How did you become interested in being an archivist? What was your path to where you are now?

How did you become interested in being an archivist? What was your path to where you are now?

I worked in the Archives while a graduate student in American History at CU. Like many history students and scholars, I had long been fascinated by primary historical sources: letters, minutes, diaries, journals, and other traditional sources. As I received more training in social history sources, I grew interested in non-traditional materials, as well: census lists, membership rosters, tax books, city directories, and so on. After I finished graduate school, I put my archival experience to work.

What are your principal duties as an archivist at CU Boulder?

Primarily, I field all of the emailed and mailed research questions, sent from students, scholars and the public from CU, and from academics and the public in the state, nationally and internationally. I connect them with finding aids, send them collection area lists, perform short-term research, and schedule all research appointments in the reading room. I also record all such traffic on our online statistical analysis program. In addition I work with the US Navy Japanese/Oriental Language School Archival Project, and our Labor collections. I am also the unofficial “memory” of the Archives, having served in the unit for a number of decades.

What challenges do you face as an archivist and how are you approaching them?

In the past, archives generally held to a passive role, awaiting visits and contacts by scholars. History students, faculty, and other seasoned researchers were well schooled in how to hunt down sources and their locations through time-honored analog methods. Today, however, students and younger faculty are accustomed to digital access, online discovery, and expect to search with their laptop rather than through boxes of papers. Archives must become an active advertiser and promoter of their holdings and activities. Research methods have also undergone a sea change, as well, going from pencil and paper note-taking and staff photocopying to free mobile phone and digital camera photography for notes. Policies have had to evolve quickly with the technology.

How do you evaluate whether certain materials have historical or enduring value, since the Archive’s space is limited?

Far more material has enduring historical value than can be acquired by our department. No archives can collect everything. What any archives can or will collect is generally defined by the overarching institutional collection development plan, put in place in collaboration with the administration, academic departments, and library leadership and bibliographers. If archivally important materials cannot be housed here, and I have been in a position to work with the donor, I have usually attempted to assist in locating other archival options, elsewhere, in keeping with the collection aims of other institutions.

How do you explain to others on campus what the archives are?

For the uninitiated, I use the TV show “CSI” metaphor, and say that we are the evidence locker for the court of history. Even when collections have been used for books and articles, as with police evidence, new methods, questions, or interests come along in the future that will require the use of these collections. I always have to tell them that: 1. everything is NOT scanned (only a very tiny bit); 2. even when scanned, archives cannot dispose of their paper collections. Retaining the evidence is key; and 3. there are many historical events that have been challenged or denied, despite voluminous available documentation. Maintaining the original records is one of our most central activities. We are in the memory business.

What are you most excited about in the Archives’ future or what hopes do you have for its further development?

Last year we began putting all of our finding aids on ArchivesSpace, an online platform which will make all of our collection finding aids immediately available on the worldwide web. This new development will have a similar effect that the introduction of email and the creation of a website had on us in the 1990s, multiplying our long distance patronage by many factors. We are already witnessing increased research visits. But once all of the finding aids are fully up, usage will go up steadily. We are also looking to developing a wide range of new collection development plans, and departmental policies, which will considerably modernize the department.

How did you first become interested in the Japanese Language School at CU Boulder?

When CPT Roger Pineau, WWII veteran and Navy Japanese Language Officer, began his research to write a book on that topic in the 1970s, Archives staff thought that the Navy or the National Archives held all of those records. But in the 1980s, as we discovered the Navy had not retained nor archived those records, we began to look internally for documents in the University collections: Student Registers, Regents Minutes, student publications, President’s Office Papers, and other holdings. But it was not until after Pineau and William Hudson donated their papers, and we began to receive research pressure from several scholars that we decided to create the US Navy Japanese/Oriental Language School Archival Project. We had always known that the school was at CU, so there was a CU connection. We also knew that the graduates who became language officers had contributed greatly to the war’s intelligence effort. What we had not known was how they humanized the treatment of Japanese POWs and Japanese civilians during the Occupation, served as informal diplomats and mediators between two proud and bellicose military societies, and came in the postwar period to dominate the academic, diplomatic and intelligence understanding of Japan and Asia.

I saw your name when my book club recently read Full Body Burden, and the author thanked you in the acknowledgments. How often do you get to work with authors who are researching for their books? Any favorites come to mind?

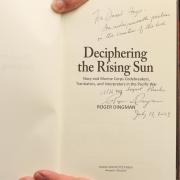

When archivists deal with decades of students, researchers, and scholars, the theses, dissertations, articles, and books often mention their names in the acknowledgements. I have been mentioned in books on hundreds of occasions: Robyn Muncy, Relentless Reformer: Josephine Roche and Progressivism in Twentieth-Century America; Irwin and Carole Slesnick, Kanji and Codes; Roger Dingman, Deciphering the Rising Sun; Robert Scott, Kenneth Boulding : a Voice Crying in the Wilderness; Steven Schulte, As Precious as Blood : the Western Slope in Colorado's Water Wars, 1900-1970; Joseph P. Bassi, A Scientific Peak: How Boulder became a World Center for Space and Atmospheric Science; Jerome A. Greene, Nez Perce Summer, 1877: the U.S. Army and the Nee-Me-Poo Crisis. But there are many more. I got to know these scholars quite well.

Other past projects you especially enjoyed?

From 2004 through 2015, I helped to send student assistants in the Archives to National Parks around the Country to perform grant-funded, ten-week, summer archival work. They went Yellowstone, Everglades, Grand Canyon, Florissant, Glacier, Glen Canyon, Yosemite, Redwoods, Sequoia, and World War II: Valor in the Pacific national parks and national monuments. In total, we sent 34 students to 49 task positions at ten parks, on which their travel, food, housing and salary was paid by US National Park Service grants. Not only did the students receive valuable professional and archival experience, which they brought back to their work in the Archives, they were able to enjoy ten weeks during the summer at a national park. These students underwent a transitional summer, or summers, and I was glad to have been part of those grants.

Thank you, David, for sharing with us your vast experience in the Archives and the impact the CU Boulder Archives have had on research in so many fields!

You can learn more about the archives in our series: 100 Stories for 100 Years from the Archives. This is story #91. We hope you will also join us as the University of Colorado Boulder Libraries celebrates the centennial anniversary of the Archives on June 6, 2018.

You can learn more about the archives in our series: 100 Stories for 100 Years from the Archives. This is story #91. We hope you will also join us as the University of Colorado Boulder Libraries celebrates the centennial anniversary of the Archives on June 6, 2018.