Louise E. Jefferson's work put marginalized peoples on the map.

In 2021, the University Libraries acquired a rare print of Jefferson’s 1944 illustrated map Indians of the USA. The acquisition is part of an ongoing initiative by the libraries to build more inclusive collections.

Louise E. Jefferson

A leader in the Harlem Renaissance, Jefferson’s artistic career was well known within Black communities but her work as a map-maker only recently gained attention according to a 2022 blog for the Library of Congress. Most active in the years 1935 to 1965, her work is now highly sought after and valued by collectors. Louise E. Jefferson was born in 1908 in Washington DC. She first learned to draw from her father Paul, who was an engraver for the United States Treasury. Her mother, Louise senior, was a musician and performing artist.

A leader in the Harlem Renaissance, Jefferson’s artistic career was well known within Black communities but her work as a map-maker only recently gained attention according to a 2022 blog for the Library of Congress. Most active in the years 1935 to 1965, her work is now highly sought after and valued by collectors. Louise E. Jefferson was born in 1908 in Washington DC. She first learned to draw from her father Paul, who was an engraver for the United States Treasury. Her mother, Louise senior, was a musician and performing artist.

Although her parents encouraged her to pursue a career in music, Jefferson studied fine arts at Hunter College and later at Columbia University.

Jefferson was socially and creatively active in the Harlem Renaissance during and after her years at college. She was a close friend of the poet, Langston Hughes, and a cofounder of the Harlem Artists Guild with sculptor Augusta Savage and others in 1935. The Guild sought to increase recognition of the contributions by Black artists and advocate for full participation in Federal Arts Projects funded by the Federal Works Progress Administration. With the Guild, Jefferson helped establish the Harlem Community Art Center in 1937 as a location for teaching and workshops.

Jefferson collaborated with many community organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the National Urban League while designing posters professionally for the Young Women’s Christian Association and the Friendship Press, the publishing branch of the National Council of Churches. In 1936, Jefferson illustrated a song book, We Sing America (viewable at the New York Public Library’s digital collections) which was reportedly banned by Georgia’s then-governor and subject to book burning.

By 1942 Jefferson became the Friendship Press’s artistic director. She was the first Black woman to hold a directorship position in the publishing industry, overseeing works on the health and welfare of children, culture, church missions and race relations.

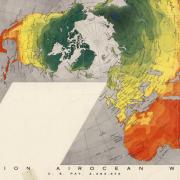

Jefferson’s maps Indians of the United States (1944), Uprooted People of the U.S.A. (1945), Africa: A Friendship Map (1945) and Americans of Negro Lineage (1946) were created during the time of her directorship and are viewable at the Library of Congress website.

Even after Jefferson’s retirement from the Friendship Press in 1960, she published Twentieth Century Americans of Negro Lineage – a copy is viewable via Portland State University.

She also embarked on multiple trips to Africa to research her book, The Decorative Arts of Africa, published in 1973.

Jefferson eventually settled down at her studio and home in Connecticut, where she enjoyed photography and her friends. She passed in 2002 at the age of 93 and gifted her estate to the Amistad Research Center in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Legacy of a ‘Counter-Mapper’

Jefferson is described as a ‘counter-mapper’ in a recent article for Cartographica. First coined by sociologist Nancy Peluso, counter-mapping is the practice of making marginalized peoples visible, both in terms of geographic spaces and also in terms of history. In her era, representing people of color or women in a historical document, like a map, was itself a statement of counter-mapping. Jefferson’s maps, however, go further than mere representation. Through illustrations and photography, they humanize their subjects, whether those figures are known people of color or nameless individuals performing the necessary, yet unacknowledged, work that built the nation.