Two students tweak the ramp of a skateboarder in Energy Skate Park, sending her on a steep track that ends in a wild loop. They measure the energy of her motion as she goes.

The skate park may sound like an after-school hangout, but it's a cutting-edge computer simulation that -- along with animated cousins like Electric Field Hockey and John Travoltage -- is a boon to students and science teachers alike.

Now, new grants totaling $2.5 million from the National Science Foundation and the Dallas-based O'Donnell Foundation will allow the innovative University of Colorado at Boulder project to expand to a key area of need -- middle school science.

The PhET Interactive Simulations Project includes a total of 87 computer-based interactive science simulations. These extensively tested simulations are available for free on the Internet and are used in classrooms around the globe, contributing to CU-Boulder's leadership in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics, or STEM, education.

Founded in 2002 at CU-Boulder by Nobel laureate Carl Wieman, the team of scientists, software engineers and science educators use the latest results from education research to create high-quality simulations and associated classroom activities. The resources are designed to engage students and improve their learning of underlying concepts.

Over the past eight years, the PhET project has built on its original focus on physics (it originally was called the Physics Education Technology Project) and expanded its suite of simulations into chemistry, math, biology and earth science.

The free simulations currently are run over 15 million times per year with usage nearly doubling each year. The simulations have been translated into 50 languages and 34 percent of its users are from outside the United States.

Trish Loeblein, a physics and chemistry teacher at Evergreen High School in Colorado, says that in her 30 years of teaching she has seen many educational tools come and go. But she said PhET simulations bring unprecedented advantages to students, including the ability to visualize complex, and sometimes invisible, phenomena.

"Most young students do not have enough experience to visualize the process of physics happening, like I do in my mind's eye, after decades of study," said Loeblein. "The PhET simulations allow us to conduct experiments, with students at the helm, that we wouldn't otherwise be able to stage or model in the classroom."

When using the Energy Skate Park, for example, students can relocate a skateboarder to the moon, or Jupiter, to see the effects of gravity on motion, Loeblein said.

"Students also do not have to worry about breaking expensive lab equipment, so PhET facilitates a nonthreatening learning environment," she said. "The worst thing that can happen is to have to hit reset on the simulation."

The PhET project begins a major new effort this fall to bring these powerful educational tools to middle school classrooms. With the $2.5 million in new funding, the project will develop a suite of 35 simulations specifically designed for middle school physical science students.

"Research shows that middle school is a critical stage for many students, where they either get excited by science or turned off," said Kathy Perkins, director of the PhET project. "We believe bringing PhET simulations to middle school will help make science classes both more effective and more fun."

By watching middle school students use the simulations and examining the types of questions that are sparked by the simulations, the PhET team will gain insights into how to improve the simulations to engage students at this key age, Perkins said.

"We are so impressed with PhET's potential to transform how science is taught, and with what the project has accomplished at the high school and college level," said O'Donnell Foundation founder Peter O'Donnell, a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and a long-standing proponent of improving science education. "We think that bringing these learning tools to middle school students and teachers will improve math and science education in a measurable way."

To explore the PhET project and simulations visit phet.colorado.edu/.

-CU-

Physical sciences teacher Kathy Briggs of Southern Hills Middle School in Boulder looks on as sixth-grader Carmen Houck works through the "John Travoltage" program on the PhET Interactive Simulations Project website. (Photo by Patrick Campbell/University of Colorado)

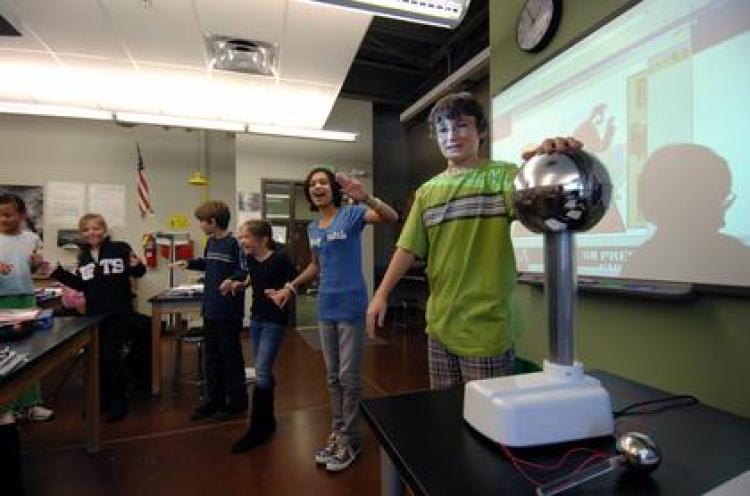

From right to left, sixth-graders Gerald Robinson, Carmen Houck, Gemma Truesdell, Wes Dolsen, Ellie Megerle and Livia Diener of Southern Hills Middle School in Boulder experiment with static electricity using a Van de Graaff generator and the "John Travoltage" PhET Interactive Simulation. (Photo by Patrick Campbell/University of Colorado)