, it seems safe to say that Extreme Makeover’slanguage and concepts have entered a common cultural discourse, aided and abetted by the fact that its primary locus of control is the body itself. Since the body evokes our collective desires and anxieties, I believe it’s possible to achieve a more nuanced sense of our broader cultural investments by putting Extreme Makeover under the same sort of analytical gaze endured by its participants.

Figure 6

Ultimately, I argue thatExtreme Makeover offers viewers the promise of the exceptional (coded as high-glamour beauty) built on an economy of sameness. In effect, the show exploits the same bodily anxieties that fuel the psychic pain it ostensibly cures, offering makeover participants and home viewers a contradictory pairing—the despair of anxiety, the (promised) joy brought by beauty. To salve the wounds of this contradiction, we are offered a form of beauty-by-the-numbers that is narrow, formulaic, and dependent on the very cycles of anxiety and desire it promises to transcend.

Body Scan: Extreme Makeover’s Place in the Genre

[7] Let me begin by saying that Extreme Makeover is a show very easy to dislike (and thus to dismiss). With its rigidly formulaic structure, its heavy-handed and melodramatic male voiceover, its insistence on physical beauty as the only standard for self worth, its deification of plastic surgery and surgeons, its encouragement of voyeuristic indulgence, its almost exclusive fixation on female bodies, its perpetual overwriting of race and class signifiers, and its relentless endorsement of heterosexual relationships,Extreme Makeover seems like just another one of television-land’s productions that pander to the latest fad. And make no mistake, it is. Extreme Makeover is also a resonant text that speaks volumes about media culture, the signification of beauty, desire, social power, modes of gender, and pleasurable narratives.

[8] The story it tells—one of suffering and transformation, of desperation and joy—is as old as narrative itself. We can see elements of Extreme Makeover’s story played out in myth cycles of death and renewal, in fairytales that depict the heart’s desire and the body’s change, in operas, novels, films, and television where suffering is interrupted by a benevolent spirit (be it fairy godmother, good witch, or plastic surgeon) who brings hope, revitalization, and opportunity for a newly lived life. In terms of provenance, we might as easily point toDracula as to Now Voyager! (two very different sorts of makeover narratives) to understand the fascination of the changing and changeable body’s relation to the psyche. The fact that Extreme Makeoveris a televised text, of course, links it to important forbears, such as Queen for a Day, which searched for sad stories, put them on display and rewarded each Queen’s long-suffering. Yet, there is a significant difference between a new washing machine and a new nose, and if we are to look to television antecedents to better understand Extreme Makeover, I believe we’d be more likely to find them in an amalgam of soap opera and game show, say General Hospital and The Price is Right, where sad stories are the only sorts of stories worth telling, where consumer knowledge is assessed and rewarded, where benevolent hosts select from a pool of candidates to “come on down,” and where audiences vicariously participate in the tension and celebrate the outcome—be it love in the afternoon or winning the grand showcase.

[9] For the particular makeover shows presently on the air, the premise is simple: alteration equals entertainment. The sub-text is more complicated, for the process makes clear that personal transformation is the first and most necessary step in self-improvement and, thus, to a sort of sublime American entitlement. Makeover shows celebrate a teleology of progress, represented as empowerment, positive self-esteem, and a winning personality, all purchased through the currency of narrowly defined beauty. The genre also offers a version of novelty: new beginnings that promise new stories, new sorts of passions no longer undercut by shame. The promise of novelty seems a promise of fascination—a body, a mode of presentation, a haircut that will assure lasting interest. The disdain for “letting oneself go” requires that makeovers be a constant “necessary thing.” Looks must be freshened, updated. Hair needs cutting. Spray-on tans only last four days. Hair extensions, two months. Botox, four months (if you’re lucky). The commitment to continual makeovers propels a necessary consumerism. In other words, buying into requires buying. Adopting the makeover regime means committing oneself to consistent and long-term purchases of style, beauty products and cosmetic procedures. As if to demonstrate this very idea, ABC’sExtreme Makeover website offers physician referrals for people considering plastic surgery, though ABC clarifies that web links are not part of their official website (abc.go.com/primetime/extrememakeover/index.html). It should be noted, however, that the rise of beauty as a consumable commodity has historical links to women’s increased purchasing power and greater presence in the non-domestic marketplace after World War II. Indeed, there is an intricate interconnection between consumption and American womanhood stretching at least to the eighteenth century and allowing for what Jane Gaines has called the “glimmer of utopia” (Gaines 11, see also Haiken, Merish, Radner). As such, the plethora of cosmetic options now available to both men and women link directly to women’s influence on the consumer market (and its consequent skewing toward “women’s” values), suggesting that “buying into” is a polyvalent sign on a continuum where lies both agency and subjugation.

[10] In addition to increased spending, makeover logic also requires putting oneself firmly under an internalized monitoring gaze that is diligent about reminding the body that it needs maintenance and variety in its presentation (an interesting form of mind/body split in itself). Because of this, there is a strain of compulsory normalcy underscored through makeover programming that allows for no conscientious (or lazy) objectors unwilling to expend money or energy in support of appearance. Following this logic,Extreme Makeoverreinforces the very sorts of social stigma that seem to fuel the need for the show—the pain of not fitting in, the judgment for being overweight, malformed, or un-pretty. Here is the makeover ultimatum: if you can change, you should; if you refuse to change, you deserve whatever consequences come your way. In many ways, this attitude parallels what Susan Bordo observes in the cultural policing of the slender body. Speaking of obese persons who “claim” to be happy, Bordo channels a societal voice that complains, “If the rest of us are struggling to be acceptable and ‘normal,’ we cannot allow them to get away with it; they must be put in their place, be humiliated, defeated” (203).

[11] On Extreme Makeover, where transformation is not just about surfaces but about the body itself, social censure functions as a way to legitimate the need for aesthetic surgery. In turn, these pressures—manifested in humiliation, self-consciousness, self-loathing—are held up as the necessary (and just) consequences to resisting alteration. The reasoning creates a moralistic double-bind. You’ll feel bad if you don’t and worse if you won’t, all of which you’ll deserve. Capitulating to the body/beauty ideal stands as the only form of relief from that ideal, suggesting, quite enigmatically, that the way out of the maze is to go deeper into it. It’s this sort of puzzling logic that underscores Amy’s statement starting my essay. “Plain” Amy believes that finally achieving a cultural standard of “glamorous” beauty offers her “herself,” and thus the power to transcend the very standards that compelled the change.

[12] At first consideration, her statement seems patently false, or at best, oxymoronic. It doesn’t make sense that one can establish authority over hegemonic values by giving in to those values. Yet, in a twentieth-century image-centered culture, such as ours, perhaps no statement is more valid. From Walter Benjamin to Stuart Hall, theorists note that the rise of imagistic technology has made the twentieth century—and now the twenty first—the most visually dominant epoch ever. Films, television, advertising and other mass-produced images—all contribute to the “empire of images” that one must negotiate in making meaning and understanding identity. But the empire of images also incorporates a degree of reflexivity, particularly in relation to the body. So, as Kenneth Dutton puts it, in our postmodern culture, the body not only carries the message, it is the message (177). As media culture underscores the signifying value of the body, it also allows for a dual-directionality between agency and submissiveness, meaning that, as Virginia Blum notes, those who “‘submit’ to images are the selfsame subjects who create them” (50). Does this mean that Amy’s psychic pain and sense of ugliness are self-produced fictions? Not at all. It means that the delineation between consumption and production does not adhere to a simple binary—that aesthetic ideologies require subjects to both create values and feel controlled by their own creations. This, in turn, gives rise to a set of “paradoxical urges” for both freedom and domination, control and victimization, urges not unlike the pairing of anxiety and desire offered by Extreme Makeover.

The Skeleton: Extreme Makeover’s Parts and Players

[13] To understand Extreme Makeover’s deep structure, it’s helpful to get a sense of the strict formula it uses each week. Though allowing some small variation for theme shows, each episode works according to a 10-part scheme:

- Background on the participants

- “Surprise” announcement of selection

- Consultation with doctors and dentists in L.A.

- Medical work

- Recovery and (mandatory) homesickness

- Work out and styling (clothes, hair, and make-up)

- Drive to the “reveal,” where the new look is unveiled

- Reveal, universal success, and uniform elation

- Before and after pictures, post-change interviews

- “If you want to be on Extreme Makeover“

The regularity of this pattern locks participants and viewers into a common landscape, assuring a stability of both desire and potential outcomes.

[14] Other certainties also prevail on this program. For instance, all of the participants have experienced “severe” psychological pain, which they attribute to their aesthetic “disfigurement,” though none of the participants speak of abusive, addictive, or criminal backgrounds. Most of the participants are women (roughly 75%), of these a large majority are white (81% are white, 14% are black, and 5% are of Latina or Polynesian descent; of the men, 100% are white). All participants speak of heterosexual desires, though some say their “healthy” heterosexual impulses have stalled due to their appearance. All of the plastic surgeons and dentists are male, most are white (significantly, “doctors of color” operate almost exclusively on what one doctor called “the ethnic patients”). The only female physician is a dermatologist, though there appears to be a woman psychotherapist, whose work is seldom mentioned. The oldest participant is 56, the youngest 21, the average age is 32.4. Participants come from all over the United States, though there is a preponderance of small-town dwellers (from places like Lebanon, Ohio or Wilson, Arkansas) over big-city residents.

[15] The end result of the makeover typically plays out according to a Cinderella motif, with horse-drawn carriages and “enchanted” reveal parties. The look for both men and women invariably conforms to a narrow sense of celebrity-on-the-red-carpet beauty. For women, this means figure-hugging dresses, high heels, dramatic make-up, and elaborate hairstyles. For men, there is the polished GQ look, a tan, and highlights in the hair. For both, there is a mandatory “movie star” smile. This is not a show that would make over a subject so that s/he could wear Birkenstocks and overalls—or for that matter, any sort of androgynous look. Particularly for the women, the end result is high-glamour, intended to captivate the gaze. It is also, and I say this with no small irony, a look closely paralleling the drag queen in her over-determined signification of femininity.

[16] Sometimes subjects have hair lips or cleft palates, other times acne so angry that there are swollen eruptions on top of a face already multiply scarred. Sometimes subjects—in this case, entirely women—have “lost” their good looks through a life-time of being other-oriented, their pregnancies, their care of husbands and children, their work-heavy burdens having palpably written themselves on bodies that are flabby, falling, and fattened. Just as often, “worthy” subjects are those who have either been abandoned by heterosexual romance or look like they might soon be expelled from the garden of marital delights. So we see the bar waitress in Alaska whose lips are too malformed for kissing, the overweight radio d.j. whose co-worker doesn’t find him sexy, the acne-scarred dancer, too embarrassed by her appearance to date or audition. These people often get makeovers on the same show as those troubled primarily by aesthetic considerations: the woman who is mistaken for her husband’s mother, the father who is bothered because his two-year-old son laughs at his yellow and black teeth, the widow who is too dejected by her looks to re-enter the dating scene, or the nurse who is tired of “always looking average.” By pairing those with “legitimate” defects and those with “aesthetic” flaws, the show effectively collapses the difference between the two—if a cleft palate merits surgery, so does a weak chin. The subjects are not selected, then, according to their relative degree of “deformity,” since all aesthetic anxieties signal crippling disability.

[17] This crippling displeasure with one’s own looks functions as a significant criterion for participation on the show. Extreme Makeover’sexecutive producer, Lou Gorfrain, also claims the importance of the following:

- A great personality, a great story, and a not-so-great face and body;

- The “right” desire for a makeover, rather than the “wrong” one [as for instance, one motivated by revenge];

- The sort of makeover that would achieve a significant visual impact [not, for instance, surgery for varicose veins, that might be life-changing but not visually dramatic];

- A need for “not too much” plastic surgery. (“Making the Cut”)

Not expressed, but surely part of the selection process, are a wide variety of tacit criteria—no drug addictions, no sex change operations, no nefarious criminal pasts or people seeking improved images for public office. Equally, there are implied expectations: the subjects must have suffered because of their looks, they must be desperate for heterosexual romance, they must be grateful and not bitter, enthusiastic not cynical. They must come from—and go back to—a loving and supportive group of family and/or friends. (I’m still waiting for the episode when a participant gets to Hollywood and refuses to go home.)

[18] Not surprisingly, the producers want “good story,” and they are quite insistent that “good” not be synonymous with “salacious.” In fact, there is a vaguely nostalgic version of traditional moralities on this show that is perhaps refreshing in the postmodern miasma but also disconcertingly conservative. Much like Disney (ABC’s parent company), Extreme Makeover dismisses or edits out “unpleasantness,” from vanity as a primary motivation to envy among family members who vicariously experience the transformation, unless that resistance serves some sort of narrative purpose. For example, when a participant’s female boss expresses concern about the risks of surgery, she is depicted as both jealous and petty. The voiceover narrator calls her “extremely negative,” a rhetorical move that characterizes her as the Evil Stepmother to the transforming Cinderella (2-4). In the “after” segment of the show, the boss apologizes for her statements and admits she was wrong. Here again, we see a version of plurality (in this case resistance) completely excised in the name of self-improvement, which apparently requires a unification of values. Extreme Makeover is the happiest show on earth—with more tears of joy and hugs of gratitude than any program since Queen for a Day. Just like Queen for a Day, it is the suffering that makes these subjects worthy.

[19] Indeed, Extreme Makeover is complicitous in their suffering, asking participants to describe the pain they’ve experienced, inviting the viewer to gaze and gawk at the pre-surgery body dressed only in the standard-order beige bra and underwear seemingly provided to all of the Extreme Makeover subjects (men wear white briefs in their full-body before pictures). One woman noted about this form of exposure, “I don’t want my husband to see me like this, and now I’m showing all of America” (2-15). Reliving the pain inflicted on them by their bodies, complete with appropriate mood music and a spectatorial male voiceover, seems one of the mandatory links in the makeover chain. It’s a modern-day Pilgrim’s Progress where worthy subjects must undergo humiliation and endure multiple tests in order to arrive at a better place. Their suffering, coupled with their desire to be better mothers, fathers and spouses, or more committed participants in the marriage market, or more enthusiastic pursuers of their own dreams, marks them as subject material whose psychic pain can be seemingly neutralized.

[20] In a similar way, the show effaces difference in what the subjects say about their transformations at the end of each episode. To a person, each is grateful, enthusiastic, delighted. There is a sense of recommitment to one’s heteronormative engagements, a feeling of new access to meritocracy. As one participant said, “I feel as though nothing could stop me” (“Making the Cut”). There is an interesting democratization in this statement, a message of “come one, come all” that extends beyond the boundaries of the program itself. WhenExtreme Makeover participants extol “I can do anything I want to do” (2-14) or “I pretty much can conquer whatever I want” (2-5) we get the sense that all of us—with the aid of payment plans and credit cards—are eligible for empowerment through plastic surgery. And yet, onExtreme Makeover there is a homogenization in this celebration, a sense of sameness that saturates each person’s story. The overall effect leaves one thinking that individuality counts for less than regularity, a regularity brought about through the rigid formal properties built into the show itself and now crafted onto “beautiful” bodies.

[21] Pairing rigid (and primarily Western) norms of beauty with the ideals of democracy also suggests that there will be no equal treatment or opportunity until there is equal (pleasing) appearance. This notion—that one must fit within the boundaries of the “normal” before he or she can participate in democracy—creates a zero-sum game in our increasingly pluralized and globalized society. Although it’s evident that no matter how many people Extreme Makeoverchurns through the surgery machine, it can never address all of the “ugly” bodies in the world, there’s another irony here. The ideology posits normalcy as synonymous with beauty-by-the-numbers. But, since it is clearly more normal to be “plain” than to be statistically beautiful, we have to wonder just how desirable actual normalcy is. In the arena of beauty, it seems, it may not be so bad to be different from all others if that difference exists on the “extreme” end of the beauty scale where psychological pain apparently does not reside.

The Anesthetized Body: The Body and Pain

[22] Though the pain of psychological humiliation clearly figures in the construction of Extreme Makeover’snarrative, bodily pain does not. There are brief televised moments depicting surgery, and each episode contains a post-surgery shot of patients delirious or bandaged, but these images are short in duration and overwhelmed by the larger temporal field of the show. Indeed, time’s manipulation is a critical way of managing pain. In the show, we witness a collapsing of the temporal, so that an eight or ten hour surgical procedure becomes a two-minute video clip; similarly, a three-week recovery takes place in five minutes or five seconds, depending on the editing. As viewers of television texts, we are accustomed to this difference between narrative time (in this case seven to eight weeks) and textual time (44 – 48 minutes), but in the context of “reality” TV, the glosses of time smooth out pain, anxiety, social discomfort—again, the very forms of emotional distress that both signify “realness” and motivate change in the first place. So time functions in this reality show as a way of distorting realism. Time’s depiction obscures time’s arc, in the process erasing the visual evidence of physical pain even as voiceovers and personal narratives remind the viewer of emotional torment. On one show, for example, a participant, Anthony, overtaxed his body and passed out. In clips leading up to a commercial break, the viewer sees him fall several times. A “staff” doctor tells us that Anthony has “cheated” on his program by exercising too much and eating too little (a too extreme Extreme Makeover, apparently). Anthony is recovered in all of 20 seconds and soon shown headed for lasik eye surgery. In all, there is more narrative time devoted to the doctor’s reprimand of Tony than to his actual physical distress (2-16). The narrative moment, then, depicts Anthony’s desperation and the doctor’s expertise—in this case, time and pain function as tools to emphasize anxiety and authority.

[23] This is a recurrent motif. On Extreme Makeover, time and pain are ever present, yet easily managed through the powers of plastic surgery. Though participants undergo major surgery and so serious physical pain, it’s only psychological pain that counts as relevant. And even here, the promise is not that psychological pain will be eliminated, but that it will be alleviated. The show’s underlying assurance is not of timelessness or painlessness but of a better–meaning a less-troubled–experience of aging and pain. Time still passes but it signifies differently on the body. The same holds true for pain. The teasing, the sneers, the jokes may give way to psychological disorientation and potential alienation from friends, but this new pain is better than the old. As one newspaper reporter phrased it, “the risk and pain of surgery and months of healing were nothing compared to 31 years of self-loathing” (Rowling).

Dislocations: Fixing the Body

[24] One of Extreme Makeover’s more subtle promises is that it will not only alter the body’s experience of time and pain, but that it will stabilize the body, fix it in time and space, and thus make it more reliable and less potentially disruptive. Gayatri Spivak argues about body altering surgeries more broadly that such an idea underscores a “strategic essentialism” that stabilizes the performative (and threatening) possibilities of the body by fixing them surgically. Extreme Makeover largely takes up an opposite view, celebrating the idea that the good makeover is the everlasting makeover. Though there are still shelf lives on things like face lifts and Botox, it’s hard for a backslider to “undo” a nose job or a chin implant. There is a sort of stability built into this makeover that both ups the ante and seems to satisfy the objective of doing makeovers at all—the body is fixed, no longer able to be transgressive or resistant. What we see on this television program, then, are the very real ways in which the “grotesque body,” untamed by shame or surgery, represents a threat to the prevailing social order. In this configuration, ugliness becomes a social danger that validates forcible intervention. The body’s newly constructed “perfection,” in turn signifies the subject’s symbolic obedience to hegemonic order. It’s not by accident that the under girding warrants for performing cosmetic surgery on Extreme Makeover appeal collectively to traditional values: women who look and act feminine, men who look and act masculine, attractive men and women who want nothing more than to be in heterosexual and monogamous romantic union with one another.

[25] But, of course, surgically altering the body’s appearance in no way changes the body’s maddening resistance to being controlled—a point Extreme Makeover does not acknowledge. The body still erupts, resists, and operates according to a set of codes (or no codes at all) that are baffling and largely mysterious. Perfect smiles and a pleasing slope to the nose don’t prevent cancer; liposuction does not eliminate the vicissitudes of menopause. Indeed, the heartfelt hope that plastic surgery might indeed “fix” the body indicates just how powerful our collective cultural anxieties about the fluidity of the body actually are. In some ways, then, the tacit promise to perform the impossible, to solidify the liquidity of the body, reminds us of our anxieties more than it soothes them. This anxiety, in turn, serves a powerful role in legitimating and making the viewer desire beauty systems that promise a cessation of worry.

Skin Deep: A Matter of Surfaces

[26] It’s critical given this emphasis on fixing the body that the subjects on Extreme Makeover be presented as surfaces—theirs is an outside/in transformation, not an inside/out. Their interiority comes from the sadness and lack of self-esteem that result from emotional trauma. In some ways, this opens Extreme Makeover to its easiest criticism: in focusing exclusively on appearance, the show oversimplifies the subjects’ problems so that those problems can be solved with what the show has to offer—expertise in altering appearance. But this relentless emphasis on surfaces also effaces a whole spectrum of complexity. For instance, what about the actual health of these subjects? Is there a systemic imbalance in the body leading to its external “mis-shapen-ness”? Equally, is there a chemical imbalance causing the subject’s depression and/or emotional trauma? The persistent attention to surfaces prevents the possibility of both physiological and psychological interiority. Indeed, though Extreme Makeover occasionally lists a psychologist, Dr. Catherine R. Selden, in its credits, she has, thus far, only once been depicted on screen.

[27] One interesting exception to this dismissal of the psychological occurred in February 2004. In order forExtreme Makeover’s three overweight participants to be eligible for cosmetic surgery, they had to “earn” it—in this case, losing weight and inches over a three-month period. Because significant weight loss (for these subjects, between 20 and 50 pounds) requires longer than the eight weeks allocated by the program, the episodes were billed as a two-part makeover (perfect for February’s rating sweeps). For part two, enter Dr. Phil McGraw, first Oprah’s and now seemingly America’s favorite psychologist. In his down-home Texas way, Dr. Phil underscored the need to make attitude and life-style adjustments in order to assure the success of weight loss. “You have to change your thinking,” he said. “You gotta go home and clean your environment.” The subjects themselves were concerned with the very sorts of things one might imagine of a person going through significant change. Anthony, one weight-loss participant, asked, “How do I introduce myself into my life with my wife?” Dr. Phil’s response: “Deal with psychological problems psychologically” (2-16).

[28] But what exactly does that mean? Hasn’t this show relentlessly told us to deal with psychological problems cosmetically? Indeed, that our psychological problems stem from our aesthetic anxieties? If the outside depends upon the inside, but the inside exists separate from the outside, we are left with incompatible polarities. Further, in terms of actual advice, it’s not at all clear what Dr. Phil is advocating. It is clear, however, that this discourse of inside and outside works to underscore a desire for clear ontological separation between outside and inside at the same time as it collapses the difference between the two. In fact, Dr. Phil’s appearance offers less in terms of psychological interiority and more in its promise that the inside and outside function “naturally” as separate entities. “I work on the inside,Extreme Makeover works on the outside,” Dr. Phil says, as if to prove this point. Anthony reverses Dr. Phil’s model but reinforces the separation of inside/outside, when he says, “What it’s [the makeover] done from the inside is far bigger than what it’s done from the outside.” A different subject, La Paula, disallows this consequence, but again points out the ontological difference between insides and outsides, “I’m the same old La Paula. I haven’t changed on the inside” (Feb 26, 2004).

[29] In the midst of these stabilizing statements, there is a sense of slipperiness, an intimation that it’s impossible to be fully sure where either the domain of inside or outside lies. The discursive reinforcement of ontological separation heightens the sense that their confusion is frightening. Similarly, the horror that accompanies this threatened breakdown of distinctions, what Julia Kristeva has termed the abject, leads inExtreme Makeover to a full-fledged reliance on and preoccupation with images. In this case, the power of appearance functions as the “realest” state of being, thus making the image the most potent defense against boundary blurring and, in effect, heightening the authority of the show itself. Yet, as Baudrillard has theorized, in an age of simulation where images are entirely referential, “reality is dead.” What we think of as real is merely a form of “residual nostalgia,” particularly if that reality is linked to the image.

[30] It’s no wonder, given this rather bleak pronouncement on the “real,” that the popularity of makeover programs, reality television and surgical procedures should surge (and fuse) in a form of conceptual backlash. Indeed, it could well be that beauty offers the most direct link to that long-lost and idealized past where the subject was whole and the body stable. Whether nostalgic dream or attainable goal, beauty promises to arrest the deteriorating and decaying body and to eliminate the wrinkles, fat, and sagging flesh that signal the “abject.” In so doing, beauty earns the power to fix the hyperreality of the image and to restore realism. What could be more appealing?

Celestial Bodies: A Star is Born

[31] In the context of this reliance on images, it’s appropriate that celebrity functions as a critical element of the Extreme Makeovernarrative. Indeed, unlike the models of Pygmalion or My Fair Lady, where Eliza Doolittle’s transformation from a flower-monger to a “regular lady” suggests an investment in (and anxiety about) class mobility, Extreme Makeover is not interested in manners or pronunciation. Though class (as cued by grammar, teeth problems, jobs, etc.) plays tacitly at the edges of the Extreme Makeovernarrative, it’s not class itself that either must be changed or that stands as the source of all problems. The underlying crisis is one of beauty and the dire consequences that befall those who do not possess it. The motivation is not to become a lady (or gentleman) but to alter the signs of the body so that it will be read as what the culture deems most beautiful, a movie star. It’s about glamour, not grammar.

[32] Episode after episode is saturated with this fantasy of attaining movie star looks. “We gave her a beautiful, luscious natural mouth,” one doctor pronounces. “She came out looking like a movie star” (2-14). La Paula says about her teeth, “I’m looking forward to having a beautiful movie star smile” (2-16). Belen exclaims at the end of her makeover, “I felt like a movie star. I got the movie star treatment from my family” (2-16). At the close of Tammy’s reveal ceremony, her friends cry out, “She looks like Britney Spears!” (2-14). The voiceover narrator exclaims about one subject, “From suburban not to Hollywood hot” (2-13). These statements clearly suggest that surgical and stylistic procedures can catapult “normal” people into the pantheon of celebrity. Indeed, the fascination with movie star looks in itself functions as a legitimating device—see, the show seems to be saying, celebrities are the people we are most interested in and who must be happiest. Indeed, perhaps to heighten the sense that the participants are the actual celebrities of the show, Extreme Makeoverdid away with its celebrity host, Sissy Biggers, early in season one.

Figure 7

[33] As Leo Braudy has suggested, much of everyday American life reinforces that we should aspire to fame because “it is the best, perhaps the only, wayto be” (6). Looking famous implicitly means living better. Never mind that media celebrities are more firmly under the spectatorial gaze than any other figures in our culture, as photos decrying this star’s cellulited back side or that star’s scary skinniness clearly attest. The desire to be a star is the 21st-century equivalent of a fairy tale.

[34] Not surprisingly, Cinderella runs a close second in terms of makeover appeal. Female subjects constantly speak of “feeling like a princess.” Extreme Makeover often underscores this association by chauffeuring subjects to their reveal parties in horse-drawn carriages. Only a few male subjects have grasped the figurative reigns of that carriage to drive themselves—in one case John showed up at his reveal party in a Lamborghini, a move much more in keeping with James Bond than with Prince Charming (2-13). It may be one gesture toward gender inclusivity to privilege movie stars over royalty, since celebrity surely incorporates masculine fantasy and American

upward-mobility more than do fairy tales. Celebrity also functions as an implied absolution of fault and error, which, as Braudy notes, restores “integrity and wholeness” (7). The desire for autonomous subjectivity, then, is intimately tied to a desire for the celebrity’s body.

Figure 8

[35] Given this, it’s somewhat ironic that there has been an actual fame accorded to the subjects of Extreme Makeover (as compared to the more expected fame accorded to participants in other reality TV shows such as American Idol or The Bachelor). The controversy of the show’s premise as well as the ubiquity of American popular culture has fostered conversations from small-town Idaho to large cities, such as London and Sydney. The fact thatExtreme Makeover features real people undergoing dramatic (and envied) change means that local papers and television affiliates circulate the makeover stories as a way of generating home-town interest. All of this—in addition to a surfeit of reality television shows—has helped increase “reality celebrity.” Stacey Hoffman’s

Figure 9

transformation on Extreme Makeover, for instance, turned her from a thirty one year old with “mousy hair, chubby cheeks, and a hook nose,” who was overlooked by men, into a post-op reality celebrity, who is “constantly accosted and asked for autographs” (Rowling). A resident of Wahoo, Nebraska, Stacey’s story was picked up and celebrated by the Sunday Mirrorof London. Other participants onExtreme Makeoverhave been invited to tell their stories (and display their altered bodies) on shows ranging from

Figure 10

[36] “Reality celebrity” is in itself a bit of a conundrum. If it’s possible for “real” people to become celebrities, doesn’t this call into question the exclusivity implied by celebrity in the first place? Don’t we also have to ask if everyone can be physically beautiful? Since ideals are constructed around the logic of desiring what is statistically least possible, the more plastic surgery brings beauty to the masses, the less beauty signifies as privilege. As Blum puts it, “Once beauty becomes available to everyone, from all classes, races and ethnicities, then it is exploded as a site of privilege” (52). It seems, then, that the process of turning average people into celebrated beauties takes away the cachet of that beauty. As such, the very desire for movie star appearance built into the show and the consequent celebrity that befalls Extreme Makeover’s subjects work against the outcome it seeks. In order for beauty to mean anything, a good many other people in the world have to be un-beautiful. In order for celebrity to signify, the majority of people have to be unknown.

[37] Clearly, the four dozen people who have now gone through theExtreme Makeover machine are not enough to topple the vast disparity between haves and have nots, between the beautiful and the plain, between the celebrated and the anonymous. Even normalizing plastic surgery would not do this. The ideal (and rarity) of living in a beautiful body is still perfectly intact. Equally intact, however, is something that this prime time programming very much influences—the sense that we must be aware of and concerned about appearance. Whether scrutinized for our freakish ugliness or admired for our glamorous appearance, we are all objects of the gaze, intensely self conscious that there are seeing eyes (or cameras) on us at all time, even when those eyes are our own.

False Health: The Gendered Gateway to Personal Power

[38] Extreme Makeover justifies this spectatorial scrutiny not by disallowing the gaze but by claiming a “better looking” face and body enhance self-esteem, which, in turn, allows for personal empowerment. By rectifying the distance between social ideals and lived experience, Extreme Makeover proposes to make lives happier and participants more powerful. It’s an end that seems completely valid, even revolutionary in some respects. Who doesn’t deserve to be happier? Why should biology determine beauty? Why shouldn’t the vestiges of class and circumstance that write themselves on the body be not only overwritten but erased altogether? Why should the powerless always remain without power?

[39] But there is a tickling question here. How is power imagined? For power, being the nebulous thing that it is, quite often evades easy quantification. Given this, how can one truly know if s/he has more or less of it? Looking at what subjects note as profound “after” differences offers one way of understanding more fully what counts for them as power. As with Amy, a form of alteration that strikes the subjects as significant is a new feeling of wholeness. For example, Kim Rodriguez told Charles Gibson on Good Morning America, “I always believed that I was a beautiful person on the inside, and what I needed to do was have the appearance match that. So now, I just feel complete. I feel like everyone else” (“Making the Cut”). Again, we see the articulation of inside and outside positions that fuse together, overwritten by a pervading sense of normalcy. Power, in this case, comes from an experience of identity commensurate with what one assumes everyone else possesses, an idea also expressed by Extreme Makeover participant, Dana, who says, “When I look in the mirror, I see a completely different person. I’m normal” (2-4). Coupled with this sense of perceived normalcy is a belief that power comes from achieving a “truer” version of oneself, which allows for Amy’s “I’m me now” statement, or a friend to say about Benjamin, “He now looks like what he is” (2-14).

[40] Other statements suggest heterosexual attention counts as the most significant new form of power. So, for instance, a woman police detective who undergoes an extreme makeover tells Oprah that a younger man had made a pass at her. “[A] young man came up to me and he—he said . . . I had a lovely smile and would I like to go to lunch? And I’m looking at him. And it’s—you know, the first thing I’m feeling is just stunned, disbelief” (“Inside Extreme Makeovers”). Extreme Makeover recipient Tammy’s new sexual power is underscored by comments from friends who note how many men are looking at her (2-14). As if to testify to this, on a different episode a man reflects off-camera about Nellie’s makeover, “There’s a couple of guys who are wondering what’s going to happen next. I wish I never broke up with her” (2-14). A London paper writes about the after effects experienced by one Extreme Makeover participant: “Men stare, and those who once dismissed the old Stacey are suddenly apologetic . . . she has her pick of prospective boyfriends. Her current beau is Billy, a dark-haired, long-lashed fireman—but his friend Jason is also circling” (Rowling). Though not always with such potent shark imagery, these are repeated and insistent refrains—the pay-off to changing yourself is possessing a coherent identity and attracting an appreciative gaze (particularly for women).

[41] Through a sort of trickle-down theory of empowerment, these two dividends of the makeover also yield greater competence and agency in the world, localized primarily at the site of gender. Accordingly, being looked at in an appreciative or sexualized way affirms a woman and, in turn, allows her to be a more confident (and more traditionally feminine) wife or mother. In her increased confidence, she is able to assert herself more, get more done, stop hiding herself, and, rather tautologically, attract more positive and sexualized attention. Extreme Makeover announces that it might not only be easier but more politically advantageous to “join” them rather than “beat” them, to be looked at appreciatively rather than critically.

[42] Such a construct implies a rather paradoxical notion that being the object of the gaze can allow one power over the gazing. This idea subverts classic gaze theory because it suggests that objectification yields agency and, thus, subject status. The sort of gazing done onExtreme Makeover, as a result, is both resolutely conservative and potentially disruptive. Extreme Makeover uses the gaze to discipline the gazer, a rather classical configuration that posits looking as male, meaning that the women on the program (and the viewers at home) enact a masculinized gaze. But the program also allows for multiple viewing positions and highly complicated notions of looker and looked-at, thus opening up new spaces for spectatorial surveillance and pleasure. (For more extensive conversations on gaze theory and scopophilia, see Mulvey, Doane, Studlar).

[43] But even given the complicated gazing on this show, notice how a woman achieves subjectivity—by increasing her claim to a popularized magazine-issue form of beauty. In this case, beauty functions as a form of necessary female currency. Through a system of equivalencies, beauty enables the woman to “purchase” other valued objectives—good mothering, sexual attention, an abstract kind of happiness, and even her womanhood. As one makeover recipient told Oprah, “I feel like a woman. I feel feminine. It’s nice” (“Inside Extreme Makeovers”). Expanding what makes the woman beautiful, then, ostensibly expands her base of power. But again, we see that the terms for that power have not altered. A woman’s power is here constructed through a very narrow sense of beauty that is unwrinkled, symmetrical and eternally youthful. The post-menopausal “old crone” is pushed even further into the abject, becoming not just powerless but horrifying.

[44] While it makes perfect sense from the point of view of patriarchal values, then, that female power would be constructed in terms of beauty, how does it work for men? Does the fact that men feel anxieties about their appearance announce the possibility of difference? Perhaps. It is true that both Extreme Makeoverand media culture at large put men under a spectatorial gaze, a logic that presumes their objectification. But we must be careful about assuming a true parity. Though there are ways in which men are feminized by fat and anxieties about appearance, particularly onExtreme Makeover, passive and feminized images of men can sometimes underscore patriarchal values rather than recast them. Along this line, Abigail Solomon-Godeau argues that narratives depicting the idealized male body serve to instantiate a fascination in maleness and masculinity. Rather than upsetting the structures of the patriarchy by destabilizing the gaze, she suggests, looking at the male body allows for a “cultural fantasy in which the feminine can be conjured away altogether” (73). It may be, then, that by including male bodies in the makeover machine, we see an underscoring of patriarchal systems that can be damaging to both men and women.

[45] Yet, even taking into consideration how Extreme Makeovermanipulates gendered desires in order to promise improved personal power, it’s impossible to dismiss the real consequences of aesthetic alteration, for both men and women, nor do I particularly want to. It’s evident that one holds more authority within hegemony when one concurs with it. Good looks, and here I’m defining “good” as those in alignment with pervading beauty ideals, undoubtedly lessen social criticism. Indeed, if we are willing to grant a fat/ugliness oppression, doesn’t it make sense to imagine a thin/beauty empowerment? Feminist critics, myself included, would be quick to point out the logical fallacy here. This sort of binaried pairing—fat, ugly and resistant on one side and thin, beautiful and obedient on the other—necessarily organizes our thoughts in terms of conceptual opposites. If we move away from one position on the binary—the ostracized outsider who feels victimized by social censure—the only position allowed for is the perceived opposite—the beautiful insider who feels empowered by social approval. Both of these binaried positions are pre-established by a patriarchal logic; both positions underscore sameness, neither possesses defining power. The privilege conferred by aligning oneself with hegemonic values, then, is contingent on and subordinate to the power granting authority. So Amy and Tammy and Nellie and John may gain more agency and confidence, but not enough to remove themselves from the social network entirely as Amy speculates. Indeed, it’s doubtful Amy would exempt herself from the social system even if she could, since her new-found currency is intimately tied to the overarching values of that system.

[46] We begin to see, then, that the empowerment one might achieve through a radical makeover is complicated and problematic. Though Sander Gilman argues, “the belief we can change our appearance is liberating,” I’m more inclined to think that changing our appearance makes us believe we’ve been liberated (3). I wouldn’t go so far as to say this is a matter of false consciousness, however. There is certainly more cultural cachet in being perceived as beautiful, more privilege in upholding hegemony than in resisting it. The participants in this show seem sincerely joyful, and it is true that changing the body alleviates psychic anxieties. Further, if my viewing practices are in any way indicative of the larger cultural audience, there is something deeply recognizable about the pain and relief each participant expresses, for I am touched each week by the profoundly different sense of body and self brought about during the extreme makeovers.

[47] I believe the problem rests in thinking in power terms at all. Interrogating makeovers at the site of power is one way to continually underscore hegemonic values because the analysis necessarily ratifies the language of those values. It strikes me as less conclusive to search out the ending of what the post-makeover body brings than to examine the competing and contradictory logics at play in bringing this body into being. My argument more broadly suggests that identifying modalities of power may be a conceptual red herring that distracts us from examining the ways in which our embodiment offers critical information about the particularities of desire and anxiety.

A Method in the (Makeover) Madness

[48] By tapping into the zeitgeist of anxieties about the body out of control and the contradictory desire to be both “famous” and “normal,” ABC has created a text rich in theoretical complexity. In its narrative of psychic pain, physical transformation and happily-ever-after endings, Extreme Makeover offers a variation and repetition on a favorite story that’s one-part fairy tale and one-part American dream. Instead of Cinderella wishing for her Prince Charming and having a fairy godmother come to the rescue, we see an “average” person wishing for the beautiful/celebrity body aided in the process by a well-meaning plastic surgeon. Instead of the exiled immigrant coming to America to partake in the great promise of democracy, we see ostracized ugliness brought into meritocracy through glamour. Unchanged between fairy tale, myth, and prime time is the degree to which narrative functions as a controlling device to monitor our desires through fantasies of self-improvement and cautionary tales that evoke anxiety. Also unchanged is the way in which wish-granting narratives are critically about the business of shaping what we should desire in the first place.

[49] Beauty, we are told, is the salve for all wounds, and beauty promises the ultimate reward—attention. This world where “everyone must look at [me] and nothing else” seems to signify the culmination of fantasy, the ultimate monomaniacal form of power where the body is fully validated by the fascination it commands (Miller). Indeed, we can see this promise uttered through the system of equivalencies Extreme Makeoverposes: beauty is health, beauty is confidence, beauty is happiness, beauty is romantic love, beauty is stability, beauty is prosperity, beauty is democracy. In the way of the most powerful and cunning of cultural texts, Extreme Makeover offers what cultural narratives have long made us believe in and desire—coherence, acceptance, self-improvement, and equality. All of this, it suggests, can be purchased through the currency of beauty.

[50] Though the end result seems to bring participants some measure of these rewards, there is an insistent reminder that the very achievement of the ideal diminishes its cachet. Consequently, whileExtreme Makeover seems to announce democratic free access, it also privileges exclusivity since beauty stands as the gatekeeper to the domain of our desires. Given its symbolic weight, it’s no wonder that our sense of appearance can so rattle our individual and collective psyches. Indeed, I would argue that this psychological un-ease might be the largest defining goal of not only Extreme Makeover but of the television makeover genre more broadly. For in the land of makeover shows, whether “before” or “after,” one refrain rises above all others—self-improvement (understood almost ubiquitously as attaining a narrow form of physical beauty) requires a speedball mixture of desire and anxiety.

[51] Some might argue that who authorizes and performs change is less significant than the fact that change happens at all. Perhaps by celebrating plasticity through its narrative of transformation, Extreme Makeover signals the disappearance of a unitary subject and the appearance of a radical new subjectivity that is fragmented, fluid, and flexible. If so, couldn’t this shift be a cause for celebration in the way it breaks down boundaries, denying phallogocentric dualisms and allowing for a sort of difference and gender performativity? At some levels, I’d argue yes, though theories of difference and performativity require plasticity, a malleability that highlights multiple change. OnExtreme Makeover corporeal transformation is not one of several options that can be taken up and experimented with at will—as a form of drag or performance. Instead, changing the body functions as a complete and coherent identity in itself that radically (and permanently) overwrites the fractured and ugly body.

[52] So, though Extreme Makeover offers a sort of difference, it does not endorse difference. Instead, it endorses a form of change that will allow the subject to embody social expectations. Ostensibly, these expectations relate only to beauty, but beauty here functions in indexical relationship to other social norms, from gendered behavior to discourses of authority. In all, Extreme Makeover reifies sameness. This economy of sameness, which comes under the banner of new-found personal power, shuts down possibilities for subversive forms of play and performativity.

[53] Cultural anthropologists have argued that anxieties about policing bodily excesses are most prevalent in cultures where external boundaries are under attack (see in particular Mary Douglas’s Natural Symbolsand Purity and Danger). We can see this, quite specifically, in recent U.S. anxieties over terrorism, punctuated by the attacks on September 11, 2001. Extreme Makeover debuted in December 2002, and in many ways our collective emotional investment in the show could be read as a larger hope of enforcing boundaries, in effect regulating the social body’s pluralism by imposing uniformity on the individual body. Ultimately, however, I would argue that the contentious state of the world is less at issue for Extreme Makeoverthan is a deeper investment in our collective desire and anxiety. In many ways, this form of boundary policing is not about a culture under siege but a culture believing itself under siege. The belief that we are threatened legitimates fear. Fear and panic, in turn, authorize anxiety. Anxiety, in turn, underscores desires for wholeness/perfection/beauty. Beauty, in turn, is elusive. When this elusive beauty becomes the only talisman to ward away anxiety, it’s evident that anxiety increases. The dialectic is endless—one seeking out the other, the other always deferred. By keeping us firmly transfixed in the cycling of anxiety and desire, a cultural text likeExtreme Makeover perpetuates the puzzling logic that authorizes its very existence, making it impossible for us to seek out, much less imagine other possibilities for life, for love, for “wholeness.” This economy of sameness is, perhaps, the most extreme, and the most dangerous, consequence of Extreme Makeover.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the colleagues, friends and students who helped in the development of this essay, particularly by sharing their own stories about body image and its attendant anxieties. Special thanks to the anonymous reviewers, Ann Kibbey, Karen Tice, and, as always, Greg Waller, for careful readings and helpful suggestions.

Works Cited

- Bakhtin, M. M. Rabelais and His World. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1984.

- Baudrillard, Jean. Simulations, Semiotext(e). New York: Columbia University Press, 1983.

- Blum, Virginia. Flesh Wounds: The Culture of Cosmetic Surgery. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

- Bordo, Susan. Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

- Braudy, Leo. The Frenzy of Renown: Fame and Its History. New York: Oxford UP, 1986.

- Butler, Judith. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex.” New York: Routledge, 1993.

- Davis, Kathy. Reshaping the Female Body: The Dilemma of Cosmetic Surgery. New York: Routledge, 1995.

- Doane, Mary Ann. Femmes Fatales: Feminism, Film Theory, Psychoanalysis. New York: Routledge, 1991.

- Douglas, Mary. Natural Symbols. New York: Pantheon, 1982.

- ——. Purity and Danger. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1966.

- Dutton, Kenneth. The Perfectible Body: The Western Ideal of Male Physical Development. New York: Continuum, 1995.

- “Dying to Look Good.” People. March 22, 2004. 89-90.

- “Making the Cut: Extreme Makeover Kim Rodriquez Receives a Makeover.” Good Morning America. ABC. January 23, 2004.

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

- Gaines, Jane, ed. Fabrications: Costume and the Female Body. New York: Routledge, 1990.

- Gilman, Sander. Making the Body Beautiful: A Cultural History of Aesthetic Surgery. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1999.

- Haiken, Elizabeth. Venus Envy: A History of Cosmetic Surgery. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1997.

- “Hollywood Confidential.” People. March 15, 2004. 67-76.

- Home, Sue and Deborah Jermyn, eds. Understanding Reality Television. New York: Routledge, 2004.

- “Inside Extreme Makeovers.” The Oprah Winfrey Show. January 9, 2004 (repeated from November 2003). Harpo, Inc.

- Klein, Sarah A. “Trading Faces: Reality TV Fans Flock to Plastic Surgeons, Seeking the ‘Extreme Makeover’ Treatment.” Crain’s Chicago Business. March 9, 2004.http://www.crainsdetroit.com/cgibin/news.pl?newsId=3778

- Merish, Lori. Sentimental Materialism: Gender, Commodity Culture, and Nineteenth-Century American Literature. Durham, NC: Duke, 2000.

- Miller, Mark Crispin. Plenary address to the Society for Cinema and Media Studies. Atlanta, GA. March 2004.

- Murray, Susan and Laurie Ouellette, eds. Reality TV: Remaking Television Culture. New York: NYU Press, 2004.

- Mulvey, Laura. “Afterthoughts on ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ inspired by Duel in the Sun.”Framework 15/16/17, 1981.

- —–. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen. 16:3, Autumn 1975: 11-12.

- Radner, Hilary. Shopping Around: Feminine Culture and the Pursuit of Pleasure. New York: Routledge, 1995.

- Rowling, Denise. “An Extreme Makeover Changed My Life: An American TV Show is Giving Women the Chance to Transform Their Lives.” Sunday Mirror. January 18, 2004.

- Saturday Night Live. National Broadcasting Company. May 8, 2004.

- Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. Male Trouble: A Crisis in Representation. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- Studlar. Gaylyn. In the Realm of Pleasure: Von Sternberg, Dietrich, and the Masochistic Aesthetic. Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 1988.

- “Real Life Extreme Makeovers.” People. Nov 17, 2003: 74-80.