Performing the Closet: Grids and Suits in the Early Art of Gilbert and George

[1] Over the past two decades, British artists Gilbert and George have made enormous and colorful photographic art works depicting nude or semi-nude men alongside multiple self-portraits. Large pictographs from the 1980s show vivid cartoon-like penises; larger-than-life-sized images from the 1990s depict the artists themselves, stripped nude, mooning the audience. Such exploration of homoerotic subjects has been a central theme of the artists’ work over the past two decades, and art critics have introduced the topic of homosexuality into discussions of their art, despite the artists’ downplay of its importance. The open attitude of 1990s art criticism and the evident sexuality of Gilbert and George’s recent art have, nonetheless, failed to initiate an analysis of their early works from a gay perspective. The non-sexual subjects of their early photographs (1970-1977) and the homophobic atmosphere of British society of that time led the mainstream art press to fit the artists into heterosexual molds.1

[2] Art enthusiasts eagerly accepted the experimental new art and the original stylization of self put forth by the young Gilbert and George, but did not acknowledge the sexual preferences of the artists who produced it. Through ignorance or intentional neglect, these 1970s journalists failed (or refused) to notice the sexual dynamic of Gilbert and George’s earliest artistic endeavors.2 And yet, despite the press’s silence on the subject, Gilbert and George themselves did not seek to hide the nature of their relationship: they spoke of “queer-bashing” and dancing together at bars in a 1974 interview, and they posed holding hands or partially embracing for photographs taken by Cecil Beaton the same year. Interestingly, the interview remained unpublished and the photographs out of view until 1997! It would seem, then, that being gay in Britain in the 1970s involved a complicated relationship with the closet — one could live simultaneously inside and outside its limiting walls.

[3] In this essay I look carefully at the early art of Gilbert and George (1970-1977) and at their contrived public appearance to understand their complex relationship to the closet during these years. Not only do I find points of comparison between Gilbert and George’s choice of subject matter and a gay identity (or as John Clum has called it “a closet sensibility”). I also suggest that the metaphor of the closet parallels the artists’ repeated use of the grid in their art and the grid-like, conformist strategies of their public appearance.

[4] The closet stands as a metaphor for the silence of secrets, the upkeep of the status quo, and the distinction between private and public, inside and outside. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick labeled the closet “a shaping presence” in the lives of gay people, and John Clum noted that “the closet is less a place than a performance — or series of performances, maintained by the heterosexist wish for, and sometimes enforcement of, homosexual silence and invisibility.”3 The closet shields gay men and women from persecution, discrimination, and isolation by forcing them to pretend, play-act, and remain silent. In consequence, the closet divides and isolates gays, urging them to deny their desire.

[5] Grids contain images within rigidly defined units much as closets confine gayness into compartmentalized private lives. Resistant to narrative, grids equalize, control and contain. They reduce everything to vertical and horizontal uniformity and draw attention to flat surfaces. Grids present an all-over composition and imply conformity, underlying order, and interchangeability. In a similar way, a life in the closet forces gays to assume anonymous, uniform public personae. The grid is a visual structure that, as Rosalind Krauss has written, “announces modern art’s will to silence, its hostility to literature, to narrative, to discourse.”4 The grid’s “will to silence” directly parallels the silence of the closet. The silence of others functions as an active, constructing force in the lives of gay people. The silence of the grid denies narrative, equalizes units, and neutralizes art’s potential messages.

[6] Gilbert and George understood the anti-narrativity, the silence, inherent in the modular system of the grid. They gradually broke down the grid’s equalizing powers and constantly modified the grid’s uniformity without rejecting its structure. At times they respected the divisiveness of the grid and limited their images to its small compartments, while at other times they spread their pictures into several units or spaced their rectangular photographs crookedly on the wall. But the grid always remains. It can be found in the repetition of their earliest performance and in their most recent photo-pieces. In fact, the repetitiveness and stability of the grid filters into the artists’ stiff public image, their regulated suits, and unchanging daily schedules.

[7] Another aspect of the grid that parallels the closet is its screen-like quality and distinction between real and perceptual. A screen distances inside from outside, surface from depth. It protects a person from what is on the other side of the screen yet prevents him or her from attaining it. In Gilbert and George, the distinction between “real” and “perceptual” is unclear because they say that all their art is artificial (i.e. the opposite of real) yet they work from photographs of the “real” world. The indexical process of photography acts as a first type of screen between these two categories — real and perceptual — because the camera frames and distorts its images in a way that resembles vision but does not copy it. Although most critics have explained the grid as an incidental by-product of Gilbert and George’s work, one perceptive writer suggested the grids may act as “a barrier between the observant person and the confessions of Gilbert and George.”5This protective screen acts like the closet that allows a gay man to hide the aspects of his lifestyle that fail to conform to societal norms. Like the closet, the gridded squares create a distance between the artists depicted within them and their audience.

[8] A preliminary example from Gilbert and George’s oeuvre will elucidate the interconnection I see between grid and closet and prepare the way for further investigation.

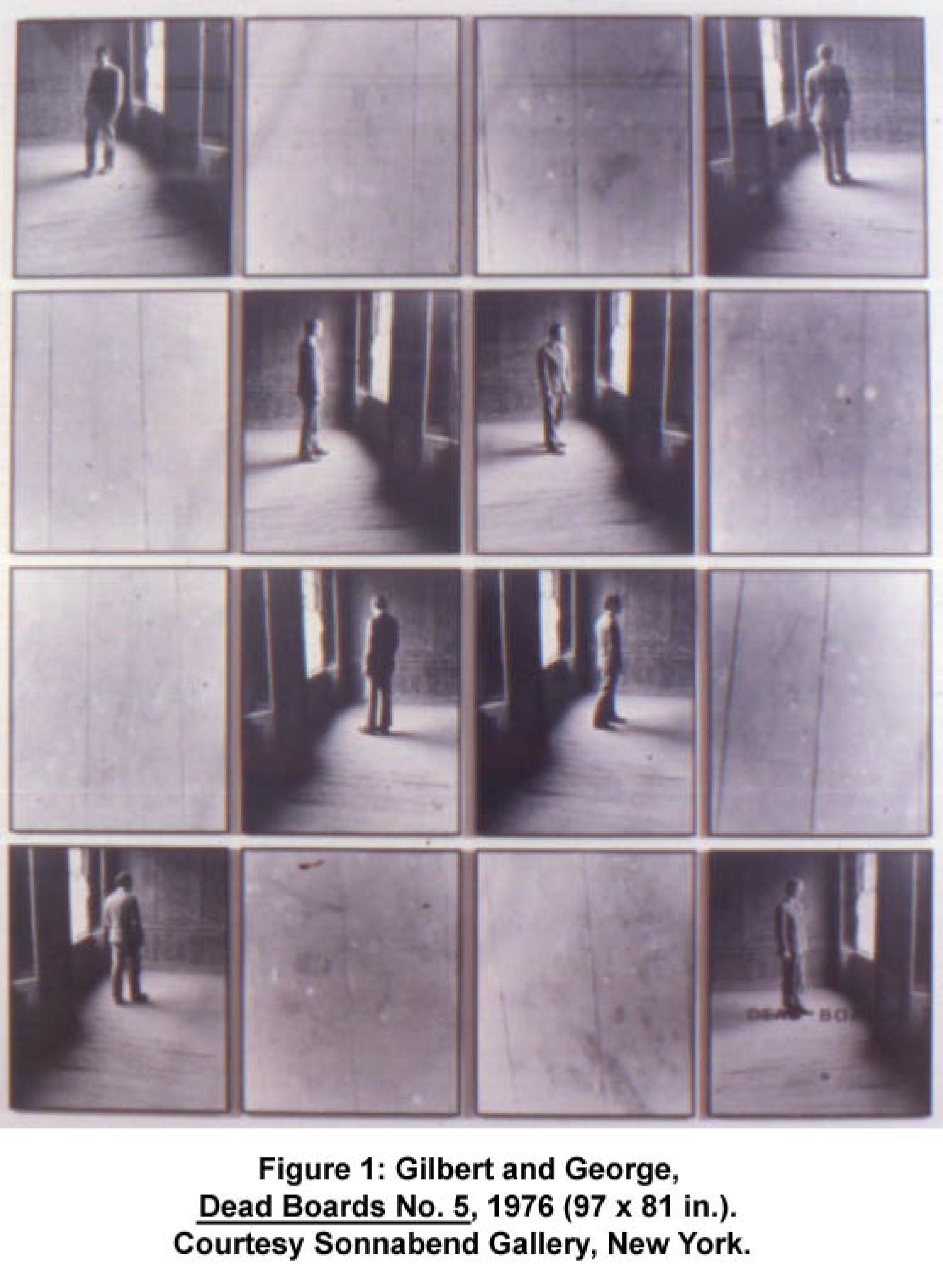

In a 1975 series entitledDusty Corners, and a 1976 series called Dead Boards, the artists photographed each other blank-faced in empty rooms (figure 1). Close-up shots of wooden floor planks are paired with gridded windows and faraway images of the artists. Gilbert and George never appear together in the same rectangular segment of these gridded photographs, they rarely face each other or the camera, and their faces convey no emotion. They walk aimlessly about the room, the camera freezing their steps in time and capturing the endless persistence of their isolation.6The repeated imagery and the lonely, introspective mood of the work hints at the artists’ struggle with the closet, a concept that divided gays in Britain during the seventies “liberation” years. While activist gays wanted to announce their sexual preferences publicly, more conservative homosexual men continued to lead “double lives.” Gilbert and George, whose homosexual relationship had not yet been made public, may have struggled with the desire to “come out” through their art. Their two year examination of empty rooms and their use of a strict grid pattern (coming at a transitional moment in their oeuvre) demonstrate an awareness of the prison-like qualities of the closet.

[9] This literal example of the relationship between grid and closet begins an analysis of the artists’ early works and public self-representation. In their nature Photo-pieces of 1971 the artists appear in full suits and ties, walking through English parks, posing as statues, and enjoying the landscape.7 This series consists of multiple, small black and white photographs in similar sized frames arranged unevenly on the wall. The prints represent inconsistent quality and show a certain studied sloppiness or hand-made aesthetic. Intimate in size, they hang in seemingly haphazard groups of as few as eight or as many as fifty and depict repeated close-ups of the artists walking or posing in outdoor settings (usually together but sometimes separately), close-ups or far away images of trees, lakes, and grass. In these Photo-Pieces, the artists did not employ a strict grid arrangement, and the photographs hang on the wall in a seemingly random fashion. Logic and order prevail, however, due to the repetition of images throughout the pieces and the grouping of horizontal and vertical images. In one of the nature photo-pieces, for example, the horizontally-oriented photographs depict the artists in nature, while the vertical ones show unpopulated park scenes. In another, seven horizontal photos balance seven vertical ones.

[10] In a different series from this time, in which the artists photographed themselves getting drunk, the grid seems totally ignored. In one of these works entitled Smashed, 1972 (figure 2), the pictures themselves create a sense of chaos in their tilted arrangement on the wall and blurry, out-of-focus scenes. The photographs have a hand-made, even sloppy, quality about them and are printed crookedly and hung diagonally or upside down to create fun-house mirror effects. The viewer regards the group of pictures as if through the blurred vision of the inebriated. Order and repetitiveness become apparent, however, when one notices that the same negative has been reproduced ten times, and that the images are all same-sized rectangles. These earliest photo works, the nature and drinking series, while not employing a strict grid pattern in their arrangement on the wall, do suggest order and repetition. In addition, although these early works make no explicit reference to gay desire, I suggest they point to coded signifiers of gay identity.

[11] When considered in the context of England’s socio-cultural climate of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Gilbert and George’s nature and drinking pieces, for which they visited several different London pubs and parks parallel activities of the British gay liberation movement. Jeffrey Weeks has discussed the changes in gay activism as a result of the 1967 British Wolfenden Report that made homosexuality legal between consenting adults. This political validation of homosexuality encouraged public demonstrations for gay rights as part of a new, activist gay liberation movement. The Gay Liberation Front, one of the most important gay groups at this time, sought the right to be served in traditional, old-fashioned London pubs and argued that “gay” bars exploited and cheapened them. In 1971, the same year that Gilbert and George began their drinking pieces, GLF members held demonstrations and sit-ins at two London pubs, the Colville and the Chepstow in Notting Hill Gate until they were served.8Although no direct connection has been made between Gilbert and George’s drinking pieces and the GLF’s activities, (and though I understand that being homosexual in Britain did not necessarily mean being a gay activist), the artists admitted to frequent drinking, dancing together at bars, and getting into bar fights with “skinhead types” or “lorry drivers” in the early seventies.9 They claimed, “people seemed to find our stance a bit aggressive,” and while neither artist elaborated on the particular nature of their “stance,” Gilbert commented that they sought “freedom,” a remark that associates their pub experiences to the gay sit-ins.

[12] In addition to pub resistance, the GLF hosted “gay days” defined as “picnics and celebrations of gayness in public parks” to assert their right to use and enjoy London parks along with their “straight” compatriots. These picnics took place in middle-class neighborhoods such as Primrose Hill and working class sections of the city like Finsbury Park, Battersea Park, and Victoria Park. Gilbert and George’s contemporary self-portraits in parks may relate to this public assertion of gay rights without explicitly connecting them to the GLF. In their own words they described a run-in with homophobic skinheads in the Finsbury Park neighborhood where they lived.10 In their nature scenes, the artists appear side by side, as a couple, in a public park.

[13] The positive, public activities of the GLF to gain greater gay rights could not remove the societal stigma and self-destructive attitude of many gay men and women forced to live under extreme oppression. Although homosexuality became legal, public display of affection between same sex couples remained illegal, and many British people continued to denounce homosexual acts as immoral and corrupt. In a small, hugely popular booklet published in 1974 entitled With Downcast Gays, Aspects of Homosexual Self-Oppression, authors Andrew Hodges and David Hutter described the self-defeating attitude of many British gays. Self-hatred among homosexuals, they wrote, had become unconscious and automatic. Gilbert and George’s three year exploration of the effects of alcohol points to a similar self-destructive tendency. Numerous photographs depict their blank, bleary-eyed faces in the company of empty bottles and glasses.

[14] Ironically, these drinking pieces give evidence of role-playing and parody. In later interviews, Gilbert and George confessed that although they often drank excessively during these years, they were not drunk when making the images. “They were very contrived pieces, very handmade,” claimed the artists, suggesting perhaps that the self-destructive stereotype of the gay man could be imitated or performed.11 The techniques afforded by photography such as blurring, double exposure, darkening, and unusually tilted compositions, allowed the artists to imitate the feeling and effects of alcohol while remaining sober.

[15] By the end of the drinking series, the artists had adopted a more rigid arrangement for their photographs on the wall and continued to question the grid’s order and uniformity. They made changes in the placement, color, and size of images to challenge both the structure of the grid and, perhaps, the nature of the closet. They would maintain a gridded rectangular or square arrangement to their photo-pieces from this point onwards. If the earlier works (1970-1974) demonstrate a regulated appearance without strict reliance on the grid, the works after 1974 suggest more concentrated attention to the motif of the grid as the key element of their art. In addition, their subject matter became gradually more sexually suggestive and men other than themselves began to appear in their art. At the start of the 1970s, Gilbert and George had just begun a collaborative art career; by the end of the decade, they would be producing explicitly homoerotic art. In the next section of my essay, I want to examine the changes that occurred during these years in the use of the grid and the signifiers of gayness. I see the formal variations as linked with the subject changes, and I continue to insist on the comparison of grid and closet.

[16] The visual variations in the artist’s use of the grid involved the positioning of photographs on the wall from a separated, often haphazard grouping as in the nature and drinking pieces of the early 1970s to a presentation of individual framed pictures, hung in a gridded pattern, directly next to one another. In Red Morning Killing from 1977, sixteen rectangular frames produce a tight grid (figure 3). The physical arrangement of the pictures on the wall allowed the artists to experiment with compositional techniques.In this piece, for example, the abrupt shift from a crisp, straight-on view of one of the artists to a close-up shot of windows, to a downward shot of a reflecting pond and back again forces the viewer to hold several optical viewpoints in focus at once. The alternating and repeating images form a checkerboard pattern. The artists heightened this juxtaposition of images by their physical closeness — placing individually framed photographs directly adjacent to one another forced the viewer to read them as a unified composition and not as separate pictures. To further strengthen this effect, the artists occasionally allowed an image to bleed from one unit into the next as in Bad Thoughts No. 1 from 1975.12 Unlike the sixteen units of Red Morning Killingwhich depict individual, fragmented images, the four inner segments of Bad Thoughts No. 1are connected by the bodies that traverse them. Gilbert and George’s bodies fill two frames each, thus creating a large interior portion of each image. The four central rectangles read as one unit. The artists have manipulated the grid through the segmentation of their bodies into two equal frames and called attention to this change by repeating gridded windows around the edges of the work. Gilbert and George pushed this infiltration of the gridded units to an extreme in later works from the 1980s and 1990s, where the composition of the picture ignores the geometry of the grid; the male bodies are no longer confined to individual gridded compartments despite the prominent black grid that covers them.

[17] Yet another variation to the stabilizing and equalizing aspects of the grid came through Gilbert and George’s introduction of color. Although all sixteen segments of Red Morning Killing are tinted red, the artists alternated red rectangles with black and white ones in other works from this series. In Red Morning Murder, red sections produce a broken cross in the center of the work and draw attention to the squares containing the artists. In Red Morning Hate, the red units form the outer edges of the grid, and inRed Morning Reflection, red stains the four inner rectangles. The bright red photographs in these works do not produce clear sequential or narrative readings, but do interfere with the uniformity of the modular system and reassert the balance, tension, and variation of traditional compositions.

[18] Dead Boards No. 5, Red Morning Killing, and Bad Thoughts No. 1 all contain representations of gridded windows within rigidly gridded structures. The lines of the windows, abrupt shifts in viewpoint, and an occasional glimpse of distant scenery gives a dynamism to the pictures that heightens the viewer’s awareness of the artists trapped within, frozen into place. The grid functions both transparently, by allowing us to see through it to the images themselves and reflectively, by containing and defining the self-portraits of the artists. Reflection and transparency remind us of comparisons made between grid and window in reference to art of the late nineteenth century.13 In Gilbert and George’s pictures, the artists reflect each other. At the same time, both enact the doubleness of the closet, the need to be two people at once, to reflect society onto itself by assuming a traditional public role and hiding all evidence of difference.

[19] One way to hide difference was to adopt a public appearance that resembled other men. Since 1969 when they began to produce art together, Gilbert and George have worn the same kind of suits, which they call “responsibility suits,” and liken to uniforms.14 Like the grid found repeatedly in their art, these suits can be related to the notion of the closet. In their “first law of sculptors” published in 1970, they wrote, “Always be smartly dressed, well groomed relaxed friendly polite and in complete control.” This adage fits their public as well as their private lives. They have always been obsessed with manners, fastidious in their speech and precise in their actions. They have lived according to a strict routine, eating breakfast at the same workman’s cafe every day. And, according to reviews, they wore older versions of their suits when they worked in the studio, maintaining their rigid persona even in this private realm.15

[20] Gilbert and George have often spoken about their desire to be “tidy and clean and good” so as not to alienate their public. Indeed, when they painted large canvases for the first and only time in 1971, they mentioned their desire to be finished “and go and wash our hands.” The repression, almost denial, of the long, possibly messy processes in their dark room and studio indicated Gilbert and George’s rejection of the artist as manual laborer. Instead, they resembled dandified artists, like Andy Warhol and Marcel Duchamp, who relied on intellectual and mechanical modes of art-making and can be described as “hyperconformist” or “hypercorrect.” One journalist who visited the artists’ studio/home in 1972 suggested that the suits and obsessive manners made the two “tender young men [look] more alike, more young-gawkish and old-fashioned than they are.” More recently, a critic referred to them as “a sort of caricature of a certain sort of Englishman…very buttoned up.” By rejecting manual labor and adopting a fastidious appearance, they purposely linked themselves to the effete gay dandy stereotype popular in the 1960s and 1970s and portrayed in film and theater productions such as Harold Pinter’s “The Collection” (1961), Peter Shaffer’s “Black Comedy” (1965), or Mart Crowley’s “The Boys in the Band” (1968).16

[21] Gilbert and George do not fully embody the exaggerated or effeminate stereotype of the dandy, however, and instead epitomize control, conservatism, and a middle class mentality. They never cross-dressed (as both Warhol and Duchamp did), and their suits lack the polish and fashionability of a true aristocratic dandy. Indeed, many 1970s critics noticed that Gilbert and George’s suits were “off-the rack” and “ill-fitting” and that the artists’ poses seemed artificial or parodic.17 In fact, the artists claimed they liked their suits because “they are just some boring suits. Ordinary. Boring suits.” While a carefully tailored suit might link the men with an upper class, a slightly ill-fitting suit points to camp, masquerade, and role-playing.18 Mediating the role of the middle class man allowed Gilbert and George to distance themselves from their viewers. By adopting a respectable outer appearance, one that differentiated them from the hippies of the late 1960s, but also from the stereotype of the dandy, the artists embraced a certain middle-class, “inoffensive” public pose.

[22] Gilbert and George claimed their public appearance merely reflected how they looked and acted in private and was not, therefore, a discrete work of art or performance. Such a coherent, repeated presentation, however, (both in their public appearances and in all the photographs they took of themselves) suggests a conscious pose. In the repetition of this constructed identity, the artists played with signifiers of class and sexuality. Their suits linked them to a working middle class — businessmen and bankers. In her critical essay about the performativity of male artists’ self-presentation, Amelia Jones suggested that male artists after 1960 frequently wore

quintessentially middle-class, masculine clothing — that is, not the ‘creative’ variations on bourgeois dress common in the nineteenth century, nor the working-class garb taken up by artists from Cézanne to Pollock, but the everyday business suits or formal wear donned by middle-class men.19

Her discussion of French artist Yves Klein’s tuxedo during his 1960Anthropometries or American artists Chris Burden and Robert Morris’ conventional suits during their 1960s and 1970s performances serve as framework for her claim that such utilization of everyday bourgeois clothing acted as a kind of defiance for the artist. She noted, “within late capitalism’s culture of the simulacrum…artists’ deployments of the signifiers of middle-class stability read as parodies of the modernist conception of a stable, unified (and implicitly masculine) western subject, and, by extension, of the male artist genius.” Her description aptly fits Gilbert and George’s commonplace suits and the artificiality of their actions. They simultaneously mocked and embraced the conservatism of the suit-wearing businessman. Their public portrayal of themselves through interviews, performances, and multiple photographs act as parody of the male artist as genius.

[23] In turn, this constructed identity called into question traditional notions of gender. Sexuality, they seemed to be arguing, can be performed through clothing and gesture. It was an imposition from outside the self, an imitation or mimicry of societal standards. Gender represented a social practice, an activity with codes and signifiers.20 Re-enacting cultural norms in the privacy of the studio as well as in the public realm allowed the artists to find safety behind a uniform disguise; their unchanging appearance acted as a defense mechanism, a closeting device. When no identity is stable, and sexual identities make people uneasy, posing provides a means of constructing a seemingly whole image of the self, a self that is understood to be masculine and heterosexual.

[24] By representing function, durability, and convention Gilbert and George’s suits act as metaphors for both the grid and the closet. The clothing structures the artist’s visual appearance, making them resemble each other and any number of (heterosexual) men in contemporary society. Indeed, their constructed public appearance, their pose, is imitation or mimicry of something else, and, as Craig Owens has noted, “mimicry entails a certain splitting of the subject: the entire body detaches itself from itself, becomes a picture, a semblance.”21 The suits attempt to reconcile societal “grids” or norms of behavior and dress. Wearing similar suits and adopting similar speech and gestures, Gilbert and George become anonymous and interchangeable — equal units in the uniform grid of society; they are not unique but one of many, or two of many. This insistent duality seems to have been part of their strategy and early reviewers often ignored which artist was Gilbert and which was George. One critic wrote that “the names are interchangeable” and identified them incorrectly. Several others listed their names together, suggesting that one man spoke for the other, that their individual responses represented both of them.22 The artists encouraged this confusion by completing each others’ sentences during the interviews and thus becoming shadow images of each other — reflections or repetitions.

[25] In the final section of my essay, I want to discuss a pivotal 1977 series entitled The Dirty Words, in which Gilbert and George defied the grid’s uniform all-overness and also suggested a bold new interpretation of its confinement and limitations. These changes in the grid coincided with a shift in their subject matter from the earlier self-referential imagery (1970-1974) to the inclusion of people other than themselves (starting around 1977) to overtly sexual subjects (1980-1999). In other words, as they continued to break out of the grid’s confinement, they also seemed to be challenging the closet. The Dirty Words series combined large graffiti swear words on the top of gritty, urban scenes, anonymous Londoners, and self-portraits of the artists. This series contained the first photographs of people other than the artists; Gilbert and George intermingled their now-familiar studio self-portraits with pictures of total strangers. Critics have noted that the artists took an aggressive, socio-political stance in this series and have discussed the social rather than sexual aspects of the works. Certainly these images confronted destructive urban forces and revealed much about the changing face of working neighborhoods in London, but the blatant use of sexualized graffiti drawings and specifically gay slang in several of the works, such as “Bugger, Cock, Queer, and Prick Ass,” and the inclusion in at least one image of what appear to be male hustlers encourage a direct link with gay identity.

[26] Close-up views of the artists’faces peer out of two adjoining units at the bottom of the work entitled Fuck (figure 4). On top, the spray-painted swear word looms above the other pictures, setting a theme for the work, one capital letter filling each of four squares: F – U – C – K. Is fuck an expletive addressed to the viewer or a desire on the part of the artists? In the center of the work, just below the large swear word, two black and white photos placed side by side depict Parliament. Below them are two close-up shots of puddles, a dropped cigarette on the edge of one of them. In the lower portion of the work, the artists’ faces appear trapped, shot in close-up and literally framed by the strict rigidity of the grid. The placement of the enormous spray-painted swear word just above Parliament may indicate a political attitude on the part of the artists, a critique of government. These three rows of paired images represent three separate viewpoints, forcing the viewer to shift from close-up to distant.

[27] In red along each side of the composition, six frames in groups of three depict the same man in different positions. He poses provocatively near an open doorway, wearing flashy plaid pants and a blazer. In one frame he places his hand on his hip, pulling his jacket back to show off his waist and highlight his “gridded” pants. In another he grasps his hands together in front of him, looking around expectantly. Two other men enter the scene in different squares and their interaction with the protagonist suggests a narrative for the images. Indeed, the way they are grouped together in vertical strips and tinted red make the viewer consider them as a unified story. It is entirely possible that these pictures present the activities of a gay prostitute flirting with his customers.

[28] In another picture from The Dirty Words, the artists connected themselves with a pejorative label for gays — Q-U-E-E-R. Film critic Richard Dyer elaborated on the associations “queer” had with homosexuality and difference in the 1970s. His personal account of queerness as culture (art, music, theater) and therefore attractive to him may indicate why Gilbert and George chose to connect themselves to this word. The two artists stand alone and apart from one another in narrow, vertical spaces avoiding eye contact with each other and the viewer. Two male strangers in the center panels turn their heads downward, hiding their faces. Are they ashamed of Gilbert and George, of their own gay identities, or of their anti-gay stance? The work offers no clear answers. The word “QUEER” fills the entire top row of the work in large, capital letters. The artists’ passive presence below this label seems to implicate them in societal anger toward gays, an anger demonstrated in the shattered glass windows on either side of them and in the distant, impersonal view of the city below. The windows echo their earlier subject matter, but these are the first that show signs of violence. In an interview in 1974 Gilbert and George spoke of being followed home from a bar by skin-heads who smashed their windows.23 They spoke of the chaos of the flying glass, and while they laughed it off in the interview, the experience must have been frightening.

[29] With their inclusion in this picture, Gilbert and George play dual roles as both accomplices to the anger and targets of it. Their complicity in this hostility toward homosexuality is evidenced by their protective clothing that links them with a social norm (i.e. not gay). However, their isolated positions, blank, emotionless faces, and Gilbert’s clenched fist suggest personal experiences with anti-gay sentiment. Their doubled role epitomizes the complexity of the closet: it forces a gay man to abhor (or feign abhorrence of) his own nature. In Queer, the protective shield of the grid and closet has been literally broken, and the artists must face the public more openly (as they would do just three years later).

[30] By 1980, the artists exhibited openly homoerotic art. They photographed nude young men, close-ups of male genitals, and open mouths. At the same time, they continued to wear their conventional suits, to include their artificial, by now trade-mark self-portraits, and to install their works in strict grid arrangements. This adherence to the grid as the building block of their art and to their rigid persona as their “signature” points to the constructed nature of art and life. Gilbert and George have said that the grid represents the step-by-step evolution of life and that everything must be divided into segments — a week, a month, a building. Can the same argument be made about the closet? Could it, too, be the evolution of life, the hiding and exposure of secret identities? If the grid/closet represented societal repression of sexuality, especially of homosexuality, it also allowed the artists to explore and expose this sexuality precisely because it granted them a certain protection or distance from their viewers. This too became part of their identity. Both grid and closet were restrictive, but necessary constructs for Gilbert and George. Limitations required them to invent new means of self-expression and self-representation. They could be in or out of the closet, but they could not completely dismiss it because it continued to define their contrived public role. As Michel Foucault asked in The History of Sexuality, “Should it be said that one is always ‘inside’ power, there is no ‘escaping’ it, there is no absolute outside where it is concerned, because one is subject to the law in any case?”24 His essay about the transformation of sex into discourse and his ideas that repression forms the link between power, knowledge, and sexuality may clarify Gilbert and George’s stubborn reliance on the closet and grid in their art. They cannot let go of the grid (even when it no longer controls their compositions) nor their contrived public role (even after thirty years) because their power stems from various closets — from the response to societal repression of sexuality. Maybe that is the key to unlocking their early art. It was a response to repression, not a denial.

Notes

- The original ideas for this article date back to a seminar I took in the spring of 1995 at the University of Pennsylvania under the helpful guidance of Professors Christopher Reed and Christine Poggi. I am grateful for their encouragement. For examples of recent artworks by Gilbert and George as well as portraits and reviews, see their website at [www.gilbertandgeorge.co.uk] . For examples of how the artists have downplayed the significance of their relationship for their art, see Martin Gayford, “All We Want is Total Love,” Modern Painters (Winter 1995), p. 51. In this interview, Gilbert referred to reviews for The Naked Shit Pictures, 1994, saying: “We think it’s extraordinary that we managed to get away from this whole idea of gay artists, or gay couple. We hate all that stuff. Nobody said that.”

- For an example of misinformation found in 1970s articles about the artists, see Michael Moynihan, “Gilbert and George,” Studio(May 1970), p. 196. Moynihan cited George as being married to a kindergarten teacher with a sixteen month old child. It seems strange that this information never reappeared in the literature on the artists, as if it had been buried or forgotten. In 1972, another British critic asked the artists what would happen to the “natural rhythm” of their art should one of them marry. The critic ignored the nature of their relationship. Gilbert and George did not correct him, responding in an ambiguous manner: “‘I suppose it could happen,’ said George. ‘That would be that,’ grinned Gilbert.” Donald Zec, “The Odd Couple,”Studio (November 1972), p. 158.

- John Clum, Acting Gay: Male Homosexuality in Modern Drama(New York: Columbia University Press, 1992), p. 88. Clum continued, “Like any good performer, the closeted individual seeks approval by giving his audience what they want, but in the process he performs his shame at being homosexual.” See also Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, The Epistemology of the Closet (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), p. 68. For information about making visible the “invisibility” of homosexuality, see Jonathan Weinberg, Speaking for Vice: Homosexuality in the Art of Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, and the First American Avant-Garde(New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), p. 41. And also Richard Dyer, “Seen to be Believed: Some Problems in the Representation of Gay People as Typical,” Studies in Visual Communication (Spring 1983), p. 9. For Gilbert and George’s own reference to queer-bashing, see Gilbert & George, The Words of Gilbert & George, (London: Thames and Hudson, 1997), pp. 68-73.

- Krauss, “Grids,” October (Summer 1979), revised and reprinted in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths(Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1985), p. 9. My comparison of the grid to the closet introduces a method of analysis that may clarify other artists’ work from this period.

- Peter Plagens, “Gilbert and George: How English is it?”Moonlight Blues: An Artist’s Art Criticism (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1986), p. 267. For information on the screening effect of photography, see Joel Snyder, “Picturing Vision,” Critical Inquiry 6 (Spring 1980), p. 499-526.

- These photographs resemble portraits of the artists taken by Jacques and Jenny Gough-Cooper in 1972 at the artists’ home on Fournier Street and published in The Words of Gilbert and George, fig. 13.

- For examples of the Nature Photo-Pieces, 1971, see Carter Ratcliff, Gilbert and George: The Complete Pictures, 1971-1985, (Stuttgart: Dr. Cantz’sche Druckerei, 1986), pp. 34-37.

- Jeffrey Weeks, Coming Out: Homosexual Politics in Britain from the Nineteenth Century to the Present, (London: Quartet Books, 1977, revised 1990), p. 193, “In the end, the point was taken: the pubs did agree to serve. Within a few years the Chepstow was gladly allowing its premises to be used for gay meetings; and the space for gay people in London widened a little.”

- For a discussion of the distinction between gay desire and gay activism, see Leo Bersani, “Is the Rectum a Grave?” October(1987), p. 197-222. For Gilbert and George’s own words, see The Words of Gilbert and George, p. 71-73 and Ratcliff, Gilbert and George: The Complete Pictures, p. xxiv.

- Weeks, Coming Out, p. 194-195: quoting another writer, “Gay Days seem to me to provide a perfect fusion of self-liberation and external campaigning… We do our thing in the public parks. We show our gay pride to the world, and most importantly, to our gay sisters and brothers who have not yet joined us.” See also Andrew Hodges and David Hutter, With Downcast Gays: Aspects of Homosexual Self-Oppression(London: Pomegranate Press, 1974, 1977), p. 40, “we borrow little patches of territory–corners of public parks…”. About the anti-gay sentiment in their neighborhood in the 1970s, the artists said, “Gilbert: Yes, they kicked us in once. George: It was fun. It was the early days. This was in Finsbury Park, which is very tough.” in “Interview with Gordon Burn, 1974,”The Words of Gilbert and George, p. 71.

- George as quoted in Ratcliff, Gilbert and George, The Complete Pictures, p. xiii.

- For a reproduction of this image, see Ratcliff, Gilbert and George: The Complete Pictures, p. 79.

- For example, see Krauss, “Grids,” p. 16, “But if glass transmits, it also reflects. And so the window is experienced by the symbolist as a mirror as well–something that freezes and locks the self into the space of its own reduplicated being.”

- In 1971, Gilbert and George wrote, “As day breaks over us we rise into our vacuum. The cold morning light filters dustily through the window. We step into the responsibility suits of our Art.” Reprinted in The Words of Gilbert & George, p. 35. Until quite recently the artists had never appeared without their suits, either in public appearances or in their imagery (except for the Red Morning Series of 1977, discussed earlier in this article, in which the artists shed their suit jackets). Surprisingly, several series of images in the 1990s have depicted the artists naked and half clothed.

- For the artists’ first law of sculpture, see Gilbert and George, “A Magazine Sculpture,” Studio (May 1970), p. 218. For a description of their daily routine and studio habits, see Brenda Richardson,Gilbert and George(Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1984), p. 8 and p. 52.

- For the artists’ remarks about cleanliness, see “Interview with Martin Gayford,” in Eccher, Gilbert & George, p. 63; “Interview with Anne Seymour,” in The Words of Gilbert and George , p. 48; Ratcliff, Gilbert and George, p. xiv; and Andrew Wilson, “Gilbert and George,” Journal of Contemporary Art (winter 1993), p. 48. For the reference to “young-gawkish”, see Barbara Reise, “Presenting Gilbert and George, the Living Sculptures,” Art News(November 1971), p. 62-65. For the comment on “buttoned up” see Martin Gayford, “All We Want is Total Love,” p. 50-53. For information on the gay dandy stereotype of the period, see Weeks,Coming Out, p. 162; and Richard Dyer, “Stereotyping,” Gays and Film: Revised Edition (New York: Zoetrope, 1984), p. 32: “an over-concern with appearance, association with a ‘good taste’ that is just shading into decadence.”

- Robert Pincus-Witten mentioned the “badly cuffed and cut rack suits” in Arts Magazine (October 1976), p. 19. Richard Lorber wrote of the “studied dignity of their mannequin poses” in “Gilbert and George, Sonnabend Gallery,” Artforum (May 1978), p. 59; David Russell mentioned their “camp sentimentality” inArts Magazine (December 1970), p. 47; Dore Ashton called them “parodies of English gentlemen, with their neat suits, assuming the postures of mannequins,” Studio International (November 1971), p. 200. In a later interview, Gilbert mentioned that “in the beginning when we didn’t have money they were second hand suits.” In “Interview with Martin Gayford,” published in Gilbert and George(Paris: Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris, 1997), p. 72.

- For the comment about the boring suits, see “Interview with Gordon Burns, 1974” published for the first time in The Words of Gilbert and George, p. 68. George continued, “We like clothes so that we can just fling them on every day rather than to have to think a lot about it.” For information about the performative nature of the dandy stereotype, see John Miller, “The Weather is Here Wish You were Beautiful,” Artforum (May 1990), p. 156. Gilbert and George’s self-conscious presentation of self parallels the notion of gay camp. See Jack Babuscio, “Camp and the Gay Sensibility,” in Richard Dyer, Gays and Film, p. 40-57. John Clum more recently commented that “what has been called the ‘gay sensibility’ is actually a ‘closet sensibility,’ an awareness of performance because of the need to perform, and a mockery of the roles one is expected to perform.” Clum, Acting Gay, p. 88.

- Amelia Jones, “‘Clothes Make the Man’: The Male Artist as a Performative Function,” The Oxford Art Journal (1995), p. 27. That clothing contributes to a constructed identity is made clear by Kaja Silverman: “The pose also includes within itself the category of ‘costume,’ since it is something ‘worn’ or ‘assumed’ by the body, which, in turn, transforms other worn or assumed things into costumes. When included in the pose, even a sensible winter coat ceases to be a source of protection against the cold, and becomes part of the larger ‘display.'” in Silverman, The Threshold of the Visible World (New York: Routledge, 1996), p. 203. For later quotation from Jones, see “Clothes Make the Man,” p. 27.

- See especially Judith Butler, “Gender is not a noun, but neither is it a set of free-floating attributes, for we have seen that the substantive effect of gender is performatively produced and compelled by the regulatory practice of gender coherence.” Butler,Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1990), p. 25-26. See also, Harry Brod, “Masculinity as Masquerade,” in The Masculine Masquerade: Masculinity and Representation, eds. Andrew Perchuk and Helaine Posner (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1995), p. 16.

- Craig Owens, “Posing,” Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power, and Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), p. 212. Film historian Stella Bruzzi has noted that “Masculine attire, traditionally characterised by consistency, functionality and durability, is exemplified by the suit.” She continued, “blandly straightforward: the suited man is dependable, the dandy is not.” Bruzzi, Undressing Cinema: Clothing and Identity in the Movies (London: Routledge, 1997), p. 69.

- For examples of confusion in identification, see John Russell, “New Names in London: A to Z,” Art in America (September 1970), p. 97: “Gilbert is English, George is Italian (or the other way round).” See also Donald Zec “The Odd Couple,” p. 158; and “Interview with Anne Seymour, 1971,” The Words of Gilbert and George, p. 4. (Incidentally, Gilbert is the short one with dark hair, George is taller, blonde, and wears glasses.)

- For a reproduction of this picture, see Ratcliff, Gilbert and George: The Complete Pictures, p. 115. For Richard Dyer’s statement, see Dyer and Derek Cohen, “The Politics of Gay Culture,” in Gay Left Collective,Homosexuality, Power and Politics(London: Allison and Busby, 1980), p. 176-178. Interestingly, the term “queer” may not have had the same positive associations for American gay men at this time. George has noted that this work “aroused more hostility among the so-called gay community than anywhere else,” when it toured America in the late 1970s, adding “Now they’re all using the word ‘queer’. It was ’77 when we did it.” “Interview with Martin Gayford,” Eccher, Gilbert and George, p. 113. For the artists’ comments about the aggression against them, see “Interview with Gordon Burn,” The Words of Gilbert and George, p. 72: George stated: “Anyway, they just started throwing all these milk bottles through the window. It was shocking really.”

- Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality: An Introduction, (New York: Vintage Books, 1990), p. 95. (Original Paris: Gallimard, 1976).