Power Switch

An “interstate for electrons” could revolutionize the American energy grid

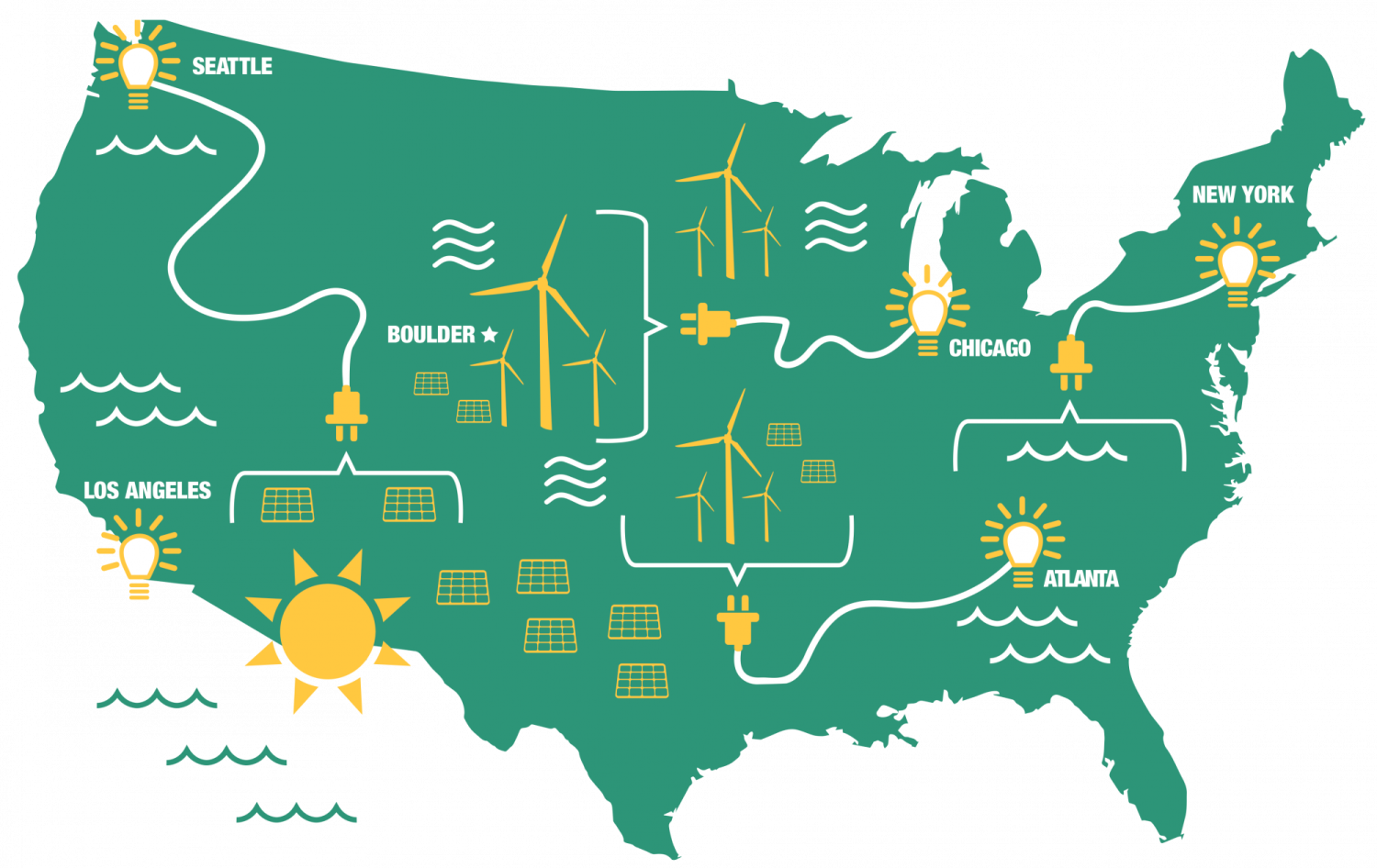

Could a breezy afternoon on Colorado’s eastern plains power downtown Chicago? Or sunlight from Phoenix electrify Seattle on a cloudy morning? What if wind and solar power could be made mobile, cheap and renewable? Oh, and help the U.S. cut its energy sector carbon emissions by up to 78 percent by the year 2030?

This seemingly futuristic vision of America’s energy grid is not just the stuff of science fiction, thanks to researchers at CU Boulder’s Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), who have modeled an “interstate for electrons” that would allow the electricity generated from renewable power sources in one area of the country to zip to another area as quickly and efficiently as autos on the highway.

Wind and solar power have long offered enormous environmental benefits compared to fossil fuels, but harnessing them on a national scale has proven challenging. The sun doesn’t shine everywhere all the time, nor does the wind blow consistently. Storing and transporting the power generated by turbines or solar panels requires expensive batteries, making it cost-prohibitive to expand wind and solar energy much beyond local use.

To tackle this problem, Christopher Clack, a CIRES physicist and mathematician, created a model that uses hour-by-hour meteorological data to identify where and when potential sun and wind energy are available over the course of a day. The sun can’t be everywhere, so the thinking goes, but it is always somewhere.

Once energy is harvested, a newly built nationwide high-voltage direct-current (HDVC) transmission grid would supplement current electrical grids and transport the power quickly to wherever it’s needed most.

“Hour by hour, the wind and solar power combined will generate the vast majority of necessary energy, and the rest is backed up by fossil fuels,” says Clack.

He also notes that what makes this system so unique is how predictive and dynamic it is in the face of ever-fickle weather. “The model relentlessly seeks the lowest-cost energy, whatever constraints are applied,” Clack explains. “And it always installs more renewable energy on the grid than exists today.”

Under this market exchange model, weather-driven renewable power could supply most of the country’s electricity at costs similar to today’s, even while slashing carbon emissions below 1990 levels.

The researchers have compared the idea to the interstate highway system, which transformed the U.S. economy in the 1950s by enabling fast, cheap transit across long distances.

“Eisenhower said that we needed interstate highways because if you manufacture in one part of the U.S., you want to be able to bring it elsewhere,” says Alexander “Sandy” MacDonald, the recently retired director of NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory. “It turns out that electricity is the same way.”

“The existing energy grid was built on a small scale, and that’s just a historical artifact,” says Clack. “What we really need in order to integrate these renewable sources cost-effectively is to build systems on the much larger scale of weather.”

Principal Investigators

Alexander MacDonald, Christopher Clack

Collaboration/Support

Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES); National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA); Earth System Research Laboratory (ESRL)