Smoke and Mirrors: Feminism, Figurality, and “The Vine-Leaf”

If one wishes to deceive a man, what one presents to him is the painting of a veil, that is to say, something that incites him to ask what is behind it. –Jacques Lacan, “What Is a Picture?”

Ignorance, far more than knowledge, is what can never be taken for granted. –Barbara Johnson, “Nothing Fails Like Success”

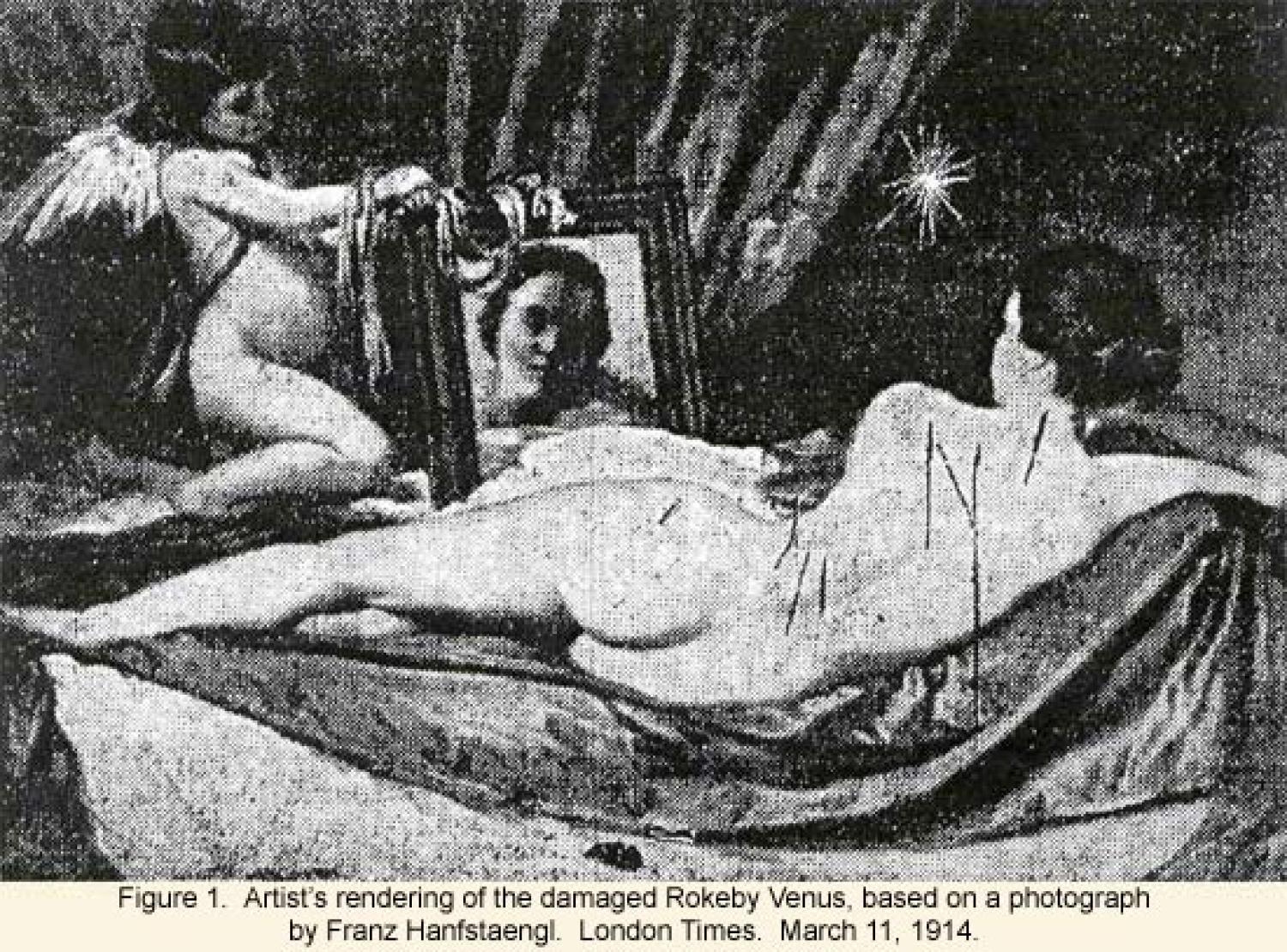

[1] On March 10, 1914, the National Gallery in London witnessed the vandalism of Diego Velázquez’s painting “The Toilet of Venus,” also called the Rokeby Venus. According to the London Times, a “prominent militant woman suffragist,” Mary Richardson, entered the gallery during regular visiting hours, broke the glass covering the work with a smallmeat chopper, and repeatedly slashed the canvas (figure 1). Her act was intended to protest the imprisonment of Emmeline Pankhurst, a leading activist and founder of the Women’s Social and Political Union. In a statement released after her arrest, Richardson explained: “I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history as a protest against the government” for its role in “the destruction of Mrs. Pankhurst and other beautiful living women” (“National Gallery Outrage,” 9).

[2] The National Gallery incident tells a story about the violence of representation and about a retaliatory violence against representation, a story that turns on an exchange between the female body and its image. It is perhaps not surprising that the Rokeby Venus should be a target of feminist complaint; indeed, Richardson could scarcely have chosen a more apt canvas for a protest whose paramount concerns were gender, mirroring, and mimesis. One of Velázquez’s best-known works, the Rokeby Venus depicts the Roman goddess of love and beauty as a nude woman, reclining on her right side with her back to the viewer, her pale skin offset by the red drapery of the background and the dark fabric beneath her. Richardson’s attack damaged the portion of the painting that depicts the woman’s back from neck to waist, leaving at least six vertical slashes in the canvas. In the upper left corner of the painting, untouched in the attack, a winged cupid supports a rectangular framed mirror, which reflects an image of the woman’s face, apparently returning her gaze (Click here for web link).

[3] The painting is, in this sense, a kind of rear-view mirror, whose optical trickery displays recto and verso of the female body at once for the viewer’s delectation. Its conventional trope, the female figure posed with a mirror, underscores the reflexive dimension of woman’s prescribed role as specular object. When, in the “vanity” of self-regard, the woman’s gaze turns back at the surface of the mirror, the erotic frisson of narcissism enlivens a thoroughly normative, not to say moralizing, tableau. In European painting, John Berger writes, “the real function of the mirror . . . was to make a woman connive in treating herself as, first and foremost, a sight” (51). The woman must watch herself being watched by men; she observes and enables her own positioning as an object of the male gaze. But while the Rokeby Venus is complicit in the social policing of gender and spectatorship, it also shows a distinct self-consciousness. Velázquez rhymes the frame of the painted mirror with the frame of the painting, as if the painting recognizes itself as a mirror image. As technologies of illusion, as image-machines, both “mirrors” reflect representation as such, promising the clarity of perfect mimesis while hinting at an inevitable distortion.

[4] Less than a year after the National Gallery incident, the New York-based Century magazine published a short story by María Cristina Mena titled “The Vine-Leaf.” Now recognized as a significant Latina figure in U.S. literature, Mena was born in Mexico City in 1893 and emigrated to New York at the age of fourteen; between 1913 and 1916 her stories, often regionalist pieces set in Mexico, appeared in U.S. magazines. Although “The Vine-Leaf,” Mena’s best-known text, does not name Mary Richardson or the Rokeby Venus, it organizes strikingly similar questions of gender and representation around a central image that,

despite the Century‘s rather different frontispiece (figure 2), cannot help but recall Velázquez’s famous work. The narrative concerns one Dr. Malsufrido, a Mexico City physician whose formidable reputation goes hand in hand with an unorthodox technique. Seeking to cure the mind as well as the body, he exhorts his young female patients to “describe me the symptoms of your conscience,” relating the sensational story of his first patient as dubious proof of his “discretion” (88). Many years ago in Madrid, he explains, a mysterious woman, hidden “beneath a veil as impenetrable as that of a nun,” asked him to remove a leaf-shaped birthmark from her back (88). The doctor recalls the incident years later when, visiting the home of a marqués, he is shown “the most mysterious and beautiful” of his host’s exotic possessions (90). Like the Rokeby Venus, this painting depicts a nude woman posed “with her back to the beholder . . . before a mirror,” although Mena’s model, unlike Velázquez’s, reveals on her back a vine-leaf birthmark (91). The marquésrecounts how he had found the artist, Andrade, murdered in his studio, sprawled beneath the canvas with a knife in his back. Because the painted mirror image of the woman’s face had been rubbed out by his assailant, the marqués says, the dying artist had added the vine-leaf to the painting to identify his killer. Finally themarqués explains that he obtained the painting as a gift for his wife, whom the Doctor instantly recognizes as his first patient, the woman of the vine-leaf.

[5] I place “The Vine-Leaf” next to the Richardson incident not only to note the historical coincidence of the vandalism with the publication of Mena’s text, but also to consider the uncanny mirroring between the two narratives. Like the National Gallery incident, “The Vine-Leaf” addresses the role of representation in women’s subordination and resistance–a resistance that begets aggression against the female body and against the effigy with which that body seems endlessly interchangeable. In both instances, aggression takes shape through cutting and disfigurement: the defacement of Andrade’s painting, the surgical mutilation of Mena’s veiled woman, and the slashing of the Rokeby Venus. Each act of disfigurement, in turn, constitutes a form of representation, a figure in its own right. In the National Gallery, we are told, every “laceration” and “gash” added to the Velázquez painting an extraneous figure, “clearly visible” in the Times‘s reproduction of the damaged canvas (9). And in “The Vine-Leaf,” the gesture of violent inscription recurs in the vandalism of Andrade’s painting, from which, as the marqués observes, the mirror image has been “obliterated”:

Observe that its surface is an opaque and disordered smudge of many pigments, showing no brush-work, but only the marks of a rude rubbing that in some places has overlapped the justly painted frame of the mirror. (91)

The damaged portrait yields another picture, whose excess meaning spills over the frame. Alluding to the surgeon’s artful knife, Andrade’s posture in death, “with a knife sticking between his shoulders,” presents the artist’s body as the killer’s signed canvas (92). Disfiguration becomes figuration; the cut becomes an inscription, acting out what Paul de Man terms the “disfiguration of metaphor,” or, borrowing Mena’s words for the damaged painting, the “opaque and disordered” quality of representation as such (120).

[6] “The Vine-Leaf” allegorizes its own reader’s work of interpretation, calling on three heuristic models–the criminal investigation, the psychoanalytic case study, and the work of literary analysis–each with its own fantasies of mastery and meaning. Mena shows how a certain “will to knowledge” inflects the production of the female body as a tissue of signs and as an object of epistemological desire (Foucault, 65). At once legible text and impenetrable enigma, the figure of thefemme fatale both feeds the lust for critical mastery and signifies what eludes it. Reading “The Vine-Leaf,” I will address such questions of epistemology and consider how Mena’s text may offer a response to notions of interpretive mastery found both in Richardson’s act and, I will argue, in contemporary feminist criticism. At a moment, no less than in 1914, when misogyny and heterosexism demand feminist intervention, reading Richardson and Mena together can help us to clarify what is at stake in certain intersections of representation, politics, and gender. In particular, the Richardson affair prefigures recent feminist attempts to reclaim and valorize the “living woman” over representation and discursive theory–attempts that, seeing representation as insidious falsehood, beget a kind of retributive violence against the specter of a deathly or dangerous figurality. In the context of a feminist criticism that often seems to demand the certainty of “lived experience” as the ground for political intervention, that is, “The Vine-Leaf” suggests the ways in which feminist reading practices may remain implicated in the phallocentric will to knowledge, and invites a new consideration of ambiguity and figurality.

What Is the Vine-Leaf?

[7] “It is a saying in the capital of Mexico,” Mena writes, “that Dr. Malsufrido carries more family secrets under his hat than any archbishop” (87). Thus announcing its explicit engagement with language and epistemology, “The Vine-Leaf” begins under the double inscription of “saying” and “secrets.” It will go on to examine some ways in which secrets are said, tracing the transferential narrative chains that link one person to the next. To say a secret, Mena suggests, is not to destroy it; instead, discourse constitutes secrets assecrets. “The Vine-Leaf” is a story about the rhetorical dimension of secrets, about their commodification and the consequences of their discursive circulation. Its narrative form insists on the text’s status as story–as, that is, a construction, a fiction, and an object of critical scrutiny. The marquéstells his tale to the doctor, who relays it to his female charges along with “the story of his first patient” (88). All this is related to us by an unnamed narrator; we hear the story, so to speak, through the grapevine.

[8] As Amy Doherty has noted, the narrative geometry of “The Vine-Leaf” resembles the double frame of Andrade’s portrait (xlii)–and that of the Rokeby Venus. The framed mirror within the picture’s frame echoes the structure of Mena’s text, whose frame story contains an almost abyssal sequence of narratives within narratives. What is the secret lodged in the innermost frame? “The Vine-Leaf” directs our gaze to a framed center only to reveal that space as empty; the mirror of Andrade’s painting is simply the placeholder for an effaced image. Our attention is deflected instead to the vine-leaf mark, whose narrative place is structurally symmetrical to that of the effaced mirror image in Andrade’s portrait. It stands at the center of concentric frames, holding out the secret the story cannot stop telling but will never fully reveal. Declining to reproduce the image of a face, the birthmark fills the gaping hole in Andrade’s composition through a displacement, a substitution of something else. “The Vine-Leaf” presents the birthmark in place of the “obliterated” portrait as the plot’s crucial clue: to learn the “secrets” of the vine-leaf is to grasp the meaning of the text. Alluding to the text’s preeminent sign, Mena’s title proffers part of the text as synecdoche for the whole, “the vine-leaf” for “The Vine-Leaf” (Ammons and Rohy, xxv-xxvi). And it is as a part that stands for the whole of a woman’s body that the vine-leaf also does its work in the murder mystery. “She who undoubtedly bore such a mark on her body” (92), we are told, must be Malsufrido’s patient and Andrade’s killer. In re-presenting the birthmark “painted” on a woman’s body, the birthmark that appears on Andrade’s canvas works as a kind of police sketch, the privileged clue in the murder mystery.

[9] Throughout the text, however, the vine-leaf exceeds its metonymic task. In its metaphoric function it signifies promiscuously, gathering “merely” symbolic meanings incidental to the demands of plot. It is not remarkable that both doctor and marqués fix their attention on the mark that “stains” the female body in life and art. But it is striking that both do so in exactly the same way. The marqués compares the painted birthmark to “a young vine-leaf in early spring” (91), echoing the doctor’s earlier reading of the mark as a “wine-red vine-leaf” (89). This repetition recurs in the doctor’s descriptions of both birthmarks, the painted and the embodied, as “staining a surface as pure as the petal of any magnolia” (89; 91). Why do the same phrases recur word for word? Why do the readings of the birthmark “accidentally” coincide? It is as if the birthmark is essentially a vine-leaf or a stain: there seems no room for error, no play of meanings. But in fact the opposite is true. Rather than removing the birthmark from the symbolic economy, these “coincidences” underscore the literariness of both the vine-leaf and “The Vine-Leaf.” This is a world shaped by the symmetries of literature, a realm in which figures proliferate.

[10] We are asked to believe that the vine-leaf is easily readable, but the project of reading it seems endless: like the ink blot of a Rorschach test, the vine-leaf finds its meaning in the observer’s desire. When the veiled woman asks the doctor for his help in removing what she calls a “blemish,” Malsufrido spares no rhetorical expense in the interest of flattery:

it seems to me a blessed stigma, Señorita, this delicate, wine-red vine-leaf, staining a surface as pure as the petal of any magnolia. With permission, I should say that the god Bacchus himself painted it here in the arch of this chaste back, where only the eyes of Cupid could find it. (89)

Bacchus and Cupid, red wine and stigmata, painting and magnolia petals–flush with allusion, this is literary language, which locates the birthmark in and as a kind of writing. The reading of the birthmark as a vine-leaf imposes meaning on the mute mark by recognizing–or misrecognizing–it as a signifier. The vine-leaf, however, is a “mysterious symbol” in a distinctly gendered language. The figure that “stains” the “pure” and “chaste” body of the woman reveals that body as anything but pure, showing the female body as the creation of Bacchus and the plaything of Cupid, already stained by eros and enjoyment. Alluding to the fig-leaf that in European art coyly signifies the primal couple’s–not to say the artist’s–shame at nakedness, Mena’s vine-leaf, as Elizabeth Ammons has noted, bespeaks Eve’s role in man’s corruption (146). Assumed after the knowledge of good and evil, the fig leaf suggests the consequences of the epistemological desire that we, no less than Eden’s couple, share. It marks the allure and the price of forbidden knowledge not only for Adam but also for the woman who must take the fall for man’s fall from grace. As such, the vine-leaf as fig leaf–or, we should say, as figureleaf–gestures toward the patriarchal myth that delegates to woman the task of embodying the body.

[11] This projection of materiality onto women also structures Hawthorne’s short story “The Birth-Mark,” in which a hapless scientist attempts to remove a birthmark from his wife’s face (see López, “‘Tolerance,'” 71-74). Prefiguring Mena’s concern with a woman’s marked body and the interpretive forces of masculine science, Hawthorne directs our attention to a bodily mark that seems, as the author elsewhere names his minister’s black veil, “a mysterious emblem” (Hawthorne, 102). Like that veil, Georgiana’s birthmark has no significance of its own; though called a “stain,” the mark is also a blank page, stained by each observer’s desire and transformed “according to the difference of temperament in the beholders” (119). To her husband Aylmer, the birthmark takes on sinister meaning:

It was the fatal flaw of humanity which Nature, in one shape or another, stamps ineffaceably on all her productions . . . The crimson hand expressed the ineludible gripe in which mortality clutches the highest and purest of earthly mould, degrading them into kindred with the lowest. (119)

For Aylmer, Georgiana’s birthmark allegorizes the high cost of earthly living, in a logic that makes femininity bear the weight of materiality and the consequences of desire. And the fruit of Hawthorne’s text does not fall far from Mena’s vine. Like the “blemish” of Mena’s veiled woman, the “defect” in Hawthorne’s tale is a signifier that represents on and as the female body “the fatal flaw of humanity,” the ineffaceable fact of “mortality,” and the degrading stamp of “Nature.”

[12] While “The Birth-mark” presents Georgiana’s blemish as emblem of an abject femininity, that mark also signals a certain incoherence in gender. In an incisive reading, Barbara Johnson argues that “The Birth-Mark” follows “the geometry of castration in Freud, in which the penis is the figure, or positive space, and the vagina the ground, or negative space” (19). The specter of the woman’s marked body thus violates the fantasy of woman as a blank page to be inscribed by man. Peggy Phelan has suggested that phallocentric culture posits the female body as an unmarked body, a body perceived as lacking in relation to man’s phallic possession. At the same time, Phelan writes, “cultural reproduction takes she who is unmarked and re-marks her, rhetorically and imagistically, while he who is marked with value is left unremarked, in discursive paradigms and visible fields” (5). Because she lacks the phallic mark, woman becomes culturallyremarkable or exceptional in relation to the masculine norm.

[13] As Tiffany Ana López has noted, “The Vine-Leaf” speaks provocatively to Phelan’s notion of the unmarked and re-marked female body—-a notion no less relevant to race than to gender. López’s reading of “The Vine-Leaf” in “María Cristina Mena: Turn-of-the-Century La Malinche” valuably addresses the relation between racial and gendered valences of the marked body, proposing that Mena’s treatment of the birthmark conjures a “fear of racial marking” uneasily joined with an effort to celebrate Mexican culture (32). In an American literature itself marked by the notion of the racially legible body, the treatment of hidden identity in “The Vine-Leaf” surely works a variation on racial/ethnic passing narratives. But the text itself may also be seen as “passing,” veiling over its own racial investments. Although López claims that themarquesa “is a woman of color” (33) and Doherty numbers the marquesa among Mena’s portraits of “upper-class Mexican women” (xl), Mena suggests that the marquesa, if involved in Andrade’s murder “in our own peaceful Madrid” (90), may be Spanish like the doctor and the marqués. Acting out its own thematics of visibility and invisibility, that is, “The Vine-Leaf” is both marked and unmarked by race. Where gender is concerned, López reads “The Vine-Leaf” as a narrative of female empowerment, arguing that Mena’s heroine “uses the means at her disposal to escape [her] status as marked, female, outlaw body” (“María Cristina Mena,” 31). The vine-leaf, López implies, is the sign of the female body’s cultural legibility and subordination; “staining” the female body, it literalizes the cultural marking of woman as Other. This “marked, female” body does not follow from Phelan’s first equation (men have the mark of phallic possession) but from her second (women are culturally marked as deviant). In the gendered paradox of the marked body, however, the vine-leaf also evokes marking in Phelan’s first, phallic sense.

[14] Like Hawthorne’s birthmark, Mena’s vine-leaf troubles the normative structure of figure and ground, but it does so by presenting a phallic signifier where there should be nothing to see. Recalling that the mark appeared freshly painted after Andrade’s murder, themarqués explains, “the blemish is not of the texture of the skin, or bathed in its admirable atmosphere. It presents itself as an excrescence” (92). On the female body, the birthmark appears as a “blemish” and an “excrescence,” an abnormal outgrowth or extraneous part. Should this “excrescence” not announce its morphological allusion plainly enough, we might recall a few lines from Robert Herrick: “I dreamed this mortal part of mine / Was metamorphosed to a vine” (26). While “The Vine-Leaf” lacks Herrick’s sly smuttiness, it is closer to “The Vine” than it may seem–willing to indulge, for example, the insistent double-entendre of perceptive “penetration” (91). So although the woman undressing in the doctor’s office promises a glimpse of a female body whose naked lack confirms its femininity, the doctor is also “astonished” by a woman endowed with something to lose (89). The perfectfemme fatale, it seems, comes equipped with a little something extra. As if recalling Mary Richardson’s curious nom de guerre, Polly Dick, “The Vine-Leaf” plays out the Polly-morphous perversity of a body at once female and phallic, aberrant and enticing (Diamond, 264-267 and Lyon, 120).

[15] Why then does the veiled woman demand the castrating cut? Her instructions to Malsufrido are clear: “For favor, good surgeon, your knife!” (89). If the birthmark means her peril, she must divest herself of what distinguishes her from other women and assume the coding of generic femininity. Her task is not to claim an unmarked body, but to return to a marking legible as the female norm. After all, the notion of the female body as unmarked is itself an effect of cultural inscription: woman is marked as unmarked, culturally legible as blank or lacking. Thus Mary Richardson’s attack on the Rokeby Venus, meant to distinguish life from art, in fact rendered the painting more perfectly representative of “woman,” whose fate in patriarchal ideology is always to bear the mark of the cut, to be figured by disfigurement. But Mena’s woman of the vine-leaf loses the phallic sign precisely to keep it. As Lacan reminds us, the phallus is not a thing but the transcendental signifier to which the male body only catachrestically refers. It is neither an “object” nor an “organ” but “the signifier intended to designate as a whole the effects of the signified” (Écrits, 285). In these less literal terms, the phallus designates a presence impossible in language, and castration names a loss that haunts all subjects in the symbolic order, but is displaced onto the female body. Mena’s vine-leaf, that is, alludes to a phallic authority that is constantly conflated with, but never reducible to, the contours of the male body. For the femme fatale, the removal of the “excrescence” may preserve her phallic authority, or the illusion of it, by allowing her to keep her secrets.

[16] What, then, is the vine-leaf? The sign that promises a key to Mena’s plot delivers both more and less. “That accusing symbol,” as the marqués names it, holds the enigmas that engage its readers’ desire (93). It appears both as the privileged signifier and as the simulacrum of an impossible truth. Emblem of an alluring knowledge, the vine-leaf anchors an erotics of reading and interpretation. The marked woman is desirable–to the reader as well as the doctor and the marqués –because she has what we want: she has the phallic knowledge of the “secrets” Mena’s text cannot say. Like Malsufrido, we read as fetishists, according to Octave Mannoni’s formula: “I know very well” (something is missing from “The Vine-Leaf”) . . . “but just the same” (I believe the answer is there) (Metz, 76).

Watching the Detectives

[17] With its therapeutic setting, effort to reconstruct the past, and attention to “symptoms of conscience,” “The Vine-Leaf” also offers a pointed allegory of psychoanalysis. Framing his first patient’s story as a case study, Malsufrido determines that “only some strong ulterior thought could have armed a delicate woman with such valor. I beat my brains to construe the case, but without success” (89). The mystery is the desire of the other, the “strong ulterior thought” whose clearest symptom is the vine-leaf. Practicing a kind of “talking cure,” the redoubtable Malsufrido rejects the method that “undertakes to cure a woman’s body without reference to her soul” and instead urges his patients to reveal the secrets of their desire (88). His technique combines religious ritual with modern psychology. Malsufrido, we are told, not only “looks like one of the early saints” (87), but also “captivates his female patients, of whom he speaks as his penitentes, insisting on confession as a prerequisite of diagnosis” (88). That trope of confession recalls the nineteenth-century transition from religious to scientific epistemologies that, as Foucault suggests, would combine “confession with examination, the personal history with the deployment of a set of decipherable signs and symptoms” (65). And psychoanalysis, of course, was among those new sciences. In “The Question of Lay Analysis” Freud outlines the difference between the psychoanalytic method and Catholic confession. “Confession no doubt plays a part in analysis,” Freud admits, but “in Confession the sinner tells what he knows; in analysis the neurotic has to tell more” (20:189). Unlike religious confession, psychoanalysis requires a reader, whose task it is to decipher what the subject conceals even from himself. The rise of “confessional science” is thus an entrance into a modern hermeneutics: what is confessed is not the truth, but a text in need of interpretation (Foucault, 66-67).

[18] Psychoanalysis is, in this sense, always a detective story, finding its proper end in the knowledge that may restore comparative order and health. As Peter Brooks has noted, both psychoanalysis and detective fiction strive to reveal obscurities and construct a complete story (285). Freud, to his credit, resists the roles of priest and policeman with a fine disdain for the world’s more pious laws; yet he also acknowledges that “the task of the therapist is the same as that of the examining magistrate,” not least when the therapist employs his own “detective devices” (9:108). Like any good analyst, Mena’s Malsufrido is both a doctor and an investigator, who will solve–to his own satisfaction if not entirely to ours–the case of the veiled woman’s identity and desire. Nor is the doctor Mena’s only detective. When Malsufrido notes that the marqués‘s story “promises an excellent mystery” (91), the marqués is eager to assist, supplying details of Andrade’s murder in the language of Sherlock Holmes: “while awaiting the police, I made certain observations” (92). True to the detective convention, the police are inept readers, easily outmatched by themarqués: “our admirable police are not connoisseurs of the painter’s art” (93).

[19] Sharing the roles of analyst and detective, we read “The Vine-Leaf” in hope of unraveling its mysteries. Like the doctor and themarqués, the reader is driven by what J. Hillis Miller calls an “hermeneutic desire,” fixed on the punctum of the vine-leaf (105). We strive to understand the painting that the marqués calls his “most mysterious” possession (90) and feel the doctor’s “curiosity . . . to see such a well-formed lady’s face” (91). Our pleasure lies in the tension and excitation of deferment, the anticipated moment of revelation, the oscillation of visibility and occlusion; it is what Roland Barthes terms an “Oedipal pleasure (to denude, to know, to learn the origin and the end)” (10). In plainest terms, “The Vine-Leaf” is the story of a strip-tease, a play of ignorance and knowledge, uncovering and covering, revelation and obscurity. The narrative both describes and performs a tantalizing unveiling, re-enacting the concealment and undressing of the unnamed woman in Malsufrido’s office. The vine-leaf is itself a veil that simultaneously covers and reveals the truth in this drama of concealment. As Mary Anne Doane explains in a discussion of veils in cinema, the obstruction is also a lure: “In the discourse of metaphysics, the function of the veil is to make truth profound, to ensure that there is a depth which lurks behind the surface of things” (54-55). In “The Vine-Leaf,” we tear away the veil only to reveal another obstacle to knowledge. The text’s opacity incites our desire to know and produces the illusion of meaning, the belief that there is something to know.

[20] If the strip-tease of Mena’s tale awakens our desire for knowledge, “The Vine-Leaf” is most interesting not in the way it rewards the careful reader, but in the way it refuses to do so. In fact “The Vine-Leaf” borrows the conventional rhetoric of detective fiction without its dedication to a mystery’s solution. We are led to believe that the marquesa killed Andrade, whom she knew intimately enough to pose in the nude, then apparently concealed her crime and her past with the removal of the identifying birthmark. When it falls to themarqués to relate the story of Andrade’s murder and its “solution,” the painted vine-leaf provides the central clue:

that color had been mixed and applied with feverish haste by a dying man, whose one thought was to denounce his assassin–she who undoubtedly bore such a mark on her body, and who had left him for dead, after carefully obliterating the portrait of herself which he had painted in the mirror. (92)

In the familiar language of detective fiction, the marqués supplies the elements of a conventional mystery’s solution–a description of the criminal, the method of the crime, her means of concealment, and the motivations of various parties. Yet these feats of “deduction” disguise his own implication in the events, his vested interest in the proceedings and his acknowledged tampering with the crime scene. Finding Andrade dead, he “had taken the precaution to remove from the dead man’s fingers the empurpled brush with which he had traced that accusing symbol” before the arrival of the police, becoming “the accomplice of an unknown assassin” in order to protect the artist’s model from prosecution (93).

[21] Seeking to solve a crime in which he admits he has played a part, the marqués is, like Oedipus, both detective and criminal. What value can his account have? And yet what evidence can, by proving him guilty, dispel the suspicion that somewhere a woman is getting away with murder? Freud writes, in “Dostoevsky and Parricide,” that “it is a matter of indifference who actually committed the crime; psychology is only concerned to know who desired it emotionally and who welcomed it when it was done” (21:189). In “The Vine-Leaf,” Andrade’s murder is welcomed by both the woman and the marques, as well as Malsufrido and the reader, who relish the unraveling of the mystery. With highly circumstantial evidence against themarquesa and no motive for the murder, this is a case in which, as they say, no jury would convict. Mena allows the possibility that the marqués knows his wife’s past, that he murdered Andrade himself, and that he painted the vine-leaf to incriminate the artist’s model–narrative strands that remain ambiguously alive at the text’s conclusion.

[22] It is not my intention to untangle the clues of “The Vine-Leaf,” as if a more thorough analyst could discover, among the evidence, what the doctor and marqués have overlooked. More useful than proposing how the text might be resolved is explaining the fact that it is not–which is to say, the ways “The Vine-Leaf” fails to complete the narratives of psychoanalysis and detective fiction, and the ways this failure may constitute its success. It is not that we cannot guess “what happened?” or “who is guilty?”, for Mena’s text allows the pragmatic reader to construct, as I have above, a more or less coherent story. But another, more accurate plot summary might simply say that “The Vine-Leaf” is about the failure of plot summary. InLooking Awry, Slavoj Zizek suggests that the detective plot takes as its central formal problem “the impossibility of telling a story in a linear, consistent way, of rendering the ‘realistic’ continuity of events” (49). The detective’s task is to tell that seemingly “impossible” story by organizing a jumble of clues into a satisfying narrative.

[23] “The Vine-Leaf,” however, provides no “‘realistic’ continuity of events,” instead taking “the impossibility of telling a story” as its conclusion. To “solve the case,” we must believe that the mystery of the veiled woman’s identity is nothing but a retelling of the murder mystery. To the text’s questions–whose birthmark was removed? who killed Andrade? who posed for his painting?–the answers must coincide. We must see three figures–the doctor’s patient, Andrade’s model, and the marquesa–as one woman, joined by the vine-leaf mark. Why then does the art connoisseur never recognize his wife as the “lovely body” in his favorite painting (93)? His blindness is that of misogynist culture, which insists, with the usual frat-house variations, that all women are alike in the dark: female bodies are essentially interchangeable. But perhaps there is something to this implausible blindness. In the absence of a continuous narrative linking artist’s model,marquesa and veiled woman, Mena’s female figures remain strangely separate. In a real sense the “lovely body” in the portrait is not the “modest” marquesa, nor is she the doctor’s unflinching patient. In Mena’s hall of mirrors, fragmented images seem never to coalesce under the pressure of narrative closure. The detective’s “solution” thus depends on a certain blindness: not a refusal to see what is before him, but a refusal to acknowledge the inadequacy of his vision and to see how much he cannot see.

The Subject Who Knows

[24] Refusing to reify femininity in a single portrait of “woman,” “The Vine-Leaf” becomes the textual equivalent of the Rokeby Venus, whose mirror reveals an eerie disjunction between the female body and its reflection. Discussion of the slightly blurred face in the mirror of the Velázquez painting has included speculation that the face was overpainted in the eighteenth century; that it functions as a screen for the projection of the viewer’s desire; and even, in an echo of “The Vine-Leaf,” that the face was left indistinct to protect the identity of the model (Brown, 183). The Times adds that when hung at Burlington House in the 1890s, the Rokeby Venus “was so obscured by dirt and old varnish that the face in the mirror could scarcely be distinguished” (“National Gallery Outrage,” 10). As observers have noted, Velázquez’s mirror violates the laws of optics; angled as it is, it cannot reflect the woman’s face, and yet a face appears–unreal, ghostly, disembodied, the face of another woman, which seems to originate in the mirror rather than reflecting the world outside it (Brown, 182 and Snow, 36-38). In “The Vine-Leaf” as well, the female figures remain dissociated; the doctor’s “knowledge” that they are all the same woman is an optical illusion. In a text structured by specularity, attuned to the obsessive fixation of the male gaze on the female body, what matters in the end is what is not seen. Although the doctor insists that the blemish “must be seen before it can be well removed” (89), the woman keeps “closely covered” (89) so that, Malsufrido says, “I did not so much as see her face” (88). The marqués in turn recalls “the unknown model, whom no one had managed to see” (92) and complains that the marquesa “will not look at the picture” (93). Psychoanalytic and detective narratives might present these occlusions as obstacles to be overcome by careful investigation, but “The Vine-Leaf” makes the “solution” to the mysteries depend on a failure of vision. Like the double portrait of the Rokeby Venus, it is a trick done with mirrors, making the shadowy images of three women seem momentarily to be one.

[25] That trick requires that the story turn from scopophilia to address a quite different register of meaning. Having fed the tendrils of a dozen readings, the vine-leaf is finally remarkable for what it does notsignify. If it serves to connect Malsufrido’s patient to Andrade’s model, it cannot complete the metonymic chain that would link the marquesawith the veiled lady. That revelation relies on sound, not sight: the doctor recognizes the marquesa‘s voice and the language of their previous encounter. The veiled woman had first refused to explain her wish to remove the birthmark, saying “Fix yourself that I am superstitious” (89). When he declines her payment, the doctor follows suit: “You are my first, and I am as superstitious as you” (90). Abandoning all pretense to what we might now call analytic detachment, he vows to share his patient’s desire, to enter into her imaginary. And later, at the tale’s conclusion, the marquesaconfesses her secret to the doctor when she recalls the language of that exchange: “I have been called superstitious,” she says, earning a facile promise from the doctor: “If you are superstitious, I will be, too” (93).

[26] As the magic word of the text, the word that “solves” the mystery of the woman’s identity, “superstitious” is displaced from person to person like the cut that uncannily slides from the Rokeby Venus to Andrade’s body and to that of Mena’s heroine. A superstition is an irrational belief, a conviction sustained in the face of contrary evidence–rather like the fetishist’s simultaneous recognition and disavowal–but “superstition,” as we know, can also name any thought outside the purview of Western rationalism (Doherty, xli-xlii). The culture of post-Enlightenment “reason” and “science” stereotypically attributes superstition to women, “primitives,” and ethnic Others (89). Yet Malsufrido’s superstition accomplishes what his science cannot, by “proving” the identity of the veiled woman. The governing principle of epistemology in “The Vine-Leaf” is finally this accidental, blind belief, not the deductive logic of the classical detective plot. Superstition, as the persistence of an idea beyond rational proof, turns out to enable what passes for empirical knowledge. Writing on the particular “superstition” of psychoanalytic transference, Zizek notes:

Transference is, then, an illusion, but the point is that we cannot bypass it and reach directly for the Truth: the Truth itself is constituted through the illusion proper to the transference–“the Truth arises from misrecognition.” (Sublime Object, 57)

Jane Gallop expresses the paradox of the transference in similar terms: “mastery of the illusions that psychoanalysis calls transference can be attained only by falling prey to those illusions, by losing one’s position of objectivity, control, or mastery in relation to them” (60). Though “mastery” and “Truth” are at best partial, they are also perversely dependent on illusion and error. In this sense, what Mena calls superstition may be another name for the effect of the transference. In “The Vine-Leaf,” transferential or superstitious belief leads Malsufrido to the effect of the truth; his weakness as a reader becomes his strength.

[27] Freud asserts that transference is always a form of love, and so is superstition itself (20:225). While superstition designates an irrational belief, it is also, as the OED notes, an “idolatrous or extravagant devotion.” In “The Vine-Leaf,” this love is figured as the magic through which a woman, in Malsufrido’s words, “may have power to bewitch an unfortunate man without showing him the light of her face” (93). “I had fallen in love with her,” he confesses earlier, “but I feared to appear ridiculous, having seen no more than her back” (90). Invoking the romantic clichés whose tendency to embarrass testifies to their cultural force, the doctor reports that he has had many patients but “loved none of them better than the first one,” for, he says, “the secret of the vine-leaf was buried in my heart” (90). Still, we should not conclude from his name that Malsufrido suffers badly; rather, taking a cue from that name’s other meaning, we might well attribute to him an impatient love that scarcely masks exploitative desire.

[28] Whatever “love” means here, the doctor’s love enacts a counter-transference that complicates the text’s allegories of psychoanalysis and reading. The transference from analysand to analyst is fundamentally bound up with authority and epistemology: Lacan explains transference with the formula “I love the person I assume to have knowledge” (Seminar, 67). The analysand’s transference–like that of the penitentes who listen, spellbound, to Malsufrido’s tale of “family secrets”–enshrines the analyst as “the subject who knows.” Transference is also an inherent dynamic of reading: the reader may place herself in the role of the analyst, taking the text as her analysand, or she may be the analysand who looks to the text as the authority, the “subject who knows” (Felman, 7). Malsufrido plays both roles, alternating between the analyst’s authority and the analysand’s desire for the knowledge of the other. And so does the reader of “The Vine-Leaf.” Aligned with the credulous listeners who follow his unfolding tale, the reader who accepts Malsufrido as the “subject who knows” is rewarded with thrilling, if incoherent, revelations. The doctor’s rhetorical questions–“Can you possibly imagine, Señora?”–and hollow congratulations–“What penetration of yours,Señora!”–frame his listener as a dupe, a supplier of cues (91). Even thepenitente‘s role in delivering the tale’s final insight seems only to underscore her subordination. Having unspooled “the story of his first patient” to the moment of truth, the doctor turns to his audience: “I ask you to try to conceive whose face I now beheld” (88). It falls to the listening woman to confirm Malsufrido’s insight in her own words: “was it not the face of the good marquesa, and did she not happen to have been also your first patient?” (93).

[29] How then can the feminist reader escape the galling role of thepenitente? Smart enough to see through this showmanship, we want to put ourselves in the doctor’s place, both to read as he does and to read what he cannot. Like Malsufrido, we struggle for mastery of the sign, pursuing both vine-leaf and “Vine-Leaf” to claim our own place as analyst, detective, “subject who knows.” Just as the marquésoutdoes the bumbling police and Malsufrido’s insight trumps themarqués, we want to surpass Malsufrido in narrating “what really happened.” That ambition, however, offers no escape from the text’s double bind. Each readerly effort of identification with the veiled woman requires an attempt to re-figure what has been disfigured–to elicit from the “opaque and disordered” mirror of Andrade’s mutilated painting the clarity of a face–at the cost of further disfiguration, misprision, and mystery. When, resisting the passive role of listener, we strive to secure our own authority, we find ourselves in the no less distasteful role of Malsufrido. When we deny his authority in order to acknowledge the unsolvable mysteries of the text, we risk reifying the myth of the feminine enigma. Even the feminist desire to celebrate Mena’s heroine as a resistant figure requires that we accept the doctor’s conclusions; we enter the transferential chain by acceding to his “superstition.” It is, in other words, the doctor’s recognition of themarquesa as his first patient that enables even a feminist reading to see one woman in the hall of mirrors. In identification with her, we share his fantasy and reply to him in the words of his own promise: “If you are superstitious, I will be too.”

Disfiguring Feminism

[30] Just as reading “The Vine-Leaf” against Malsufrido’s narrative authority risks reinstating that authority in another form, Mary Richardson’s gesture of protest at the National Gallery proved contradictory. Whatever else Richardson’s act may signify, it sought to denounce those who would revere an effigy of woman while debasing the original. “You can get another picture,” she reportedly said, “but you cannot get a life” (“National Gallery Outrage,” 9). As Janet Lyon has noted, her act was “an attack on representation–in particular the inadequacy of women’s representation in and by patriarchy” (121). Lyon’s formulation is astute: while Richardson’s target may have been the image of woman supplied by Diego Velázquez and, more broadly, by patriarchal ideology, her battle was fundamentally with representation itself. Viewing mimesis as a trap, she struggled to assert the difference between mere images and actual women, “mythological history” and real life. Art’s ability to mirror “living women” seemed to usurp the place of the real, elevating copy over original, mythology over truth, deathliness over vitality. For Richardson, then, the Rokeby Venus became a figure for figurality as such. Velázquez’ “picture of the most beautiful woman” provided a symbolic canvas on which to depict the fate of “beautiful living women.” The Rokeby Venus would be made to mirror Emmeline Pankhurst’s suffering, which in turn reflected the pain of all women. Yet in its “injury,” as the Times put it, the “mutilated” painting itself became a woman (8-9), inverting Richardson’s desire to champion the real woman over the image. Faced by an aesthetic tragedy, the Times personified the Rokeby Venus, deploring “a cruel wound in the neck” and “a broad laceration beginning near the left shoulder” (9). Enduring its “cruel wound,” the Velázquez portrait came to have a body: it was better than the real thing, more alive than life, more pathetic than “living women” and more deserving of sympathy.

[31] While Richardson’s story may remind us of the urgency of feminist intervention, it also suggests the impossibility of a reading not implicated in the structures it would address. Writing on the National Gallery incident, Elin Diamond offers a wry compliment: “Polly Dick brilliantly manipulates a sign to traffic in other signs” (267). True enough, but this is unfortunate for Richardson, who meant to signify her disdain for signification: “You can get another picture, but you cannot get a life.” Like Aylmer in “The Birth-Mark,” Richardson read by doing violence to her text; yet that protest against figurality became another act of figuration. Having recognized Venus as a figure of “mythological history” and invested the Velázquez painting as an icon for the suffragist cause, Richardson acted within the symbolic order she strove to repudiate. Since figuration is always disfiguring and disfiguration is inescapably figural, Richardson’s struggle against representation simply inscribed the Rokeby Venus with another, palimpsestic layer of signs. “The Vine-Leaf” itself reflects this dynamic in efforts of interpretation–by Malsufrido, the marqués, thepenitentes, and the text’s readers–that seek mastery through their own disfiguring figures.

[32] Mary Richardson’s protest also speaks to a certain persistent rhetoric in contemporary feminist criticism, which reframes the resistance to theory in gendered terms. A common version of this appeal, not unlike Richardson’s own, seeks to elevate “living women” over a system of representation imagined as essentially corrupt. In a range of recent feminist writings, bound in other respects to quite different ends, authors defend something called “reality” or “real women” over mere images–images construed not only as inferior substitutes for what Richardson called “beautiful living women,” but also as themselves inimical to women. Real politics, by and for real women, the argument goes, requires a focus on “reality” because only “reality” can provide the unassailable ground, the experiential truth, on which social change depends. Representation is seen as inadequately political, divorced from what certain activists like to call, without acknowledging its status as trope, the ostensibly anti-tropological dimension of politics “on the street.” Such positions, of course, have a long history. In a 1989 essay, for example, Jane Tompkins took “theory” to task for the repression of women’s lived realities–that is, a blindness to “the female subject par excellence, which is her self and her experiences” (135), and Barbara Christian in the same year portrayed a “disembodied” (230), abstract “theory” as deathly and inert, in contrast to the vitality of “my own life” and “folks who like me also want to save their lives” (235). The same logic informs the infamous recent essay in which Martha Nussbaum assails Judith Butler for elevating discursive analysis over “real bodies” and “real struggles” (37). Butler’s work, she argues, represents “the virtually complete turning from the material side of life, toward a type of verbal and symbolic politics that makes only the flimsiest of connections with the real situation of real women” (38).

[33] This appeal to the truth of “life” over the putative lies of representation, this defense of “real women” against post-structuralist feminist theory, demands certainty as the precondition of political intervention. Laboring to fix the boundary between reality and mimesis, another strand of this discourse rejects post-structuralist feminists’ acknowledgement of contingency. Susan Bordo accuses deconstruction of harboring a “fantasy of escape from human locatedness” (226), enabled by a rhetoric of indeterminacy in deconstructive readings that “refuse to assume a shape for which they must take responsibility” (228). And again, in Teresa L. Ebert’s polemic against what she terms “ludic feminism,” questions of undecidability are deemed “language games” (196) in contrast to “objective social reality” (59). Indeterminacy, Ebert maintains, is politically regressive because it obscures the “relation between discursive and non-discursive” (29-30)–a notion that substantially replicates Mary Richardson’s 1914 attempt to distinguish between “living women” and “mythological history.”

[34] These arguments, seeking to dissociate “real life” from representation and insisting on interpretive or political certainties, constitute a will to knowledge not unlike the patriarchal gesture that “The Vine-Leaf” anatomizes. Both Richardson’s remarks and Mena’s “The Vine-Leaf,” I have suggested, prefigure such contemporary feminist issues as they examine the masculinist framing of the female body, the politics of violence, and the stakes of representation. Yet the two texts offer antithetical models of feminist intervention: one hostile to representation and insistent on certainty, the other seeing figural indeterminacy as integral to feminist strategy. In her assault on the Rokeby Venus, Richardson may seem to occupy the position of Mena’s heroine, who arguably disfigures a painting for reasons both personal and political. In each case, the disfigurement of the image is a retribution for, and a preemptive strike against, a real or metaphorical violence seen as inherent in representation. But it might be more accurate, however different their aims, to align Richardson with Mena’s calculating Doctor Malsufrido–the relentless seeker of realities, the authority untroubled by uncertainty, the investigator for whom the “lovely body” of a real woman always trumps mere pictures. Although Richardson pursues the disfigurement of an image and Malsufrido, his surgery notwithstanding, would reconstitute the image in order to learn its secrets, both grasp for an authority imagined as beyond the world of signs.

[35] Richardson, that is, exemplifies what we might call the feminist will to knowledge, an old notion of mastery and meaning nominally in the service of new politics. As we have seen, both Richardson and Malsufrido reenact the gestures that they struggle against: for Richardson the figurality inherent in the repudiation of figurality, and for Malsufrido the “superstition” and countertransference that both enable and erode analytic authority. Much as Richardson rejects “mythology” to erect a new myth, the feminist resistance to representation also bears the stain of rhetoricity, desire, and indeterminacy. The notion of “real life” it champions is in fact less “real”–more fantasmatic, more indebted to willful blindness–than the “symbolic gestures” it would supplant (Nussbaum, 38). Moreover, the denial of uncertainty, of what escapes critical mastery, by feminist criticism constitutes a suppression of difference fundamentally no different from that of institutional misogyny and heterosexism. It goes without saying that the fate of women, individually or collectively, can be neither secondary nor insignificant to feminist theory. But such “political” matters are so inextricably bound up with discursive and ideological formations that any effort to cordon off a sacred zone of “real life” must undermine the possibility of meaningful feminist criticism across a broad range of issues, including the material concerns that effort would prioritize.

[36] How, then, might we read differently the figure of a disfigurement that has “overlapped the justly painted frame”? Who can look in the mirror of Andrade’s painting and see in its “opaque and disordered smudge of many pigments” something other than a crude erasure or the projected image of her own reflection? Mena’s text provides one alternative reading position in its ungendered narrator, whose zest for storytelling is surpassed only by her/his propensity for digression. Malsufrido’s renown, we are told, stems from “a legend that he physicked royalty in his time, and that a certain princess–but that has nothing to do with this story,” and from his resemblance to one of the saints, although, the narrator confesses, “I’ve forgotten which one” (87). Structured by distraction, circuitousness, not-knowing, this frame story does not return at the conclusion of the tale, signaling in its incompletion the possibility of a more open reading.

[37] Indeed, Mena’s failure of closure suggests a refusal of closure–a case against closure, against literalism and certainty, and against the will to knowledge that, like Malsufrido’s, deems figurality, indeterminacy, and the play of signs solely as obstacles to be overcome. Surely no reading can fully escape the desire for clarity and mastery, just as no reading can fully attain those aims. Given this double impossibility, perhaps the most vital knowledge is that of not knowing. In the poem “Brazil, January 1, 1502,” Elizabeth Bishop describes the Portuguese conquistadores who, armored by their expectations of the new world, “came and found it all not unfamiliar” (92). There is always something of the conquistador in the will to knowledge, even when baffled by a textual surface that perpetually reconstitutes itself. Against such campaigns, “The Vine-Leaf” insists on the role of superstition–desire, transference, coincidence, as well as ideology–in every reading. If the effect of a satisfying solution to the text’s mysteries is never more than a trick of smoke and mirrors, the truth the text does advance is that of the structuring role of falsehood in any truth. The “impenetrable” veil of “The Vine-Leaf” lifts to reveal another veil, like the “hanging fabric” of jungle through which, Bishop writes, the conquistadores press, in endless pursuit of the women “retreating, always retreating, behind it” (92).

Acknowledgements: For their valuable assistance, I thank Ellen Berry, Amy Doherty, Ilana Nash, Sarah Seidman, and Joan Trapnell; the staff of the University of Vermont’s Bailey-Howe Library; and the faculty writing group at BGSU’s Institute for the Study of Culture and Society.

Works Cited

- Ammons, Elizabeth. Conflicting Stories: American Women Writers at the Turn into the Twentieth Century. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- —- and Valerie Rohy, eds. American Local Color Writing, 1880-1920. New York: Penguin, 1998.

- Barthes, Roland. The Pleasure of the Text. New York: Hill and Wang, 1975.

- Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. New York: Penguin, 1972.

- Bishop, Elizabeth. The Complete Poems 1927-1979. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1979.

- Bordo, Susan. Unbearable Weight : Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. Berkeley : University of California Press, 1993.

- Brooks, Peter. Reading for the Plot. New York: Knopf, 1984.

- Brown, Jonathan. Velázquez: Painter and Courtier. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.

- Christian, Barbara. “The Race for Theory.” Gender and Theory: Dialogues on Feminist Criticism. Ed. Linda Kauffman. New York: Blackwell, 1989. 225-37.

- de Man, Paul. The Rhetoric of Romanticism. New York: Columbia University Press, 1984.

- Diamond, Elin. “Polly Dick and the Politics of Fisicofollia.” Theatre Research International 24:3 (1999): 264-67.

- Doane, Mary Anne. Femmes Fatales: Feminism, Film Theory, Psychoanalysis. New York: Routledge, 1991.

- Doherty, Amy. Introduction. The Collected Stories of María Cristina Mena. Ed. Doherty. Houston: Arte Público, 1997.

- Ebert, Teresa L. Ludic Feminism and After: Postmodernism, Desire, and Labor in Late Capitalism. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996.

- Felman, Shoshana. “To Open the Question.” Literature and Psychoanalysis: The Question of Reading: Otherwise. Ed. Felman. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977. 5-10.

- Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality: Volume I. New York: Pantheon, 1978.

- Freud, Sigmund. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Trans. and ed. James Strachey. 24 vols. London: The Hogarth Press, 1953-74.

- Gallop, Jane. “The American Other.” The Purloined Poe: Lacan, Derrida, and Psychoanalytic Reading. Ed. John P. Muller and William J. Richardson. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988. 268-82.

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Tales. Ed. James McIntosh. New York: W. W. Norton, 1987.

- Herrick, Robert. The Complete Poetry of Robert Herrick. Ed. J. Max Patrick. New York: New York University Press, 1963.

- Johnson, Barbara. The Feminist Difference. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Lacan, Jacques. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XX. Ed. Jacques-Alain Miller. Trans. Bruce Fink. New York: W. W. Norton, 1998.

- —-. Écrits: A Selection. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: W. W. Norton, 1977.

- López, Tiffany Ana. “‘A Tolerance for Contradictions’: The Short Stories of María Cristina Mena.” Nineteenth-Century American Women Writers. Ed. Karen Kilcup. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1998. 62-80.

- —-. “María Cristina Mena: Turn-of-the-Century La Malinche, and Other Tales of Cultural (Re)Construction.”Tricksterism in Turn-of-the-Century American Literature: A Multicultural Perspective. Ed. Elizabeth Ammons and Annette White-Parks. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1994. 21-45.

- Lyon, Janet. “Militant Discourse, Strange Bedfellows: Suffragettes and Vorticists Before the War.”differences 4:2 (1992): 100-132.

- Mena, María Cristina. The Collected Stories of María Cristina Mena. Ed. Amy Doherty. Houston: Arte Público, 1997.

- Metz, Christian. The Imaginary Signifier: Psychoanalysis and the Cinema. Trans. Celia Britton. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982.

- Miller, J. Hillis. Hawthorne and History. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1991.

- “National Gallery Outrage.” London Times. 11 March 1914. 9-10.

- Nussbaum, Martha. “The Professor of Parody.” The New Republic. 22 February 1999. 37-45.

- Phelan, Peggy. Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. New York: Routledge, 1993.

- Snow, Edward. “Theorizing the Male Gaze: Some Problems.”Representations 25 (1989): 30-41.

- Tompkins, Jane. “Me and My Shadow.” Gender and Theory: Dialogues on Feminist Criticism. Ed. Linda Kauffman. New York: Blackwell, 1989. 121-139.

- Zizek, Slavoj. Looking Awry: An Introduction to Jacques Lacan through Popular Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991.

- —-. The Sublime Object of Ideology. New York: Verso, 1989.