Race, Gender and Terror: The Primitive in 1950s Horror Films

(part of a series in Special Issue #40: Scared of the Dark: Race, Gender and the “Horror Film” – Guest Editor: Frances Gateward)

[2] Neil’s transformation is not just from white to black but from modern to primitive. At first, Neil believes that he has Chippewa blood in his ancestry, but he is not as disturbed by his supposed “Indian” heritage as he is by the subsequent revelation of his African-American blood. His move into blackness is figured as a slide down both the social scale and the chain of being, from the status of the quasi-acceptable Chippewa to the more stigmatized African-American. The genealogical becomes the evolutionary; Neil’s passing impacts not just his family tree but his very species. Fairly early in this process of Darwinian abjection, his wife Vestal receives a hateful letter from an anonymous source, sarcastically praising her for her “loyalty in sticking to a member of that Neanderthal tribe”(226).[1] In Sinclair Lewis’s satirical novel Kingsblood Royal, published in 1947, Neil Kingsblood—a prototypical white suburban man—begins a quaint genealogical search on the behest of his slightly eccentric father who believes that the family lineage may stretch back to European royalty. What Neil finds out, in the course of his research, is that one of his ancestors, his great-great-great-grandfather Xavier Pic, was a ” full blooded negro” (59), thus making him an African American by virtue of the ” one drop rule.” Quite suddenly, Neil finds that he is black, despite all of the visual and social indicators. As he slowly but inexorably and compulsively announces his blackness, he and his family are subjected to rising levels of prejudice, culminating in a near lynching.

[3] Neil’s devolution into primitive blackness carries with it a sexual component. The letter to Vestal continues: “Gracious, what a good time he must give you when you cuddle and scream!!”(226). Vestal is, as her name suggests, the white virginal woman at the mercy of the primal sexual allure of the black man and of her own conflicted desire. Earlier in the novel, a group of white party-goers list what they know about African-Americans: “All Negro males have such wondrous sexual powers that they unholily fascinate all white women and all Negro males are such uncouth monsters that no white woman whatsoever could possible be attracted to one”(180).

[4] These racist jibes are by no means accidental; Kingsblood Royal is pointing to important aspects of racial discourse in the post-World War II era, particularly the intense anxieties concerning passing, desegregation, interracial sex, and the difference (or lack there of) between the primitive and the civilized. It should be no surprise that these fears find expression in horror films, arguably the most popular genre of the 1950s. Horror movies during this period, especially those with elements of science fiction, feature a plethora of racially coded “uncouth monsters,” bestial creatures that crawl up the evolutionary ladder. A short list of films featuring devolved monsters would include Bride of the Gorilla (1951), The Neanderthal Man (1953),Monster on the Campus (1958), The Creature from the Black Lagoon(1954), The Revenge of the Creature (1955), The Creature Walks Among Us (1956) and King Kong (1933), which was “repeatedly revived in theatrical, television, and drive-in showings” during this period (Erb 123). In addition, Bigfoot and the Yeti are featured in a number of films, such as The Snow Creature (1954), Man Beast(1956), The Abominable Snowman (1957) and Half Human (1957).

[5] While the primitive has been a staple of cinema since the silent era—the spear-carrying moon-men ofTrip to the Moon (1902), for example—the intensification of the popularity of these creatures during the 1950s signals a deep fear concerning the evolutionary potential of humankind and the tenuous status of civilization, due in part to the cultural effect of the atomic bomb and the threat of nuclear war. In her bookParanoia, the Bomb and 1950s Science Fiction Films, Cyndy Hendershot describes the violent, divisive force of nuclear weapons on conceptions of human potential and progress: “Atomic energy was portrayed as the force that could lead postwar society to a utopian existence; the atomic bomb threatened to plunge the world into a horrific dystopia” (75). As Hendershot argues, these two possible outcomes are intertwined in the paranoid logic of the 1950s. The future is really the past; the stated fear of many commentators was that the promise of atomic power could bring the devastation of nuclear war, sending us back to a new Stone Age, a fate played out literally in Teenage Caveman (1958).

[6] It is difficult to overestimate the effect of the atomic bomb on the American cultural consciousness, but there are other important contexts within which these films and their attendant fears may be understood. In Kingsblood Royal, the white suburbanites end their proclamation concerning the dangers of black sexuality and the contradictory nature of white female desire with a simple, but revealing, statement: “This is called Biology” (180). For the sake of this paper, I would like to take this last sentence as accurate in that it reveals the potentially racist and deeply conflicted nature of scientific discourse during the 1950s. My purpose in this essay is to place key filmic examples—the three movies featuring the Creature, particularlyThe Creature Walks Among Us, and Monster on the Campus—within the context of the popular discourse concerning evolutionary and genetic science in order to examine the construction and erasure of racial difference, as well as the critical role that gender plays in this ideological calculus. I hope to prove that in these films, in differing ways, the typical passing narrative becomes inverted and internalized within the white male body, thus complicating notions of racial purity, the basis of patriarchal white supremacy.

Missing the Link: Evolution as Passing Narrative

[7] The first two films in the Creature series—The Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Revenge of the Creature—begin with an expedition into the Black Lagoon, located deep within the Amazon, a primitive space marked as exotic, beautiful and dangerous. The heroes consist of a group of white scientists (with the notable exception of Dr. Maia) as well as various crewmembers. In the first movie, the majority of the crew of the expedition is made memorable by their over-determined ethnicity (they wear primitive, "native" clothing or speak in heavy accents) and their expendability (they are usually the first to die by the Creature’s hands). Only Lucas, the boat captain, possesses a sense of agency. As representatives of white civilization, the scientists/heroes of The Creature From the Black Lagoon encounter, battle and eventually kill the racially coded prehistoric monster. In The Revenge of the Creature, the Creature—still alive—is taken from his natural habitat, placed in a “Sea World” style amusement park, and subjected to torturous scientific experiments; eventually and inevitably, he breaks out and wreaks havoc. Taken together, the narrative of the two films resembles King Kong; an expedition encounters a primitive, dangerous monster who is taken back to civilization, only to escape, terrorize the local populace, and be killed through the use of modern weapons.

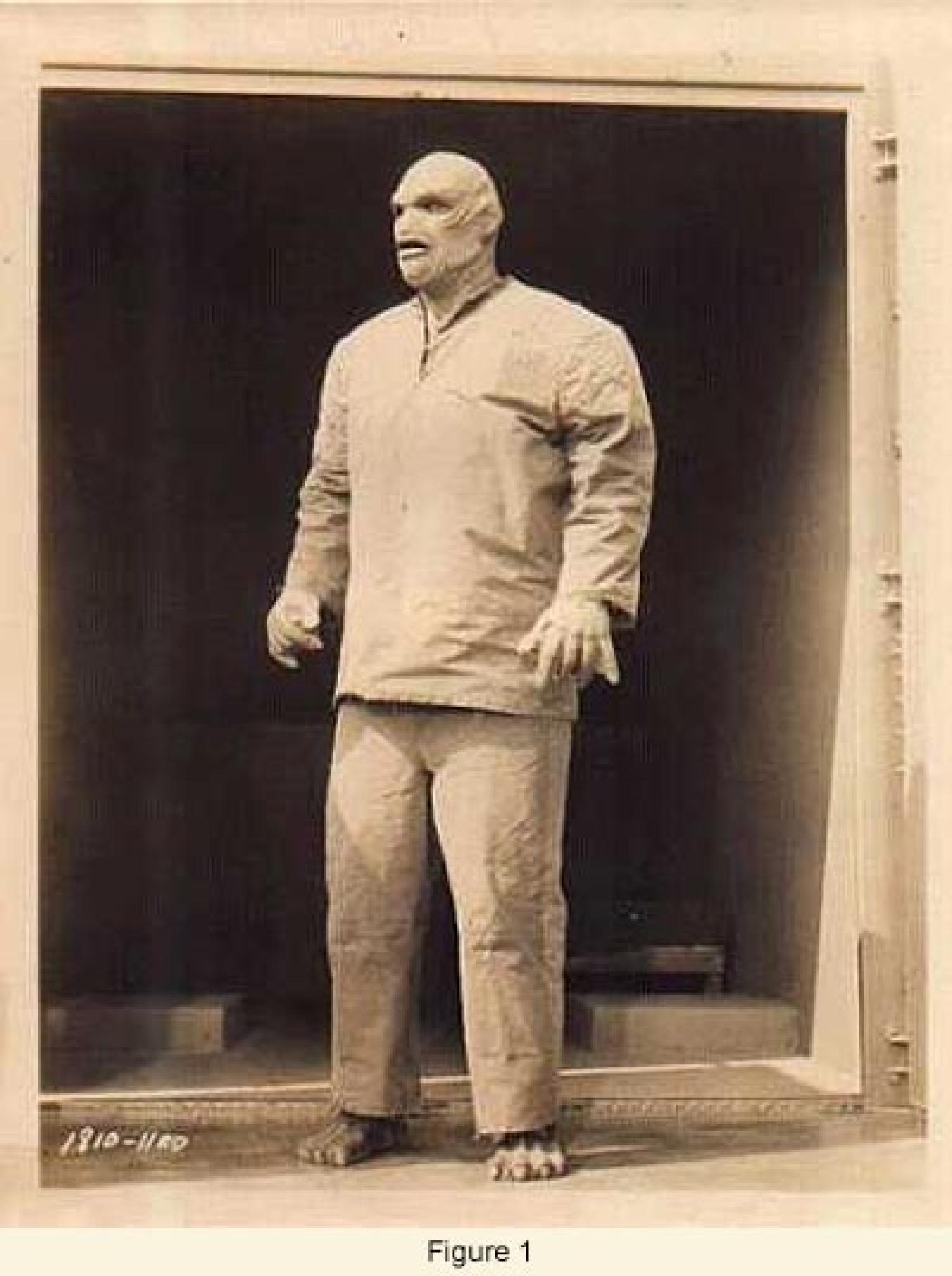

[8] In this sense, these first two movies featuring the Creature are ethnographic films, as described by Fatimah Rony. Like Kong, the Creature is an “ethnographiable monster” (Rony 15) whose primary purpose is to concretize racial difference, as “living evidence of a biological progression” (Rony 194). As this primitive monster, the Creature is an evolutionary aberration, fixed in the moment when life from the sea stepped onto the land. As a half human/half fish hybrid—he is often referred to as the Gill-Man—the Creature is a symbol of miscegenation, a tragic mulatto who does not fit into either world; his oversize lips are meant to be fish-like, but they also match the racist stereotype of African-American physiognomy.

Figure 1

[9] In this ethnographic narrative, white men have evolved and other races have not; non-whites are fixed while white men possess a kind of mobility. The anthropologists featured in Early Man, a Time-Life book published in 1965, journey into Africa in order to study the “The Timeless People” (Howell 177), natives supposedly frozen in the evolutionary process. Many horror films replicate this colonial plot and present white characters—often scientists—who are able to traverse up and down the evolutionary ladder at will and remain unchanged, like the various expeditions in The Lost World, King Kong, and the Creature films. In all of these cases, the non-white monsters are not trapped in the primitive space and time as much as they are essential to it. When they are brought back to modern white civilization—and they invariably are—disaster occurs, as seen most movingly and spectacularly in the tragedy of Kong. The “timeless” quality of this monster seems to demand that it be brought into violent contact with modernity; it is necessary to force the primitive to leave Skull Island or the Black Lagoon in order to clarify its fixity within that primeval space. By treating the “indigenous body as the site of a collision between past and present” (Rony 15), these films establish and police an unequal conduit of contact between the civilized and the primitive.

[10] This difference in power is as much epistemological as it is temporal or geographical. If—following white supremacist ideology—the only truly evolved man is a white man, than only white men truly understand their place in the evolutionary scheme of things. Many textbooks written in the 1950s emphasize that man is the “first and only creature to be aware of his own evolving”(Moore 170), a point emphasized emphatically by Prof. Blake in Monster on Campus. This awareness places them in a meta-temporal, spectorial position; they can stroll like the “flâneur at the fair” (Rony 42) and witness the spectacle of the ethnographic monster, utilizing a kind of Darwinian white gaze.

[11] During the 1950s, this mobility was in danger of becoming unidirectional. Many scientists and eugenicists of the time feared that civilization acted as a hindrance to human development. Modern society protected “weaker” individuals from the savage test of the survival of the fittest and thus held back or even reversed the evolutionary flow towards “perfection.” In Evolution, a Time-Lifeedition published in 1962, the authors describe “inconclusive studies” which show that those “scoring low on intelligence tests tend to produce more children than those making high scores.” While criticizing these reports, the authors condone the basic fear expressed within them:

Even setting aside the so-far unsubstantiated fear that humanity is now genetically discriminating against its own intelligence, some leading men in the field are apprehensive about the direction in which modern scientific and social advances are carrying man and his gene pool. [Nobel Prize winning geneticist Hermann] Muller has called the present trends “a kind of natural selection in reverse.” (171)

The speculative threat to “man and his gene pool” is the dangerous, regressive nature of modern, white civilization, which has progressed to the point that its own achievements have derailed the proper evolutionary path.

[12] The link between race and these fears concerning devolution can only be understood by taking into account the effect of the Civil Rights movement in the postwar era. Social equality implies access to the privileges of white society, often through the edict of law. Many pro-segregationists, including scientists, echoed arguments made during Reconstruction; they maintained that such legal means were against the “natural” order of things, that if blacks were meant to be equal, they would become so over time. In this racist framework, efforts toward social equality impair the evolutionary process of the survival of the fittest, a process in which surely the white male is seen as the most likely candidate to survive. In Genetics and Man, published in 1953 and revised in 1964, C. D. Darlington argues for “racial tolerance,” but this “happy aim…cannot be assisted in the long run by make-believe, certainly not by a make-believe of equality in the physical, intellectual and cultural capacities of such groups” (259). He goes on to state:

Individuals and groups which are genetically similar are bound to compete with one another. Only when they are genetically different can help predominate. Whether they do help one another, of course, depends of heredity and education, but the education can be of no use if it does not depend on a recognition of the laws of nature. (259)

Darlington posits that social equality can only exist if genetic differences between races are acknowledged, but these genetic differences, as he argues in the previous sentence, support a supposedly natural racial hierarchy. Only by being unequal will blacks be equal. In this white supremacist twist of logic, social equality, especially with its implication of potential interracial mixing, is a force toward evolutionary regression.

[13] The difference then between the civilized and the primitive is also the color line; to be civilized is to be white and to be primitive is to be black. After Brown vs. the Board of Education, this threat to the color line—the basis of white supremacy—is no longer speculative. For those that opposed desegregation, the Brown decision would lead to interracial mixing, to the dilution of white purity. More so, the decision undermined the concept of race itself by highlighting the importance of environmental factors in the development and success of an individual and further undercutting a deterministic and ultimately fanciful theory of genetic racial difference.

[14] The place of women, particularly white women, within this conflict becomes especially vexed. In the 19th century, scientists such as Paul Broca argued that white women and blacks were below white men in the evolutionary chain of being. To Broca, “’Inferior’ groups are interchangeable in the general theory of biological determinism” (Gould Mismeasure 135). Like the racial primitive fixed in time, white women were seen as basically “generic” and “sexually passive”; the white man alone “had the evolutionary function of variability” (Bederman 107). Rony contends that the portrayal of figures such as Ann Darrow in King Kong“reveals a cinematic fascination with beautiful white women as unconscious source of disorder.” The white woman is the “pillar of the white family, superior to the non-white indigenous peoples, but also as a possibly Savage creature, inferior to the white men”(174). In the 1950s, as Hendershot argues, female monsters such as the queen ant in Them! (1954) “represent the feminine degenerative Other that lurks behind masculine civilization.” Rational masculinity had to guard itself from the forces of “female irrationality” that threatened to drag civilization back toward the primitive (85).

[15] This connection between white femininity and black masculinity had to be managed very carefully since it poses a real threat to white patriarchy. As Linda Williams states, “Citizenship had transformed the black man from a piece of property into the potential owner of property, including the property of women”(104). The possession of the white woman, her place within the racial hierarchy, becomes increasingly contested and crucial to the maintenance of white supremacy. At the same time, shifts in the gender makeup of the work force signaled the increasing, although highly contested, power of white women, and the growing difficulty in determining their “ownership” as necessary symbols of white racial purity.

[16] Within this circuit of racial and sexual difference, the white woman represents the possibilities within evolution, of both forward and backward movement; she marks the space between the civilized and the primitive, a position of intense and anxious visibility, as contrasted to the relative marginalization or invisibility of the woman of color. In the Creature series, as many critics have mentioned, there exists a powerful sympathy between the monster and the female leads. At the same time, the basic narrative of the Creature series, especially in the first two films, is fueled by the violence of the Gill-Man’s attraction to and pursuit of the female lead and the white male hero’s need to protect her from the monster, a narrative with obvious racist dimensions. The Creature is the primitive black man threatening the white woman, the whiteness of these female characters emphasized by the absence of women of color as even minor characters in the three films.

Figure 2

[17] Robyn Wiegman describes how the threat of the “phallic black beast”(98), the imagined African-American rapist, validated the actions of lynch mobs. Wiegman cites Senator Bill Tillman’s address to Congress in 1907, in which he argues that the black rapist has “put himself outside of the pale of law, human and divine…Civilization peels us off…and we revert to the …impulses…to “kill! kill! kill!”(96). In Wiegman’s analysis of Tillman’s virulent and hysterical racism, the “racialized opposition between civilization and primitivity” collapses “in the face of the black brute, as the white man loses his civilized veneer. Like skin, civilization ‘peels us off’ and only an aggressive impulse remains” (97). The white woman is the “keeper of the purity of the race” and via this symbol, white men “cast themselves as protectors of civilization” even as they resort to savagery (97).

[18] This economy of lynching is the means by which difference—both racial and sexual—is visualized and narrativized. The Creature is akin to the bestial Gus from Birth of a Nation (1915), the primitive black rapist who threatens white femininity and whose actions validate white male aggression against those of color. Although the Gill-Man is a much more sympathetic figure than the highly demonized Gus, he shares his fate in the first two films of the Creature series. Both The Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Revenge of the Creatureend with the monster presumably dead, having been killed by white men galvanized into action by the abduction of the various female leads. The Revenge of the Creature is particularly illustrative, concluding with groups of white men in jeeps scouring the southern landscape of Florida for the Creature and his intended victim.

[19] In the 1950s, the importance of this racist evolutionary narrative takes on even greater importance due to desegregation. Rony, citing the work of Johannes Fabian, states that “anthropology is premised on notions of time which deny the contemporaneity—what he calls coevalness—of the anthropologist and the people he or she studies”(10). The dissemination of evolutionary theory within popular discourse, with its inherent racist bias, reconfigures the racial hierarchy of white supremacy in a temporal schema. Blacks may exist in close spatial proximity to whites; they may ride on the same bus, they may be in the same theater, but they are separated from whites by centuries of time. This racist interpretation of Darwin’s theories racializes time itself in order to ensure that segregation remains in place.

[20] The use of evolution to support white supremacy works in opposition to more radical elements in Darwin’s theory that seriously undermine ideas concerning white racial purity. Before Darwin, in the 18thand 19th centuries, the primary theories concerning human origins were divided into two camps, both of which posited white superiority. Monogenism asserted a single, perfect and white source for civilization; racial differences were determined by the amount of “degeneration from Eden’s perfection,” each race having “declined in different degrees, whites least and blacks most” (Gould Mismeasure71). The competing theory, polygenism, was even more openly racist; whites and black shared different ancestors and were radically different species.

[21] In his lecture, “Evolution and Human Equality,” Stephen Jay Gould describes how evolutionary theory should have wiped out the racism inherent in monogenism and polygenism, forever altering the family tree in which whites are superior to other races. According to most versions of evolutionary theory, all humans developed from the same source; the differences between races are either superficial or overshadowed by more fundamental commonalities. Evolutionary theory, as it was formulated in the 1950s and early 1960s, posited the existence of a common black ancestor and Africa as the “cradle of civilization,” although with some reservations. This reticence is clear in a sentence from the textbook Evolution, published in 1962: “A million years ago, some of those near-men of South Africa—who may or may not have been among our direct ancestors—took to globe-trotting” (Moore 165). Despite this qualification concerning the “near-men,” popular evolutionary theory did posit a point of origin in Africa, an assertion made even more prominent in the public discourse of the late 1950s by the discoveries of the Leakey family. In essence, the work of paleontologists sets up a genealogical timeline on which, following a strict application of the “one drop rule,” we are all are black, whether we are 1/32 black (as in the case of Neil Kingsblood) or 1/1,000,000.

[22] Of course, the debate concerning the geographic origins of early humans is lively and on going. My purpose in this essay is not to enter into this discussion but to point out how, despite the best intentions of well-meaning scientists, this debate carries a racial dimension. In Race and Human Evolution, Milford Wolpoff and Rachel Caspari recount how they were contacted by a racist individual who had mistaken their theory of multi-regional human development as a return to polygeny, as proving that white and other races have different origins (54-55). To put it simply, while it is has been contested, the assertion of Africa as the common alpha point of humanity challenges white supremacy.

[23] As Gould argues, Darwin’s theories were also quickly appropriated in order to bolster white supremacist claims; the vast gulf of time separating the primitive and the civilized was used as evidence of the radical difference between racial origins and modern, white civilization. The link between a black, primordial ancestor and a white, fully evolved man is stretched until it becomes meaningless. Even if whites came from the same source as blacks, it was argued that they had evolved far beyond this primitive past, unlike other, less civilized races. The radical implication of evolutionary theory—that blackness is at the heart of white civilization—is repressed through a revised, secular monogenism

[24] Thus, evolution was used to justify, with supposed scientific evidence, white supremacy. Darwin himself regarded slavery as a “great crime”(121), and while he still positioned “less civilized” races as being closer to animals than the Western, white male, his theories complicate any easy vision of white supremacy. Darwin states, “Differences of this kind between the highest men of the highest races and the lowest savages, are connected by the finest gradations. Therefore it is possible that they might pass and be developed into each other” (67). Obviously for Darwin, the “highest races” are really one race—the Anglo-Saxons—as evidenced by his examples of Howard, Clarkson, Newton and Shakespeare as exemplars. Yet, he also acknowledges that the “lower” races can “pass,” and white and black may develop “into each other,” a subversive possibility in which the teleology of evolution is revealed to be a passing narrative.

Walking Among Us: The Creature Crosses the Color Line

[25] The Creature Walks Among Us, directed by John Sherwood, is certainly the most critically maligned of the Creature series. However, in this final film of the trilogy, conflicts concerning race and gender brewing in the first two installments are made explicit in ways that are both problematic and promising. The Creature From the Black Lagoon begins with a lesson on evolution, emphasizing the moment of amphibious transition between sea and land. In The Creature Walks Among Us, the Gill-Man has evolved; after being captured by a group of scientists, he sheds his gills and becomes an air-breather. The Creature then moves out of the liminal space between the primitive and the modern, entering into white civilization as a symbol of evolutionary mobility and racial flux. This new status is symbolized by a shift in the primitive space as well. In contrast with the other two movies, this film begins with a scientific expedition not to the Amazon but to the Florida Everglades where the Creature is hiding, still alive after his supposed death at the conclusion of the second film. The Black Lagoon is no longer a remote, exotic space but is now replicated within the United States.

[26] The Creature’s transition from the water to the land taps into racist fears of desegregation—the Creature now “walks among us”—as well as the potential fears of non-whites concerning the loss of identity through assimilation with white culture. The Creature is not fully human/white but is prohibited from returning to his previous amphibious position in which he was (relatively) free from and in opposition to the white scientists who now control him. He is a racially hybrid monster who demonstrates Darwin’s promise concerning the ability of “lower” races to move up the evolutionary ladder, although ultimately, he challenges the very existence of this racial hierarchy.

[27] Dr. Barton, the egomaniacal leader of the expedition, wants to capture the Creature in order to experiment on it. He maintains that if he can change the blood of the monster, the “gene structure will be affected.” His goal is to then use this knowledge to help mankind evolve, in order to take the “next giant step into outer space.” The idea that studying the Creature will help in space exploration is a holdover from the first film; David, the male hero of The Creature from the Black Lagoon, asserts that learning how the Gill-Man evolved will teach us how to survive in hostile, alien environments. This rationale has mutated by the third film in that “outer space” becomes a symbol for the superiority of whiteness, rather than the need for white men to adapt and change. Throughout The Creature Walks Among Us, characters—particularly Dr. Morgan, played by the perfectly named Rex Reason—argue that man is caught between the “jungle and the stars,” between the blackness of the lagoon and the whiteness of Anglo-Saxon achievement. Barton’s purpose is to bring the Creature out of the jungle, to force him to evolve; Barton is the classical eugenicist, bent on breeding out inferiority and “whitening” the lesser races.

[28] In contrast to Barton, Morgan is the reformed eugenicist. As Celeste Condit argues, after WWII, genetic science attempted to distance itself from the taint of eugenics, which was now linked to Nazism and the Holocaust in public discourse (90-91). Instead of advocating that breeding could create a superior human, reform eugenics promoted ideas concerning genetic health and well-being. Reflecting this stance, Morgan states, “We can learn from nature, help nature select what is best. We can make this earth a happier place by helping nature select what is best in us.” Morgan also represents the conflicted nature of genetic science in the 1950s, the manner in which definitions of health were as potentially racist as definitions of superiority. Morgan seems to oppose Dr. Barton’s cruel eugenic experiments, yet he passively agrees to assist in them because he has to “see for [him]self” what the outcomes will be. He insists (three times in the movie) that we are “between the jungle and the stars,” and argues for the importance of a positive environment over heredity. However, he never questions his own participation in the “whitening” of the Creature.

[29] In The Creature Walk Among Us, as in all of the films, the scientists venture out in a small boat in hopes of capturing the Creature. During this process, the monster accidentally douses himself with gasoline. He is set on fire by one of the crew and horribly burned (a punishment which also occurs to a much lesser extent in the first film). The lynching imagery here is hard to ignore, but in a moment of racist narrative logic, the lynching effects a positive, evolutionary change toward whiteness. The Creature proves highly adaptable; he is compared to an “African lungfish” that can survive in dry conditions by using an additional pair of lungs. After being burned, he loses his gills and becomes an air-breather, although he does not understand this fact and must be restrained by the scientists from entering the water. The lynching then is transformative rather than fatal; the violence is seen (at least initially) as therapeutic, forcing the black skin literally to peel away and reveal whiteness underneath. The Creature even participates in his own lynching by dumping the gasoline over his own head.

[30] The effect, however, is not to remove the Creature’s racial indeterminacy, but to introduce that indeterminacy into the white body/society. The Creature is taken out of the swamp and placed within, or more so, next to Dr. Barton’s home/compound. He is kept in a pen, next to animals, and is able to gaze at the men and at the white woman, Marsha, but not to interact freely with them. In the second half of the film, the Creature is basically benign, and the film would seem to be a narrative of assimilation; the Gill-Man has been converted from blackness and can “walk among us” but only in confined, set spaces determined by the white power structure.

[31] The film criticizes this message of assimilation by refusing to portray the Creature’s entrance into white masculine society in a positive light. All three male leads—Dr. Barton, Dr. Morgan and Grant—are roughly similar in physical appearance, representing the homogeneity of white patriarchal culture, a homogeneity which is deeply troubled since Barton, Morgan and Grant argue with and fight each other throughout the movie. Ultimately, Barton and Grant—but not the anti-eugenicist Morgan—are revealed to be more primitive than the Creature. Barton kills Grant in a fit of jealous rage, using the butt of his pistol to bludgeon his rival to death. The murder has a savage quality; Barton chooses to club Grant, rather than use the more technologically advanced weapon in this hand. At the end of the film, he finds himself running in fear from the symbol of the evolutionary potential of the “lesser” races to unseat white supremacy—the Creature—who has proven to be morally and physically superior to the supposed civilized doctor.

[32] The movie ends with the Creature returning to the ocean and to his death, since he will now drown, an ending that what would seem to be the traditional death of the tragic mulatto. However, the film does not show us the monster entering the water; the last two shots are of the Creature looking at the ocean and moving toward it, then the waves breaking against the shore. The final shot is important in that it complicates the dichotomy between the black jungle and the white stars that the film emphasizes to such a great degree by ending on a third possibility: the ocean.

[33] Throughout the film, water represents a kind of freedom from white, male dominance. After being taken from the Everglades, the Creature spends much of the movie trying to escape from the scientists and get back to the water, even after he has lost his gills. Marsha, the much-abused wife of Dr. Barton, says that “swimming is like being born again,” and she obviously uses the water as a refuge from her horrible husband. At one point, she dives too far underwater and experiences the “ecstasy of the deep”; delirious with pleasure, she strips off her scuba gear, only to be dragged to the surface by Morgan, the white male hero. In this way, the third film clearly foregrounds the connection that exists in all of the films between the Creature and the various female leads; they are both oppressed, and the water is their escape from that oppression. Even her name (Marsh-a) connects her to the Creature’s habitat.

[34] Most importantly, the rape narrative of the ethnographic horror film breaks down. Unlike in the other two films, the Creature’s primary goal is not to obtain the female lead—the white object of desire—but to reenter the water. In The Creature Walks Among Us, the threat of rape comes from Grant, a white man, who aggressively pursues and attempts to force himself onto Marsha. In a complete reversal of the typical narrative, the Creature interrupts the rape, thus saving Marsha and revealing white society to be savage and murderous. The dynamic of lynching tightens, becoming a closed circuit that excludes blackness. The rapist to be punished is a white man; the lynch mob who falls back into “justifiable” savagery is Barton, another white man. Barton attempts to reestablish the economy of demonization by reintroducing the racial Other as its traditional scapegoat; he takes Grant’s body and places it in the Creature’s pen in order to make it look as if the racial monster had murdered the white man. By doing so, he unwittingly releases the Creature who then seeks him out and kills him while conspicuously sparing Marsha and Morgan. He hurls the doctor from a balcony, and at that moment, the Creature, standing by a wicker chair and framed between ivy-covered columns, holds his former master over his head. The image recalls plantation homes, figuring the Creature’s revenge as a slave rebellion. His actions also free Marsha, who at the end of the film is liberated from her abusive husband.

[35] Many summaries of the film assume that, after this point, the Creature dies, that he returns to the water in which he no longer can survive. As stated earlier, the last image of we have of the Creature is on the beach, not in the water or on the land. He has returned to that interstitial space between the primitive and the civilized. He is a figure of racial hybridity who has rejected white modernity, and while he is a monster, his monstrosity is a rebellion against what is defined as civilized, masculine and white.

Racial Fusion: Monster on Campus and the Internalization of the Color Line

[36] While The Creature Walks Among Us challenges the evolutionary hierarchy of the rape narrative,Monster on Campus would seem to support it in overstated terms. The threat of the Caveman, the titular monster on campus, must be read in the context of Brown vs. the Board of Education, the film having been released only a few years after that landmark decision. James T. Patterson cites an article written in theAtlantic Monthly in 1956 entitled, “Mixed Schools, Mixed Blood,” which decries the possibility of a rise in interracial sexual relationships due to the increased interaction between white and black students (87). As Patterson notes, segregationists were eager to divert the blame for such “mixed matings” away from whites by invoking the “specter of sexually aggressive black males”(88). Monster on Campus clearly plays off of these racist fears and political tactics. One lobby card shows the Caveman’s bestial face looming over an university setting as two stereotypical college students—a young man and woman, holding hands and wearing collegiate style sweaters—run in fear; the same card reads, “Students victim of terror-beast” and ” Co-ed beauty captive of man-monster!”

Figure 3

[38] White womanhood is embodied by Madeline. She represents the pure, blond white woman—she wears white throughout the entire film and speaks in a kind of clipped, Bostonian accent—and is used to glorify white sophistication while buttressing views concerning the dangers of the “subhuman,” from which she must be protected. This threat is almost realized when the Caveman attacks her at the end of the film. Before a park ranger stops him, the monster gropes her and pulls violently at her hair. Earlier in the film, the Caveman assaults Molly, who—unlike Madeline—is a brunette and is thus not provided the full protection of white male society. Molly dies from fright, and the monster hangs her from a tree, by her hair. In this way, the iconography of lynching—a victim’s body hanging from a tree—is appropriated in order to bolster the fear of the black rapist; according to the movie, it is black men who “lynch” white women and must be punished.

[39] Yet, it is important to emphasize that ultimately the neandrathalic monster of this film is not a black student—none exist in the film—but Blake, the white professor. Early in the movie, he lectures his class concerning the perils of the evolutionary process. “Man,” he tells them, ” is not only capable of change, but man alone, of all creatures, can choose the direction which that change will take place.” He ends his lecture with a prediction that this evolutionary trajectory can have only two destinations: evolving to a state of being “far beyond what is now imaginable” or devolving into ” bestiality.”

[40] His warning, which frightens one of his female students, is borne out in the narrative of the film, as the Professor himself—the spokesperson for knowledge and science—is transformed swiftly into the murderous Neanderthal through accidental exposure to the radiated blood of a “living fossil,” a coelacanth. The “terror-beast” is not an external threat to the normality of white hegemony. The creature and the professor are one and the same; several times, Blake comments on how the beast is “within” him. At the beginning of the film, Blake states, “Sometimes I wonder, unless we learn to control our instincts we have inherited from our ape-like ancestors, the race is doomed.” Importantly, he uses the word “race” and not “species” to describe humankind, although he uses the latter term in a similar and subsequent speech to his class. The race in question is white and as “Blake” is revealed to be “Black,” the essence of white purity becomes deeply troubled.

[41] This problemitization of racial definitions is reinforced by radical changes in genetic science during the 1950s. Moving away from the older style of eugenic philosophy, many genetic textbooks during this period argued for the absence of “superior” races and the inconsequentiality or lack of meaningful racial divisions on the genetic level. A common idea expressed in these texts is that all races are intermingling and have been doing so since the beginnings of human life. According to Heredity, Race and Society, published in 1951, “Race mixture has been going on during the whole of recorded history…Mankind has always been, and still is, a mongrel lot” (Dunn 115). Theodosius Dobzhansky, in Genetics and the Origin of the Species, states, ” To the geneticist it seems clear enough that all the lucubrations on the ‘race problem’ fail to take into account that a race is not a static entity but a process…what is essential about races is not their state of being but that of becoming” (177). This “becoming” leads eventually to a state of “racial fusion” (Dunn 130), a point in the future when racial differences will disappear due to intermixing.

[42] In an even more fundamental sense, genetic science unhinged ideas concerning racial difference by questioning the nature of the body and the key metaphor of blood. The concept of blood is essentially traceable and linear; once an ancestor is labeled as black—certainly, of course, a vexed point of origin—the “one drop” can be charted as it passes through successive branches of a family tree, a history available through genealogical records. Genes, however, present a much more troubling source of embodiment. In the 1950s, with the discoveries concerning the workings of chromosomes and DNA, the body becomes a coded text, readable only by scientists and heredity counselors, if it could be understood at all. Genetic mutation is essentially random; mutation may occur due to radiation, a fear compounded by the threat of the atomic bomb.

[43] Through the popular discourse of genetic science, the body becomes imbued with a “somatic unconscious,” an invisible dimension that controls visible form; we may look “normal,” but our genes may not be. Within this unconscious level, the “abnormal” is repressed, although it still influences, even determines, the “normal”(Gonder 35). In a white supremacist society, the definition of the “abnormal” becomes linked to blackness; tellingly, harmful chromosomes, undetected in the body, were often referred to as “black genes,” and geneticists warned that almost everyone had one of these indicators of abnormality as part of their basic genetic make-up. The color line does not disappear but is instead internalized on the cellular level, in the somatic unconscious. The concept of racial difference becomes even more indeterminate as it becomes—or perhaps because it becomes—even more deeply embodied (Gonder 38-39).

[44] In this way, Prof. Blake/the Caveman is a passing figure. As constructed in the discourse of genetics and evolution that he himself teaches, his body has “mixed blood,” but he is not aware of it. Even as the evidence and the bodies pile up around him, he takes a surprisingly long time to realize his situation. After learning of his black heritage, Neil Kingsblood finds himself “in a still horror, beyond surprise now, like a man who has learned that last night, walking in his sleep, he murdered a man, that the police are looking for him” (Lewis 60). Blake experiences literally what Kingsblood fears metaphorically. The professor’s “blackness” is somnambulistic, compulsive, violent and beyond his control since it is internalized within his body. Importantly, his transformation into the Caveman is not seen as metamorphosis into a new state of being but the return to an earlier, essential condition. As the trailer for the film promises, “Evolution Reversed…See a man revert to a half-human anthropoid from the dawn of creation.” Right before his death, Blake states, “Every man is a product of the whole human race. The past is still with us.” In light of his statement, an earlier, flippant comment made by one of his colleagues takes on a new meaning: “You’ve got primitive species on your brain.” Blake and the Caveman are one and the same; the primitive, racial other, awakened by the radiated blood, is a part of his basic genetic make-up.

[45] The essential and unconscious quality of Blake’s racial hybridity is revealed by the innocuous nature of the cause of his transformation. The film begins with the Professor receiving a shipment containing a coelacanth, packed rather haphazardly on ice. This species of fish was thought to have become extinct but was discovered in 1938. Unfortunately, this particular specimen was not preserved. In 1952, another was caught, properly preserved and displayed to a fair amount of publicity. To the audience of the time, this famous fish might have signified a solid link between the prehistoric and the modern.

[46] In moving the fish, Blake places one hand underneath its body and the other, inexplicably, in the fish’s mouth. After cutting his hand on the coelacanth’s teeth, he clumsily plunges the open wound into the filthy, bloody water of the tank in which the fish was shipped and is thus contaminated and transformed. Blake later learns that the fish has been radiated in order to try to preserve it on its trip; atomic power—the possible source of devolution on a global scale as described earlier in the essay—is used for the routine purpose of preservation, as a substitute for a freezer. I repeat this process in detail in order to emphasize the mundane nature of the Caveman’s origins. In contrast to other scientist figures, Blake does not become a monster due to overreaching, or playing God. Dr. Jekyll consciously chooses to unleash Mr. Hyde in an attempt, however arrogant, to rid humankind of evil; Frankenstein defies God in order to create life; Blake just tries to move a fish. Later in the film, he manages to drip coelacanth blood into his pipe and smoke it. The trivial means by which Blake is transformed emphasize the permeable nature of the border between the civilized and the primitive, between white and black.

[47] As the representative of white male civilization, Blake realizes that he has been passing as white and that white “purity” is impossible. In fact, everything and everyone in the film is a potential racially mixed monster. When Samson, a loveable German Shepard owned by a student (played by white icon Troy Donahue), laps up the bloody water leaking from the defrosting fish, he devolves into an “antediluvian wolf”; he develops fang and becomes vicious. A dragonfly lands on the fish and quickly grows to gargantuan proportions. In this film, even the animals are passing. All it takes, fittingly, is one drop of blood to reveal their hidden but essential nature, bringing out what is already present, the non-white element that is part of the white body.

[48] While Monster on the Campus works to unsettle the racist evolutionary narrative by internalizing the threat, it also attempts to solve that threat through Blake’s “heroic” self-sacrifice. When Blake finally realizes that he is the Caveman—after spending a great deal of the film ignoring all of the obvious evidence pointing to him—he does not turn himself in but instead organizes his own lynch mob by purposefully (for the first time) transforming himself into the Caveman, thus forcing the police officers to shoot him. The ending presents racial fusion as the source of horror and absolves Blake of any wrongdoing. After he is dead, as is typical of such scenes, the remaining characters gather around the body and watch the transformation back into a now peaceful and innocent Prof. Blake. This conclusion seems to enact the removal of the hybrid from the white body and a return to racial purity.

[49] More so, the racial hybridity of the Caveman is not automatically or essentially oppositional to white male supremacy. As Wiegman argues in terms of lynching, sexual violence directed against women acts not only to demonize the black male but also to establish a means to express and justify white male fantasies; the white male can be both attacker and protector. In this sense, the hybrid nature of the Caveman in Monster on Campus asserts white masculinity against and through the fantasy of a primal, animalistic black sexuality, a strategy all too common in the 1950s. The rape imagery of the film, particularly the manner in which Molly is suspended by her hair, is often played for comic effect outside of the horror film. During this time period, the image of a Neanderthal man, wearing fur over one shoulder, carrying a club and dragging a woman by her hair—an act that strongly implies an ensuing rape—was a common sight in cartoons and comic strips. Other examples of cavemen were less openly misogynistic. B.C. was created in 1958 by Johnny Hart, whileRocky Stoneaxe (known as Peter Piltdown in the 30s and 40s) appeared in the back of Boy’s Life throughout the decade (Markstein). Of course, the most popular caveman of the time was V.T. Hamlin’s Alley Oop, whose strip began in 1933 and whose popularity during the 1950s is evidenced by the song of the same name, sung by the Hollywood Argyles and released in 1960. This song is only one example of a mini-genre of caveman-related music during the late 1950s. Other examples include Randy Luck’s “I was a Teenage Caveman”(1958), Jerry Coulston “Caveman Hop”(1959), and Tommy Roe’s “Caveman”(1960).

[50] Many of these primitive figures—whether comic or horrific—share an essential quality. They are large, strong, and brutish; they make up for their lack of sophistication with pure testosterone. The caveman is an image of pure masculinity, unfettered by the constraints of civilization. Like Playboy or “Philip Wylie’s philosophy of ‘Momism," he is a mode of resistance against the emasculating nature of feminized modern life. In fact, the term “Neanderthal”—during the 1950s and continuing to present day—has become synonymous with male chauvinism. In Giant (1956), Elizabeth Taylor’s character, Leslie, verbally rails against the sexism that bars her from the “man talk” of a political conversation; she states, “You gentlemen date back 100,000 years. You ought to be wearing leopard skins and carrying clubs.” As recently as July 2004, TV Guide cheered the cancellation of the most recent incarnation of The Man Show, stating that “once again, the Neanderthal era has come to an end” (20).

[51] The caveman as a vehicle for white male desire depends on hybridity, on the projection of white misogyny onto the black body, but it also depends on racial purity, on the ability to then simultaneously assert racial difference within the context of white male power. The number and range of examples above—from horror films to novelty songs—is evidence not of the ease with which racial difference is affirmed, but the difficulty, the need to continually reinforce the increasingly contested position of the white male.

[52] The tenuous nature of white supremacy is illustrated in the opening of Monster on Campus. The movie begins with a tracking shot of a set of busts in Blake’s lab, each one depicting a stage in human development, with the respective name included underneath. The first is a primate (who actually looks somewhat like the Creature and who is not given a name); the next is Piltdown man (who is included in the film even though he had been revealed to be a hoax in 1953), Java Man and so on. The next to last bust is Modern Man, whose face appears to be Anglo. The final plaque is empty, except for the label that reads, “Modern Woman.” The camera then tracks downward to show Blake and his fiancée, whose face is covered in plaster; at this point in the narrative, her identity is uncertain, a blank, just like the plaque on the wall. Blake says, “The female in the perfect state, defenseless and silent.” Madeline—made mute by white plaster—is to be the model for the Modern Woman; her face will be the finale of Blake’s evolutionary line up. Yet, her placement as the apex of male civilization also prompts Blake to give one of his many speeches concerning the essential savagery humanity has “inherited from our ape-like ancestors.” Madeline’s place in this ladder of progress is visually rhymed with the lowest position. Her plaque is empty but has a name; the first “subhuman” does not have a name but does have a face. Like Marsha in The Creature Walks Among Us, she is essential to white evolution, perhaps even the culmination of it, but is still connected to the dangerous primitive.

[53] After removing the plaster, Blake tells Madeline that her bust will “go at the end.” In response, Madeline tells him not to “make it so final” and that he is a pessimist; as someone who is already linked to racial hybridity through her connection to the primitive, she sees a future for humanity that Blake does not. In light of this beginning, the ending in which the racial fusion represented by the Caveman seems to be undone might be read in a different way. In the final chapter ofWhite, Richard Dyer describes the horror film as a “cultural space that makes bearable for whites the exploration of the association of whiteness with death”(210). As evidence, Dyer cites the pale hues of the vampire and the zombie. It is also possible to apply Dyer’s ideas to monsters such as the Caveman, who—in the tradition of the Wolfman and, interestingly, many female vampires—changes back into a fully human (i.e. white) state upon death. In light of Dyer’s comments concerning whiteness, it is possible to read the ending as equating this same purity with death, with nothingness, with the end of the narrative (both cinematic and evolutionary). The racially unmixed Blake—if he exists at all—is “pure” only at the beginning and the end of the film and this state of white male perfection is associated with evolutionary inertia and death.

Conclusion

[54] In his history of lynching, At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America, Philip Dray discusses the brutal murder of Emmett Till in 1955 and the subsequent involvement of the NAACP in the case. Dray describes the kind of hatred that the NAACP had to face: “Every Mississippi schoolchild already knew that the initials N-A-A-C-P stood for ‘Niggers, Alligators, Apes, Coons, and Possums’”(426). The films that I discussed in this essay seem to commit the same racist sin of equating the non-white male with the animalistic and the monstrous, as an imagined threat to white women that justifies the horrific violence of the lynch mob.

[55] While I am not claiming that these films are purely oppositional, I would argue that they take part in an important shift in the discourse of embodiment. During the 1950s, evolution and genetic science complicated the very definition of racial difference, especially in the overturning of simple biological determinism, and by doing so challenged the notion of racial purity crucial to the maintenance of white male supremacy. In these films, the primitive beast and the victimized white female refuse to stay fixed in the evolutionary temporal schema, and the male body is revealed to be something other than the paragon of evolutionary development. While these films certainly demonize the Creature and the Caveman, the alligator and the ape, it is white patriarchy that emerges as the real threat.

Acknowledgements. I want to sincerely thank Professor Gregory Jay, Professor Vicki Callahan and Professor Barbara Ley of the University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee for reading and commenting on this essay in its various drafts. Their input and guidance were instrumental in its development.

Works Cited

- Bederman, Gail. Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880-1917. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

- Condit, Celeste Michele. The Meaning of the Gene: Public Debates About Human Heredity. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1999.

- The Creature from the Black Lagoon. Dir. Jack Arnold. With Richard Carlson and Julie Adams. Universal, 1954.

- The Creature Walks Among Us. Dir. John Sherwood. With Rex Reason and Leigh Snowden. Universal, 1956.

- Darlington, C. D. Genetics and Man. New York: Macmillan Company. 1964.

- Darwin, Charles. The Descent of Man. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books, 1998.

- Dobzhansky, Theodosius. Genetics and the Origin of Species. New York: Columbia University Press, 1951.

- Dray, Philip. At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America. New York: Modern Library, 2002.

- Dunn, L.C. and Theodosius Dobzhansky. Heredity, Race and Society. New York: New American Library, 1952.

- Dyer, Richard. White. London and New York: Routledge, 1997.

- “Cheers and Jeers.” TV Guide July 11—17, 2004: 20.

- Erb, Cynthia. Tracking King Kong: A Hollywood Icon in World Culture. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1998.

- Gonder, Patrick. Like a Monstrous Jigsaw Puzzle: Genetics and Race in the Horror Films of the 1950s.Velvet Light Trap 52 (Fall 2003): 33-44.

- Gould, Stephen Jay. Evolution and Human Equality. Insight Video, 1987.

- ________________. The Mismeasure of Man. New York: W.W. Norton, 1996.

- Graves, Joseph L. The Emperor’s New Clothes: Biological Theories of Race at the Millennium. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2001.

- Hendershot, Cyndy. Paranoia, the Bomb and 1950s Science Fiction Films. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1999.

- Howell, F. Clark, et al. Early Man. New York: Time-Life Books, 1965.

- Lewis, Sinclair. Kingsblood Royal. New York: The Modern Library, 2001.

- Markstein, Don. Don Markstein’s Toonopedia: A Vast Repository of Toonological Knowledge. 5/12/03.

- Monster on Campus. Dir. Jack Arnold. With Arthur Franz and Joanna Cook Moore. Universal, 1958.

- Moore, Ruth, et al. Evolution. New York: Time-Life Books, 1962.

- Patterson, James T. Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Rony, Fatimah Tobing. The Third Eye: Race, Cinema, and Ethnographic Spectacle. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1996.

- The Revenge of the Creature. Dir. Jack Arnold. With John Agar and Lori Nelson. Universal, 1955.

- Wiegman, Robyn. American Anatomies: Theorizing Race and Gender. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1995.

- Williams, Linda. Playing the Race Card: Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle

- Tom to O.J. Simpson. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- Wolpoff, Milford and Rachel Caspari. Race and Human Evolution. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1997.