By Reed Underwood

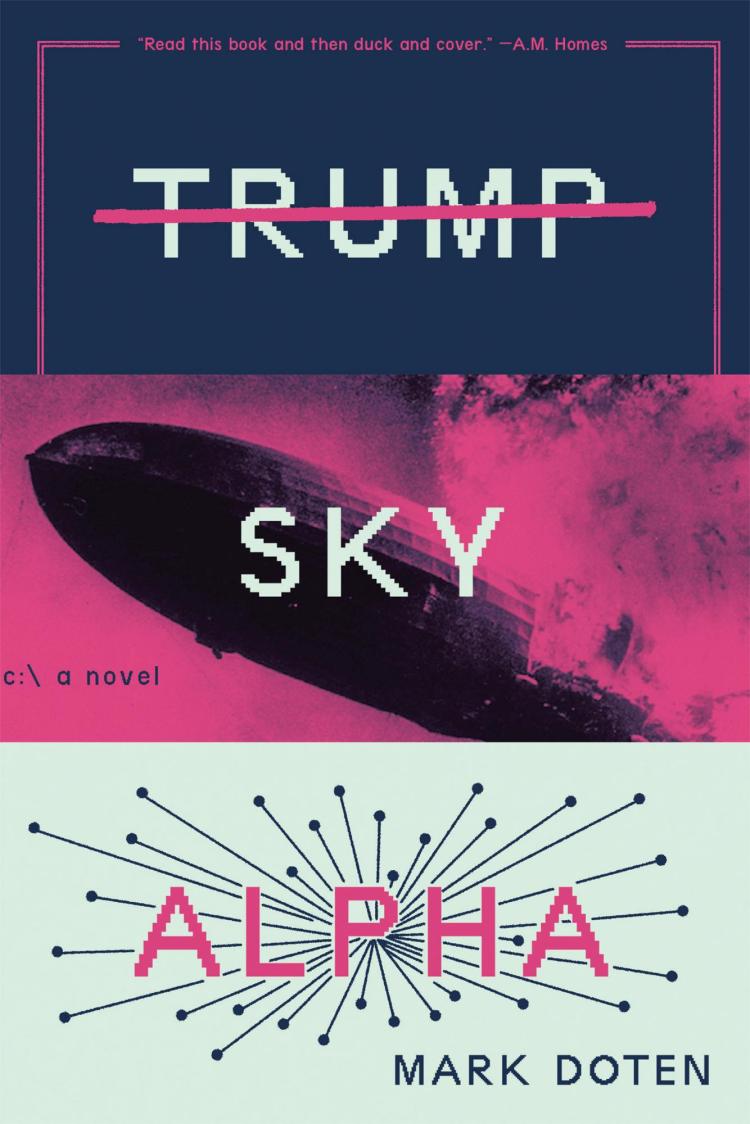

Mark Doten is the author of Trump Sky Alpha (available for purchase at Graywolf Press) and The Infernal. One of Granta’s 2017 Best of Young American Novelists, he is the executive literary fiction editor at Soho Press and teaches at Princeton University and Columbia University. He lives in Princeton, New Jersey.

Of all the things I’ve read lately, probably nothing got to me more than this: it’s the end of the world, Trump is popping off ICBMs, the response is incoming, and there, on the internet, someone posts the word “cute” 51 times in response to a “retweet of a twenty-one month-old tweet of an etonline.com story about a YouTube video headlined ‘Seeing this Puppy Scared of His Own Hiccups Will Change Your Life.’” In fact, at the end of the world, everyone is just posting. This is exactly the kind of corrosive irony and rending emotionality that’s running all around Mark Doten’s new book Trump Sky Alpha, along with a mysterious novel, a Filipino Charlie Chaplin, a journalist grieving her wife and daughter, a cyber-terrorist who may be responsible for nuclear apocalypse, and the president’s very own zeppelin. Trump himself gets a monologue that nails his addled speech patterns way better than Alec Baldwin ever has. But TSA goes beyond just a piece of political satire: it’s a inventive, powerfully written piece of art that just happens to use our present horror as its material.

I emailed with Mark in late January to ask him a few questions about the book. Trump Sky Alpha will be out from Graywolf Press on February 19th.

Reed Underwood: Your first book, The Infernal, was composed of a series of insane, circuitous monologues by various personages from the War on Terror, though none of them ever seemed quite themselves. Trump Sky Alpha seems to have a bit more of an objective stance. The main character is a journalist, there's sequences of third person description and documentary interpolation. What prompted this change in your approach?

Mark Doten: It’s true that the political figures in The Infernal are often wrenched quite a distance from their actual, historical selves. While the unhinged, impulsive, megalomaniac Trump I depict in Trump Sky Alpha is not all that far from the actual Trump—the dial on his character is turned up a bit, and there are fantastical elements—the world in Trump Sky functions in a more direct and realistic fashion than in my first book. I’ll leave it to others to say what effect the The Infernal’s strategies have, but I was very conscious this time around about doing something different. Part of the change was just that: do something different, challenge myself as a writer in new ways, have a narrower focus, a more legible plot, greater clarity about characters and events. But the main factor was the urgency I felt with this one: I wanted to write the book more quickly than the first, which took almost a decade. Here, my goal was to write swiftly, with heat, capture something about our moment, and get the book out in Trump’s first term.

RU: You've written about the War on Terror era Bush administration and now the Trump administration, too. What did you find different with writing about these two different packs of maniacs?

MD: People have forgotten just how bad the Bush administration was. Bush lied his way into a war that killed hundreds of thousands of people, perhaps a million or more. Of course, the actions of Trump are terrible and destructive in so many ways, from the ongoing tragedy at the border to shredding international relations to enacting devastating environmental policies. And the general rhetoric from Trump and those around him is corrosive and dangerous in new ways. But what I find interesting here is the less the differences between the administrations than the rehabilitation of Bush in the era of Trump. Bush was one of the worst presidents of all time, and the world was in significantly worse shape when he left office than when he was sworn in. People will be living with his mistakes for as long as there are people, and the fact that he and Michelle Obama pass notes or cough drops or whatever at public functions does not change this.

RU: It's become kind of commonplace to say that the president is beyond satire, that what's happened since the election is so absurd that not even a comic novelist could come up with it. And yet, you've written a very funny (but also very appalling) book about Trump and the world he's helping make manifest. What strategies did you use to make political irony great again?

MD: Thank you. For me the secret was capturing the odd, scattered textures of his speech and vocabulary, and hitching that to a scenario that couldn’t help but outstrip reality. Even if Trump does start a nuclear war, he won’t do so while piloting a fleet of zeppelins, as he does in my novel. Of course, the president’s way of speaking is so strange and off that you can never predict just what oddly broken thing he might say next, so in a sense he’s an impossible target and the reality will always elude any attempt at satire.

RU: The section of the book called "Internet Humor at the End of the World": let's just say it messed me up. As someone who was extremely online from mid-2015 through mid-2017, it was terrifying to see all these memes and memories regurgitated in an apocalyptic setting. How did you go about writing this section? Was all this stuff just rattling around in your brain? Did you do back research? What did the process of assembling it all look like?

MD: That was the idea that I started the book with: what would social media be like when the world was ending? And the answer I came to was: not so different from how it is now. People on Twitter would be making the same jokes and would be thirsty or combative or witty in much the same way people are every day. I hadn’t spent any real time on 4chan prior to researching the book, so that was an eye opener. But I’m fairly addicted to Twitter, so for the Twitter-based riffs, it was a question of paying attention and finding the types of tweets, the right memes and attitudes that I could collage into an extremely online portrait of the end of the world.

RU: On the issue of irony: is it good? I mean to say: it seems to me that there's a low-grade suspicion of irony as an aesthetic mode lately. Maybe I'm wrong about this, but it seems like, especially with art that has a political bent, a lot of folks prefer it played straight. And yet, to my mind, most of the best political art out there right now is snarky people on Twitter and on podcasts, and your books, too. But at the same time, the ironic mode is kind of a non-starter as far as pushing for real change. So I guess my question is, what is the relationship of irony and humor to material-political reality?

MD: That same suspicion was big after 9/11, too: is irony dead? But forms of that question have existed for I’m sure as long as literature has. Just in our relatively recent history, in the '70s, '80s, and '90s, realist writers were constantly dissing postmodernists and metafictive writing as bloodless and too ironic, and I’m sure you can find a quote or two from postmodernists calling the realists simpletons. I personally think you can have it both ways: if Trump Sky Alpha is working properly, it should have both moments of extreme irony and of genuine emotion and pathos.

I’m going to broaden your last question about material-political reality a bit, to how literature can shape real-world politics, whether ironic or not. That’s a question Trump Sky thematizes with the novel-within-the-novel, which does change the world within the novel, though not in the way the author intended. That’s a rare, outlier case, however. You can only occasionally trace policy changes or upended electoral outcomes or revolutionary acts directly back to a work of literature. But good literature and art (ironic or not) offers us new ways of seeing the world we live in, new points of view, and can, for instance, center stories from marginalized groups that many people might otherwise like to ignore. I think that cultural work is tremendously important. Most literary fiction has fewer readers than the most poorly rated television shows, but it has an outsize cultural effect and can shape the way we think about and perceive things. I know that great books have done that for me more often than any other cultural product. I hope it goes without saying that writers and readers should also be marching, canvassing, voting, in addition to buying or borrowing lots of books.

Reed Underwood is an MFA candidate in fiction at the University of Colorado Boulder. His work has been published at Killscreen and The Atlantic. He lives in Denver.