Letter From the Editor

Hello Readers,

Welcome to the 2015 Summer/Fall issue of Timber Journal! We’re so happy to be sharing these amazing pieces.

This issue has come into being thanks to the hard work of the editorial staff, both old and new, and it seems appropriate to announce the changing of the guard. So, I’d like to thank last year’s Timber staff – Loie Merritt (Prose), Alexis Smith (Poetry), Kolby Harvey (Art), and Adrian Sobol (Managing Editor) – while welcoming this year’s. We are so lucky to have Erin Armstrong (Prose), Ansley Clark (Poetry), Loie Merritt (Art), James Ashby (Interview/Author Outreach Coordinator), and Sarah Thompson (Assistant Managing Editor) on our team. And huge, huge thanks to Ryan Chang, who has been our Social Media Coordinator for the last two years. We thank him for the continued Arrested Development jokes and truly hope it never ends.

We are dedicated to highlighting the best, innovative, compelling work by new and established authors. We hope you enjoy this issue and invite you to submit to the next!

Best,

Kathleen J. Woods

Managing Editor

Prose

A Wonder of the Goddamn World by Allison Gruber

At thirty-eight, I arrive in Arizona for the second time in my life.

The first, I was thirteen, with my parents; we drove for three days from Chicago to see the Grand Canyon, and I spent the trip feeling bored, unwilling to look out at what seemed to me nothing more than Biblically scorched earth and prehistoric holes.

At Grand Canyon National Park, I refused to leave the car, stubbornly turned pages in a tattered copy of Watership Down, until a series of escalating threats culminated with my father exhaling a frustrated burst of cigarette smoke through his nose, shouting, “For Christ’s sake! This is a wonder of the goddamn world.”

Even then, I knew wonder could not be commanded, but nevertheless emerged from the van long enough for my parents to snap a photograph of their eldest daughter in pink shorts looking petulant before a wonder of the goddamn world.

The second time I arrive in Arizona, by way of a turbulent six a.m. flight from Milwaukee, I am nervous and giddy. I listen to George Harrison, drink too much coffee, and take pictures on my phone of the pink earth below, uploading them to Facebook with the caption, “Breast Cancer Awareness Desert.”

People comment on the photo, “Where are you headed?”

But I do not reply.

***

Four years prior, halfway through twelve courses of chemotherapy, I decided I wanted a quieter life, spared of all unnecessary shocks and pain – including those wrought by romantic relationships. Cancer made it clear to me that lack of a lover was not lack of love, that there were worse ways to die than eating alone and choking.

Loneliness, after all, was just a branch on the tree of boredom that could be easily snapped off and repurposed – buy a dog, watch Netflix, get a tattoo.

In the meantime, I got a therapist so I could talk through the experience of having cancer at thirty-four, so I could sort out my thoughts about death, but mostly I ended up discussing women I had loved. How they all, ultimately, made me feel bled out whether murdered or cleansed.

And then, because it, too, is a symptom of cancer, I started a blog.

On my blog, I wrote about doctors, fellow cancer patients, and the side effects of treatments. My readership was limited to friends and family. And when I no longer had cancer, I stopped blogging.

Years after deleting the cancer blog, the Polar Vortex came to Wisconsin. It was so cold my dog refused to piss outdoors, so cold I swore into my coat while waiting for the bus —Fuck, fuck, fuck — and didn’t care if I seemed crazy, so cold idiots scalded themselves trying to demonstrate “flash freeze” by tossing pots of boiling water into the wind, transforming their desire for YouTube hits into emergency room bills.

Crazed with cabin fever, I started The Polar Vortex blog which was political, polemical, and written under a pseudonym. The blog was to alleviate boredom, to fill the hours when I was not teaching myself to cook elaborate meals I would ultimately throw out, when I was not watching a tragic documentary about justice denied, or grading tedious essays where students chronically confused “its” and “it’s.”

I usually posted a new entry once a week, and after several Twitter and Facebook shares, I developed an unexpectedly large readership, on my best days, garnering over fifteen hundred views.

Unlike my cancer blog, the Polar Vortex blog outlasted the winter that had begotten it, and at the start of summer, a friend who knew my “true identity,” asked if she might introduce me to a woman named Sarah, who was an avid reader of my site.

She’s a great writer, my friend said. Maybe you two could collaborate on stuff.

***

A month after the introduction to Sarah, I found myself in a canvas lawn chair, drinking wine from a plastic cup at an event called “Jazz in the Park,” which my colleagues had encouraged me, by way of friendly force, to attend arguing, The reason you hate Milwaukee is that you never do anything in Milwaukee.

Of course I did do things in Milwaukee: I taught, walked my dog, watched television and blogged. Sometimes, I rented a car and drove home to Chicago so I could tell friends and family, in person, how much I hated Milwaukee.

Jazz, like Milwaukee, bored me, so I drank wine and clandestinely texted Sarah.

Sarah did not bore me in the least. She was matter-of-fact interesting, one of those rare types who hadn’t spent much time considering how interesting she was. Without pretention, she’d offer anecdotes about that time she was on assignment in a Ugandan refugee camp or working security, illegally, at a housing project in Canada. Accustomed to people who crafted intrigue by aggressively drawing attention to their unorthodox philosophies, fanciful identities, sordid pasts, and fluency in esoteric subject matter, I’d sometimes laugh at Sarah’s nonchalance. Hell, the last woman I loved was a tri-lingual, bi-sexual, former sex worker who painted pictures of floating chairs and I knew all of this within the first half hour of meeting her.

Sarah lived seventeen hundred miles away, in a place I could not fathom, and after a week of incessant email exchanges, she suggested we talk on the phone. I hesitated, worried she’d find me much less clever, much more subdued than the voice in my blog posts, than the composer of lengthy, candid emails.

Whoever we are in prose, in a Facebook status, in an email is but a palimpsest of the true self, only the best parts.

Off the page, I was shy, moody, far less biting, and the phone call felt like an imminent unmasking.

I might be more boring than my persona, I warned her. She laughed and said she “doubted that.”

Despite my trepidation, our first phone call lasted over three hours.

Call again, if you’re ever bored, I said.

Or not bored, Sarah replied.

I laughed, Yes. Or not bored.

I had no intention of falling in love, but as our phone calls became more frequent, I soon found myself unable to eat; subsisting on black olives, coffee, and avocados I ate off the knife. On walks, I touched trees and flowers, anything that grew, my face lifting into a dumb smile. I let the worst ballads play themselves out on the car radio. Sometimes, I turned them up.

I was perpetually distracted.

I don’t want to be like this, I lamented, as though love was a deformity; my heart, John Merrick.

After my second cup of chardonnay, I turned to my colleague, Lynne.

I’ve met someone.

Knowing I volleyed steadily between school and home, Lynne cocked her head, Girl, please tell me it’s not someone from the internet.

I shrugged, said nothing, but wanted to clarify, “It is someone from the internet, but it’s not what you think.”

I was open about my disinterest in dating, in romance, had proudly declared “I have better things to do with my life,” and I didn’t want anyone to think I had some clandestine OkCupid profile. I was a woman of my word, and I wanted Lynne to know that Sarah wasn’t “someone from the internet” but an accident I had grown fond of: her clipped laughter, her sentence structure, her knowledge of subjects ranging from Kudzu to Catholicism.

I wanted to clarify that something even more unprecedented than cancer had happened, and I felt a sudden, indescribable sense of wonder that might be love.

My phone died mid-Jazz and I felt suffocated. I left the event early – “The dog needs to go out” — and once home, I frantically logged onto Facebook to message Sarah and explain that my battery died.

I’ve had wine, I typed.

Then, recklessly, I added, I might be falling in love with you.

Though I despise text-speak, I followed the admission with a “lol.”

The “lol” was an out. The confession that I’d drank wine was an escape. If I came across as foolish, if my feelings were unreciprocated, I could note the “lol,” the wine, as essential caveats.

***

You heard what happened to Dave, right? My stylist asked as he shampooed my hair.

I admitted that, no, I did not hear what happened to Dave.

He went to meet this guy he met online, like he flew all the way to Portland, and the guy never showed up at the airport.

I’d taken paid-time off work, asked my neighbor to get the mail, left my dog with a co-worker.

Normally a story like this would elicit an eye-roll, a smug, “Flying to meet someone from the internet is fraught with risk.” There were, after all, risks that were worth taking, like chemo, like moving out of state for a good job, and risks that were frivolous – like buying a plane ticket to visit someone you “met” in the lawless, anonymous wilds of the web.

But I had no judgment left now. Instead, my mouth went dry. This was not gossip, but a cautionary tale: I could be Dave.

Nevertheless, the following morning, I boarded my flight, assuring myself, If nothing else, it will make a great story. This was a bit of self-comfort ahead of the hurt, the way they say you shouldn’t wait for the pain to arrive before taking the pill.

On the plane, as we neared Phoenix, I studied the shadows cast by the clouds, feeling drowsy and proud of my own unpredictability. The entire situation was so completely out of character that I had shocked myself.

Prior to my departure, my best friend, Kristine, asked for Sarah’s address.

Why? I asked. So you can send me a letter? I won’t be gone that long.

In case you end up in a shallow grave, Kristine explained. I want details for Dateline NBC.

It was true that Sarah could be anyone, could be a stranger I had not anticipated, but I could be that stranger, too.

At the Sky Harbor baggage claim, I watched luggage clunk onto the carousel and a new panic filled my chest as I considered the limits of phone calls, email and photographs.

Sarah had only known me in fragments – what would she make of the pale, fearful whole? What would she make of this standard issue dyke, dressed more for a lecture than a romantic rendezvous, sweating through her blazer, dizzy with vulnerability?

I worried the back of my neck with a sweaty palm, until I saw her approaching in blue jeans and a fitted t-shirt. She was smaller and more attractive than I anticipated. She possessed an air of exoticism I had not noticed in the pictures she had shown me – her skin was a bit more olive, her eyes darker, a bit more upturned and bright.

I couldn’t speak.

She said, Come here, and pulled me in close as we waited, in partial silence, for my red suitcase to amble down the conveyer belt.

We had logged countless hours on the phone, we had texted incessantly through our workdays, mailed one another books, music, long letters written out on sheets of yellow legal paper, and she, once, sent me a bucketful of succulents in adobe pots.

On one hand, she was entirely familiar. There was no reason for me to tremble as I trembled, but for all the revelations that could not be communicated digitally or via USPS: the way she smelled slightly of sweet corn, the sturdiness of her knuckly hands, cool and roped with thick veins that made me think of blood draws, the way her teeth were so white they practically made me squint.

The cracks in my imagination had been filled in.

Are you disappointed? I asked.

She seemed shocked.

No. Why? Are you?

Of course not, I stammered.

And this was true. I was not disappointed; I was stupefied.

She had shown up. She materialized. She was real.

***

On the drive back to her apartment, we looked for a place where, like teenagers, we might park the car and fool around undetected.

The roads had Old Western names: Stagecoach Lane, Horse Thief Basin Road. Saguaros, stout and old, crucifixed the red earth.

I had forsaken my attempts to understand what was happening, and allowed the unlikelihood of the moment to engulf me: driving through the desert with a beautiful woman I met online.

For three days, we would hardly leave her bed. We would make love, talk, take occasional breaks to gulp water and eat spoonfuls of almond butter from the jar. Unaccustomed to being naked around anyone without a medical degree, it felt somewhat foreign to be seen in a way that was not diagnostic. But we joked about my missing nipple, Slightly used dyke. Missing a nipple. Probably won’t need it.

She touched my scars, the old and the new, as though browsing a book collection, and asked for the particulars of their origins.

This was when I was seven . . .

and this when I was fourteen . . .

and this when I was thirty-four . . .

The first morning, while she slept, I traced words I could not say onto her back. And when she awoke, I propped myself up on one elbow, and marveled, Where did you come from?

She smiled, and without missing a beat answered, I came from the internet.

But that first afternoon together, giddy on the very analog reality of one another, eager to take advantage of the disappeared distance, we parked the car behind some brush, the sort that men shoot at each other from in John Wayne movies, and I breathed in the vanilla lotion on her skin, a scent that lingered on my clothes so that, back in Milwaukee, when I opened my suitcase to unpack, a disarming gust of Sarah would breathe back at me.

As I clamored into the backseat, I was struck that though solid and strong, she was very small. My glasses fogged in the heat of the air and our breath, and I felt clumsy, oafish.

I don’t want to hurt you, I mumbled.

The blazer I wore on the flight, sweat damp, was heaped on the front seat, a discarded recent memory, someone I hardly know.

You won’t hurt me, Sarah assured, and I blindly accepted this because the slightest tap of logic against the surface of wonder can cause it to vanish, and because whether we acknowledged it or not, somewhere in the desert, in the heat that visibly warbled while we fumbled, muttered and laughed, was the actual truth: we could both hurt one another, terribly.

Despite this fact, or in honor of it, she reached for me and I reached back.

***

Back at Sky Harbor, I step into the TSA line, softly sobbing, and hand my driver’s license to a security agent.

My wallet was stolen by a student while I was in chemo, and my replacement license shows a sick, pissed off version of myself: “Hair Color: BLD.” The agent flicks her eyes at the picture, at me – she likely thinks I’m crying because of cancer. She smiles sympathetically, calls me “honey” as she hands me back my identification.

I feel foolish for crying in public, but I am ushered quickly and politely through the security lines.

I gather myself together enough to purchase an overpriced chocolate milk shake at the burger chain near my gate. I text a picture of the shake to Sarah, This is what misery looks like right now.

Once seated on the plane, I begin to cry again. It’s futile to disguise my tears as sudden allergies, as “something in my eye.” I cannot keep brushing them away; they just keep falling. The large man next to me wears a Green Bay Packer’s hoodie, reminding me of where I’m headed, where I do not want to be. He plays Solitare on his iPad, and doesn’t seem bothered by the weeping dyke. I fantasize that maybe the plane won’t be able to take off, that no plane will ever be able to take off again and I’ll have to stay in Arizona. I want to be stuck.

The following morning, quite under-slept, I’ll teach my Composition course. I’ll stand in a classroom in Milwaukee in front of seventeen students, who will not know their instructor’s whole life has changed. I will lead a discussion on Didion’s “Goodbye to All That.” I will say nothing about love or about Sarah even though love and Sarah occupy the whole of my mind. Midway through a tiresome thought about rhetoric, one I’ve had and stated countless times, I’ll notice that red rock dust faintly marbles my black boots, evidence from the walk we took in Sedona on the way back to the airport, when she took my hand and pointed to a field of small yellow flowers and called them “Allisons.”

I’ll notice the rust colored remnants of astonishment and lose all my familiar words.

Allison Gruber is an essayist and the author You’re Not Edith (George Braziller, 2015), which received praise from Booklist, Publishers Weekly, and Lambda Literary, among others. Her work has appeared most recently in The Hairpin, The Huffington Post, The Literary Review, and in the anthology, Windy City Queer. Her essay “A Music in the Head” received a notable mention in Best American Essays 2015. A Chicago native, she presently teaches literature and creative writing in Flagstaff, Arizona where she lives with her wife.

Weathervane by Thirii Myo Kyaw Myint

The boy died in the fall. He went to the island with a shotgun by himself, for himself, the shotgun. He didn’t tell anyone he had left.

Where the boy went it was cold. The woods were wet and the bark of trees black like the way the boy remembered the city.

You told me this story about the boy. You said he had lived in a boarding house in the city: water pump in the yard and no heat until mid-winter. Curtains stapled to the windows. Co-ops like that swelled on the outskirts: in old barns, mills by dead rivers, small rail stations where the tracks ran nowhere.

I say the boy died in the fall because no one saw him again. His letters kept coming for months after. Magnolias bloomed, daylight stretched into the last hour of evening, and still the boy went on about the cold, the dark, the trees closing all around him.

You tell me this story of the boy because it is spring and I am thinking of our child. The boy isn’t dead, but our child is in his stead. You tell me a story of a dead boy because is it sadder than our story, because the boy is sadder than us.

That fall on the island, leaves fell from trees by the fistful and ice closed over the ground.

The boy sent letters to everyone he knew. He wrote of fish who slept in frozen sand and how he walked all around the island in winter, trespassing on private beaches. He wrote of bluffs crumbling along the water, trees hanging on edge. Around the island nine times, the boy went, and into the woods.

What is your favorite kind of earth? he wrote, What kind of heart are you?

You copy his best lines into your novel, working in our fire hazard of a basement, with branches taped to the ceiling and the bedframe in the stairway. We sit on the mattress and you are writing of stalactites and sea monsters, and driftwood white like bones. I am reading over your shoulder. The sitar is a sweet and painful needle in my eye.

It is spring in the city and there is rain in the gutters, rain in the eaves, rain in the trees. We stand at the threshold of our building, where we’ve often stood before, where we stood one night under the portico and you asked if I could hear it, the highway.

It sounds like the ocean, you had said.

The trees made watery shadows that night on the wall of a neighboring building. The highway lay far away.

I can hear it, I had said, and though you were the one holding the door, I could distinctly feel its weight.

We stand there now, under the portico again. It rains.

The boy dies and his death is like a heavy door that you hold open for me to step through. His death like all the things that happened to us, and like nothing happened at all.

In the city where we live, the city where I was born, no one dies. What I mean is, no one really lives. I will go over to my grandmother’s house sometimes and my parents will be younger than I ever remembered. My sister will be glutted with children. Everyone will be jogging around the lake, rollerblading, riding their bikes, walking their dogs, and the evening will be so healthful and good and swaying so gently in the wind that I want only to bite off my hand, and throw it at the canopy of some passing stroller.

You won’t come out of our basement sometimes, and I don’t blame you.

The city is all neat blocks and numbered streets. Yellow brick fire station. The high school like a monolith.

As the snow banks were melting on the city streets, there appeared a darkness in the boy’s letters. Grotesque shapes that meant nothing or too much. The boy wrote that he was afraid to stop praying. He said he wasn’t sure what would happen, if angels would descend from the sky wielding swords.

And if a boy has prayed every day of his life, if he has kept the strictest precepts, indeed, what terrible things would happen if he stopped: either to him, or the universe.

The darkness extended in his letters, dark like the universe choking on its surfeit of creation, like the terror of a boy who had stopped praying, or a boy who had stopped to pray. Either way, they foretold the end of something, his letters; and because he was just a boy, and he was alone and unwell, it was the end of his life.

In every story someone dies. The boy is dead and the woods are heavy with the weight of his body hanging from the trees. His body, like a weathervane spinning where the wind blows.

I thought he shot himself, I say.

Same thing, you say.

In the novel you are writing, we are driving through the night, except you are not yourself, and I am the one who is dead. In your novel, there are precipices, and docks rotting by the water, and bridges drawn up to the sky. There are streets that thicken and change names and cross rivers and lie black and glossy in the winter, but in the summer are mirages. There is and isn’t some kind of constellation in the sky. The moon, or the many moons you’ve made, rise and set as they please, float through the wide and generous streets.

It is always night and you are always alone. You never run out of gas, you never feel hungry or thirsty or tired, and the sun never rises.

___

Thirii Myo Kyaw Myint is a Creative Writing PhD candidate at the University of Denver. She received her MFA in Prose from the University of Notre Dame and has been awarded residencies and scholarships from Hedgebrook, Tin House, and Summer Literary Seminars. Her work has appeared in Caketrain, Sleepingfish, The Kenyon Review Online, and has been translated into and published in Burmese and Lithuanian.

Marcel Broodthaers by Will Arbery

for Lucia Simek

When I was twelve, I interviewed to be in an advanced French class, very selective. I got in. I was on my way. All of Brussels bloomed. Then, after twenty years as a poet, and no one knowing my name, I sat stiff and weird in the corner of my room and came up with a joke. What if I could sell something and succeed in life? That’s the joke. I’m not good at anything, and I’m forty years old. I asked myself what art is. I looked at what was art. I looked at what wasn’t art. My quest was insincere. The only fact I found was: objects. I had forgotten that things were things. There are stools and eyes and hands and books and ink and desks. And there are shells, for eggs and mussels. There is furniture, clothing, garden tools, household gadgets, and there is art. There can be no interviews for the right to mine the human heart. I live in Berlin. Soon I’m going to live in London. Ha! I write in the rain, in the rain, until my words become painting, a joint work by the rain and my stubborn insincerity. I will attack antidotes. This is productive confusion. That’s the point. This is a critique of representation. That’s the comma. This is an invasion icebox. This is achieved contradiction. Children are not allowed in the museum. I’m not allowed to think so much. I’m not allowed to care so much. This block of text will split apart. I love so many people, and that’s something else. Let me in (or out).

––

Will Arbery is a writer and filmmaker. His work has been published by Better: Culture and Lit, decomP,Word Riot, Neutrons Protons, The Awl, D Magazine, and more. Last year, he was one of the winners of the Samuel French OOB Festival with his play The Logic. Next year, he’s part of the Kendeda finalist group at the Alliance Theater. He was a 2014 Theater Masters MFA fellow, and he’s enjoyed experiences with Dixon Place, Echo Theater Company, Road Theater Company, Calliope Theater Company, iDiOM Theater, Chicago Dramatists, and more. This fall, he’ll be directing Sofya Weitz’s LADY through The Araca Project, and making his short film Your Resources through a grant from Northwestern.

Two Flash Fictions by Alan Ziegler

The Realist's Weather Report

The sun is always out; the moon is always full.

Confrontation

I stand in front of my own door and push the bell repeatedly with one hand while banging with the other. Laughing as I push faster and bang harder. Open up! I yell. Open up, damnit! I know you’re out here!

—

Alan Ziegler’s books include Love At First Sight: An Alan Ziegler Reader; The Swan Song of Vaudeville: Tales and Takes (with an introduction by Richard Howard); The Green Grass of Flatbush (winner of the Word Beat Fiction Book Award, selected by George Plimpton); So Much To Do (poems); The Writing Workshop, Volumes I and II; and The Writing Workshop Note Book. He is the editor of Short: An International Anthology of 500 Years of Short-Short Stories, Prose Poems, Brief Essays, and Other Short Prose Forms (Persea Books). His work has appeared in such places as The New Yorker, The Paris Review, and Tin House. He is Professor of Writing at Columbia University’s School of the Arts, where he has received the Presidential Award for Outstanding Teaching and was chair of the Writing Program. He is currently at work on Based on a True Life: A Memoir in Flashes.

The Spaces Between Teeth by Nat Baldwin

We used to swim and float in the water of the lake. We would watch the sun watch us until our eyes blurred blind. Sometimes the sun is so hot there is no way to move. We watch them lifted from the mud one by one by one. Rocks stick to the skin of faces and do not come loose. We count twelve bodies before we stop to closely watch the boy. The boy’s mouth is the one mouth they find does not close.

*

The only sound is the sound of the sun burning the lake. There is no telling how long the bodies have been here. They are wrapped tight in wire and cloth, facedown and stiff. They do not uncover the bodies before reaching into mouths. They count the missing teeth and then fill the buckets up. They brush clumps of dirt from the skin on the faces. The dirt clouds the air and rises up to the sun. The faces do not look like faces we have seen before now.

*

With a hammer in their hands they tap the teeth in the mouths. The boy whose mouth does not close does not have teeth. We cannot see the movements of their hands in his mouth. They surround the boy’s body all dressed in black or white. They look like clouds of bodies themselves while working on the boy.

*

It’s been twelve days since the bodies have risen from the mud. The bodies float as if the mud were water of a lake. There is only the dark of the night and the sun’s heat. Cloth still covers the bodies and the men do not stop working. They are busy with the wires, they are busy with the faces. We want to move closer to see the details of the hands. They only stop to sleep at night but do not sleep much. There is only one that stays awake to keep watch. He paces back and forth and holds the hammer ready to hit. When birds fly on a face he swings the hammer just right.

*

They arrange the bodies in the mud at the top of the ditch. They grab the bodies by the ankles and lift them from the mud. It takes three of them to lift while only one holds the hammer. The others wait at the bottom of the ditch in the dirt. They make sure the skin does not scrape or peel or scratch. When a mistake is made they take a hammer to the mouth. They do not run or hide to avoid getting hit with the hammer. They spit broken bits of teeth into piles in the buckets.

*

We are wrapped in wire and cloth and stuck facedown in mud. They spin us in circles and untangle the wire from the cloth. They hold hammers to our mouths and scrape the spaces between teeth. We are blinded by the sun and hear nothing but the dirt. The dirt is being dug next to our bodies, our heads, faces. They unwrap the cloth and our bodies ache and bulge and leak. Birds land on our faces and dig at our eyes, our mouths. We choke on their feathers when they get caught in our throats. Our throats are dry and filled with dirt and heat and rocks. They brush the dirt caked to cloth and clouds fill the air. After twelve years at the bottom of the lake we are seen. We can’t hear the hammer swing but feel it in our teeth.

*

The sun burns us awake and we did not know we slept. We hear the breath from a mouth and the sink of mud. Our whole bodies ache as we step into the ditch. It’s been almost twelve months since we’ve moved from the mud. There are scattered feathers and bones and wires and cloth and skin. The bodies dry in the heat of the sun with eyes open. We watch them watch the sun, the sun watching them back. They are dressed in black or white or in nothing at all. They do not move when kicked to the face with boots. We try to speak but words clip and catch in our throats. We find a hole of dead birds and buckets filled with teeth. The parts of dirt that were not yet mud turns to mud. We have no choice but to grab a body for ourselves.

___

Nat Baldwin is a writer and musician living in Maine. His fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in Sleepingfish, Alice Blue, and Deluge. He has released several solo albums, and plays bass in Dirty Projectors. He is currently pursuing a BA in English at the University of Southern Maine.

Poetry

The Plurality of Each Each by Kevin McLellan

water understands and follows

which is not to say it respects

the outside. this is where

at least one of me gets lost.

in other words won’t accept again

instead of drinking

a glass of milk (measurement

irrelevant) and not wondering

the outcomes. although today

one of me the one who decided

the one who decided wanders.

for this I am grateful.

—

Kevin McLellan is the author of Tributary (Barrow Street) and the chapbook Round Trip (Seven Kitchens), a collaborative serious with numerous women poets. His chapbook Shoes on a wire (Split Oak Press) and the book arts project (Small Po[r]tions) are forthcoming. Kevin won the 2015 Third Coast Poetry Prize, and has recent or forthcoming poems in journals including: American Letters & Commentary, Colorado Review, Crazyhorse, Kenyon Review, West Branch, Western Humanities Review, Witness, and numerous others. He lives in Cambridge MA.

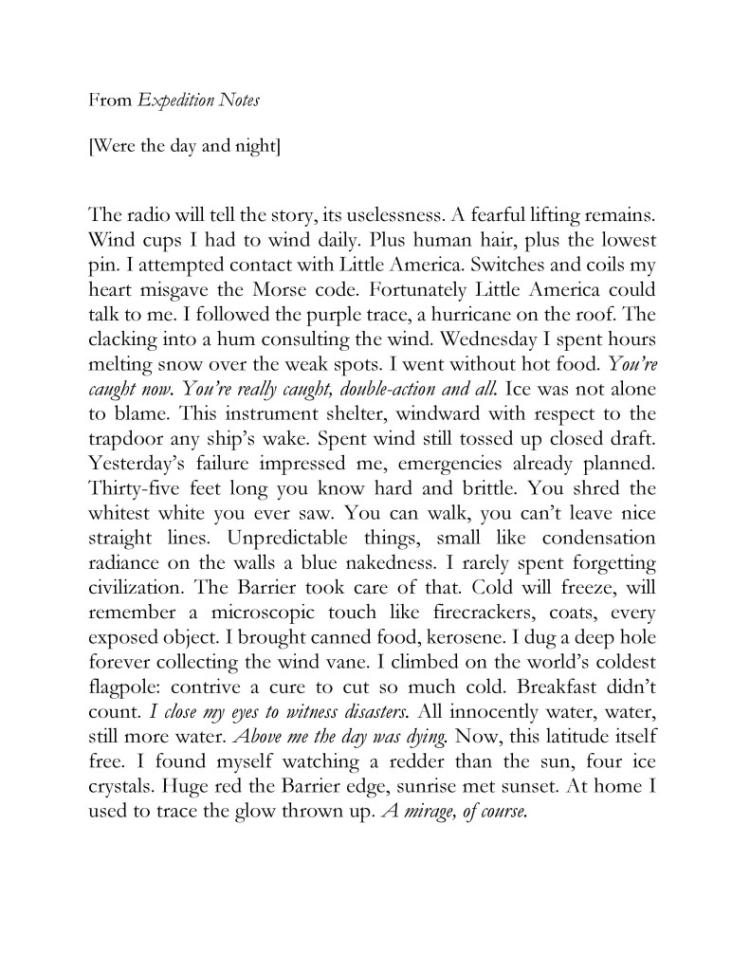

“Were the day and night” by Carrie Bennett

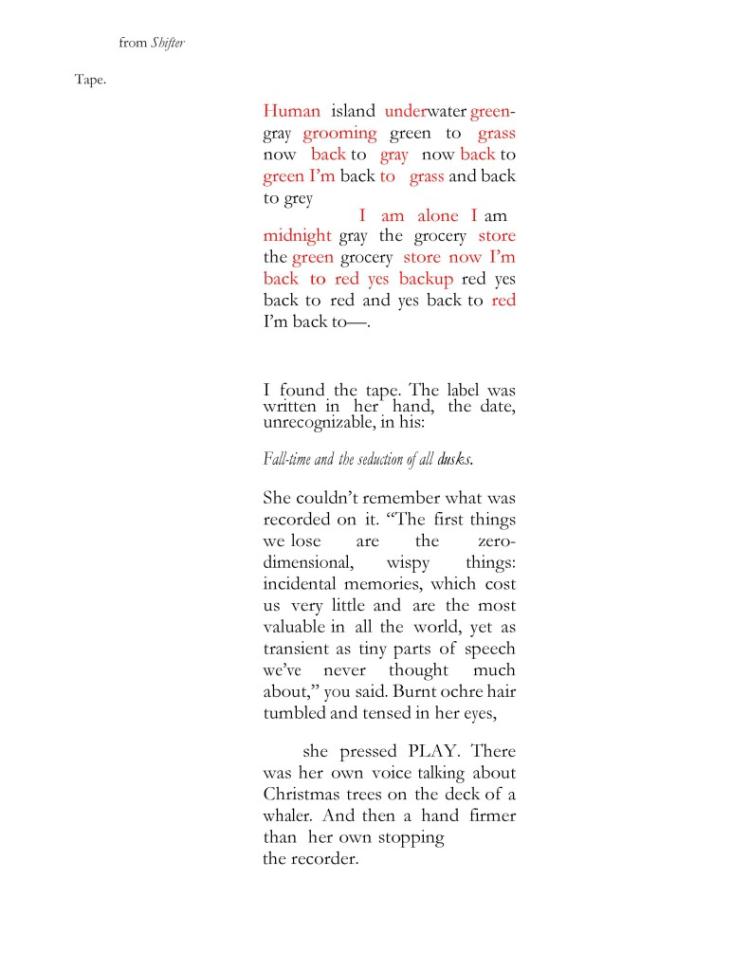

Four Poems by Marco Maisto

—

Marco Maisto’s chapbook The Loneliness of the Middle-Distance Transmissions Aggregator was a finalist in YesYes Books 2015 Vinyl 45s contest, and his poem of the same name won the Bayou Magazine’s Kay Murphy prize. Marco co-edited the Poetry Comix & Animation folio in Drunken Boat #20. His hybrid art and poetry can now or soon be found in Spry, Fjords, Drunken Boat, Rhino (Editor’s Prize Finalist), 3Elements, Heavy Feather Review, Tupelo Quarterly and Small Po[r]tions. He attended the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. He lives in NYC with his wife, the painter Margaret Galey. Read fun chunks of language @MarcoMaisto and contact him through marcomaisto.com.

Interviews

Interview With Allison Gruber by Loie Merritt

Allison, I want to thank you for taking the time to speak with me on the eve of the publication of your first collection. You must be very excited. Please bear with me, as there’s just so much I’d like to pick your brain about.

• As a writer of predominantly creative non-fiction, this burgeoning genre that so many Americans seem to devour, how do you balance your most intimate experiences, your most secret pleasures and traumas, with the necessity of telling the capital T – Truth?

I think this is where knowing the purpose of a piece of writing comes into play. Usually, before I even set about writing an essay, I have a gut-level sense of where I want it to go, what themes or issues or ideas I want to explore. In this way, I can choose what particulars from my own life are germane, that will facilitate what I have in mind. I mean, if I’m writing to shock or scandalize or whatever, then I’m just an exhibitionist – but I’m not doing that. When I tell the truth, when I’m candid, I’m doing this to serve the purpose of the piece.

I’d like to think there are things about my life that I’d never reveal on the page, but nothing’s really off limits when you greedily mine your own experience, as I do. For example, I have avoided, in much of my work, writing about sex – save for passing mentions of its existence. I’ve done this, in part, because I’m terrible at “sex writing” and because I believe talking about sexual experience, my own, is just too damn personal. Often, it seems, in memoir when people write about their sex lives, it seems to serve a singular purpose: to shock. And, again, I’m not interested in shock for shocks sake.

However, I’m currently working on a new piece where I’m investigating what it means to be intimate when your body has been changed by disease, so I’m finding that in the context of this particular essay, I need to write a bit about my sex life. So, yeah, if the piece warrants revealing something that makes me uncomfortable, something I’m inclined to keep secret, I’m willing to expose it. Candor is important, particularly if you care about whether or not the reader trusts you.

• Can you expand a little bit about your process? Where do you start? How do you know when you’ve finished a piece? I’d also love to hear, in particular but not exclusively, about the new collection, You’re Not Edith (George Braziller 2015). What excites you most about a project like this one?

Typically, I start by telling a story that I think is just a damn good story, and one that I, intuitively, suspect is pregnant with larger meaning. But in that first draft, I’m not even necessarily thinking about the nuances – I’m just following my gut. Once I have the story down, just the bones, I go back and re-type – the whole thing, start to finish. This allows me to slow down and dig deeper into moments from the story that, I feel, possess meaning and significance that are bigger than the experience itself. Re-typing the whole thing also allows me to finesse the language, consider the cadence, consider the work holistically in order to make choices about what stays, and what goes. Sometimes you think you know what a story, an essay, is trying to do but once you’ve cobbled together that first draft, you realize it’s about something else altogether.

It’s hard to ever really know when a piece is truly finished, but for me, a good indicator is usually the sense that there’s nothing superfluous left, and all the moments are working together in a harmony that I could succinctly articulate, in a harmony that makes sense to me, and will, ideally, make sense to the reader.

You’re Not Edith was really interesting because the first half was written when I was living in Chicago, leading a totally different life than the one I ended up living when I moved to Milwaukee and got sick. I really got a thrill out of discovering threads that connected two seemingly disparate parts of my life – before cancer, after cancer. As a writer, I’m really, really interested in how experiences overlap – it’s a sort of intellectual game, trying to figure out how, say, an overheard conversation on the bus might relate to the experience of attending a funeral. So working on You’re Not Edith was great, because I could think about interrelatedness not just within the confines of a single essay, but within the span of an entire collection.

• You work in academia, as do so many of our staff and readers, how has the “job” influenced your writing? Do you ever catch yourself considering the presence of your academic community as you write out the more personal aspects of your essays? I also wonder, how do your loved ones feel about the collection? To what degree does this matter to your process and/or finished work?

As a personal essayist, I’ve often think of my life as a text. I read my experiences in much the same way I’d read fiction or poetry. As an educator, a teacher of writing and literature, this comes somewhat naturally to me. I seek meaning and symbolism in the work of, say, Dickinson or Woolf – so why not apply that same search to my own life? In this regard, my profession and creative process feel very much intertwined. When I’m writing about my own life, I’m employing many of the same techniques I do when analyzing literature.

Right now, I’m teaching high school – which is a total trip, and not something I expected to be doing. However, when I was developing You’re Not Edith, I was working in academia. And though I love academia, I am not an academic. I have academic inclinations and interests, but really, I’m something of an outsider within that world – as are all writers and artists, I think, who find themselves employed by colleges and universities.

So in terms of academic audience, while working on You’re Not Edith, I didn’t think so much about my colleagues, but I definitely thought some about my students. I try, as an educator, to keep details of my personal life away from students, from the classroom, and many of the stories in You’re Not Edith expose my private life. I did wonder a lot about how students would view me if they read the essays and were confronted with, you know, their instructor’s sex life or private struggles with things like mental health. But ultimately, it didn’t influence any of my choices about what to include or not include in the work. The only time I really am given pause by the thought of a particular audience – be it my students, my friends, my family – is if I’m at risk of breaching some kind of confidence or exposing someone in a way that would be hurtful.

• You share, with such bravery, your relationships with lovers, family, and friends in unflinching honesty blended with your own particular variant of dark humor. How do you balance the use of humor with compassion in these depictions of yourself and the community that surrounds you?

My thinking is that if you’re going to use your own life for material, then you have to be frank, you have to be candid, you have to tell the truth. That’s what makes for compelling reading. I feel like if you want to write personal essays, you need to be willing to unmask yourself, to expose yourself in a way that might make you, the writer, a little uneasy. Really, for me, that sense of unease while I’m writing is a sign that I’m doing something right, that I’m on to something good.

And I write about people, things, events that I truly care about. This makes the compassion come easily. There’s this cliché, this “joke” about “not pissing off writers” because the writer will, like, put you in their work and make you look awful or whatever. As an essayist, a memoirist, I’ve never been that kind of a writer. Hell, I’m not that kind of person. I’m not interested in making others look bad, or using my craft for “revenge.” I write about what I already love. I write about what I already feel a measure of compassion for.

As for the humor – I think we often consider the application of humor to difficult subject matter as somehow trivializing the significance of the subject, or making light of experiences that are dead serious. This isn’t true. Humor is not necessarily a form of laughing at or mocking what should be respected. I think humor is an element of honesty. Even really serious shit – like cancer – isn’t without irony or hilarity. And for me, nothing about my own experience is so sacred that I can’t laugh at it. Certain lived experiences are just as fucking funny as they are awful. Humor and suffering, in my estimation, are in no way mutually exclusive. Furthermore, I think that in order to be honest, we also have to acknowledge and embrace that humor is a part of the most fucked up events and experiences we live through. I mean, we don’t want to think that there’s anything funny about a breakup, or a cancer diagnosis, but if we’re looking at those experiences carefully, if we’re distancing ourselves a bit from our ego, we have to admit there is humor there.

For me, humor has always been a way of surviving, of staying sane.

• You tackle some very challenging personal conflicts in these essays: mental health, sexuality, permanent loss, and especially a frightening medical diagnosis (I don’t want to give too much away). Can you talk a little about your personal brand of humor? How did humor, in particular, become such an integral part of your narrative voice? Can you talk a little about the difficulties you may have had to face in the process of putting these experiences to the public page?

In my storytelling, I’ve always employed humor. I like the reaction it elicits from the listener – laughter is visceral, you can feel it. Some of the earlier essays in the collection I wrote for live readings in Chicago, when I was living there, and I got a bit addicted to making people laugh because it’s instant affirmation. Plus, in my actual life, I see irony, absurdity in damn near everything – it’s just the way I think, so it feels natural to infuse humor into my essays, even the ones that concern themselves with topics/issues that are not explicitly funny. I read something once that asserted the personal essay is less about relaying an experience, and more about allowing the reader into the writer’s “habit of mind,” and the ability to see humor in the ugly, or frightening is simply my own habit of mind.

To the second part of your question, I think the greatest challenge in putting some of these experiences to “public page,” was, of course, the knowledge that I was really opening myself up, making myself vulnerable. By writing what I’ve written, complete strangers now know some pretty intimate details from my life – and sometimes that feels weird. It makes a person feel a little naked, but I also understand that to a certain degree, the person that’s being laid bare in these essays is also a persona. In my day-to-day life, I’m quieter, more introverted, more private than I am on the page.

I know some people are shocked by my candor, my honesty. Sometimes I’m shocked by my own candor and honesty, but what the fuck is the point of writing if you’re not going to be honest, if you’re not going to attempt to get at truth – “truth is beauty, beauty truth” and all that. If you’re going to write about life, actual life, you have to chronicle the mess, the indelicate shit. Good writing, good art, I think is not about being safe or being coy. It’s like the difference between Norah Jones’ music and, I don’t know, the music of Yoko Ono. If you want to listen to some really tepid, lukewarm “safe” music, then listen to Norah Jones. If you want to listen to something raw and real and fucking weird, listen to Yoko Ono. The tepid is the lie, and leaves the listener feeling numb. Even if you’re annoyed listening to Yoko Ono’s banshee wails, you’re feeling something; you’re reacting. You’re not numb.

• Passage of time in this collection is as eccentric as the people and memories you reflect upon, how does the real and/or perceived passage of time influence your daily writing? In what ways do you translate the flux and flow of memory into a cohesive account of your experience? In your opinion, what is most dangerous about memory?

Memory is so damn unreliable. To remember something, and recount that memory is to alter it forever. I’ve found that if I want to write about my own experiences, and to do that well, then I need to accept that what I’m recounting is things as they seemed rather than things as they were. Naturally, I’m concerned with accuracy, but I’m not writing a history textbook. I’m not writing an autobiography, or David Copperfield for that matter. I’m interested in telling stories. I’m interested in how seemingly disparate anecdotes relate to one another. The way those memories tie together depends on the idea I’m trying to explore. So, for example, in one of the essays from You’re Not Edith, I wanted to write about how we fathom death – this was the skeleton that I layered with memories from my experience as a cancer patient and memories of the death of a high school classmate. I seldom write chronologically; and our memories, even when they’re pretty accurate, don’t occur to us chronologically, anyway – they’re all over the place.

We like to believe that when we remember something, we’re remembering it with keen accuracy, but that’s simply not true. There isn’t just one truth. (Life would be a hell of a lot easier if there was.) Memory is slippery and subjective. So again, I feel like creative non-fiction, writing about the self, is not about chronicling a history, but about using our subjective recollection of events to illuminate some larger truth, that is only one version of one rather subjective truth.

• Finally, a question I like to ask everyone: What does the phrase “experimental literature” mean to you? Can it be adequately defined? Would you qualify your current work as experimental?

To me, experimental literature is most often manifest in hybrid forms – the prose poem, the palimpsest, the fractured narrative. I think of Italo Calvino, Gertrude Stein, Lyn Hejinian, Beckett. I don’t know that my style would fall into the experimental category. The narratives in my essays are usually pretty straightforward. I do write in fractures, I do toggle back and forth in time, but I don’t think that’s necessarily experimental. I’m not really fucking with form the way writers who I’d consider experimental do.

I do think the definition of “experimental literature,” if there is one, is fluid; it changes over time. I mean, as soon as writers en masse begin to emulate a kind of “experimental form” the form itself stops being experimental, right? In a sense, all types of writing were at some point experimental. Even the novel was, once upon a time, experimental.

Insistence on Making Something New: Brian Evenson on Experimental & Innovative Literature

To read two pieces of flash fiction by Brian Evenson, see Timber Volume 5.

1) What are your thoughts on the label “experimental” with respect to literature, in a general sense? What does the phrase “experimentalliterature” even mean to you? Can it be adequately defined?

I don’t think it can be adequately defined. At times I’ve used the term in relation to my own work, but I did that a lot more a decade ago. Know I’m more likely to use the term “Innovative” if I use a term at all–even that’s started to seem problematic to me, particularly considering the directions my work is taking. The problem with a term like “Experimental” is that it gets used quite variously at different literary moments, and that what seems experimental at one moment just doesn’t later on. If you are repeating the same gesture that another writer was doing 20 years ago, you’re no longer experimental.

2) Do you find “experimental” useful as a category? If useful, is it more useful for writers, publishers, teachers, or readers (or equally useful across the board)?

I think it’s useful as a modifier to a category, as in “Experimental Literature of the Sixties” or “Early 21st century Experimental Fiction,” or “Experimental Realism”. But just calling something “Experimental Literature” is always a little vague. It does have a certain weight behind it, in the sense that it suggests taking chances–the experiment might go wrong or fail–and does suggest an attitude toward the larger literary tradition (striking out in another direction from it), but yes, I really do think it’s most useful when it’s part of a definition rather than a definition in and of itself.

3) Whatever “experimental” might mean, in the very least it’s probably safe to say that it attempts to describe a particular subset of writers who try to distinguish themselves from “popular” literature. But: is there also a mainstream sense of experimentalism with respect to literature, distinct from other forms of experimental literature? What does it mean to be a “trendy experimental” writer/artist?

Well, I’d argue with this just a little, since I think a certain trend in the writing you’re talking about is very much their ability to incorporate popular and populist elements into their literature. A lot of writers I admire are doing work on the edge of genre and literature, trying to take advantage of both, trying to see what will happen with that sometimes odd cross-pollenization, and that strikes me as a very worth sort of experiment. I’d be reluctant to equate experimentalism with being unpopular or even obscure. On the other hand, I think that large presses sometimes praise as experimental work that simply isn’t, that ends up synthesizing in fairly obvious ways the experiments and risk-taking of other writers into something that’s not at all risky.

4) It seems to us that, when it is deployed, the term “experimental” changes depending on who is doing the experiment. Would you agree with that? If you disagree, is there a better way to understand the function of experimental literature? Or, if you do agree, in what ways does the “experiment” change based on the subject position of its author?

Yes, very much agree. I think it changes based on what else is going on in literature at a particular moment, and yes, to a degree, on the author’s subject position. I kind of feel like as soon as the experiment becomes a codified, recognizable gesture or has the clear markings of forming a genre, the experiment is over. I do think, too, sometimes, that experiments get repeated, that some of my younger students see things as experimental that I don’t, partly because I’ve seen them done before. But I’ve come as well to feel that as the cultural context changes, as things shift, maybe there is in fact a significant difference to doing a particular thing now, at this given historical moment, than there was in doing it, say, twenty years ago.

5) Is there (or maybe, should there be) a significant difference between “innovative” and “experimental” with respect to labeling? If so, can you describe that difference?

For me there is in that I think that “innovative” hasn’t been quite as co-opted as a term as “experimental.” That latter term feels a little dated to me, and there’s always something odd about taking a word from another speech genre (science) and moving it into a writing milieu. I like “innovative” better, since it has a kind of insistence on making something new, or changing it. But that’s not quite a perfect term either, particularly since both “novel” and “novella” and (in journalism) “the news” all have that same connection to the new. Though it’s a term that works for me until we dig up a better one…

Interview With Alan Ziegler by Loie Merritt

Alan, thank you for taking the time to have a conversation with me regarding your work. I’d like to focus on your flash fictions as this is what I am most fascinated by and what seems to tug on your heart strings as well, so let’s jump right in here:

• As I mentioned, your work really relishes the format of flash fiction, a sort of hotly debated sub-genre that has been around for a very long time. It seems only recently has it begun to gain some serious traction in the realm of experimental literature. What drew you to this kind of prose structure? Have you always been a devoted practitioner? Do you ever doubt its definition or power?

I doubt any firm definition of flash fiction, but never its power. I relished prose poetry before flash fiction entered the lexicon, and find that many pieces (of my own and others) could parade under either banner (the main distinction being that a piece of flash fiction promises a narrative element, whereas narrative is optional for a prose poem ). Of all the terms for short short stories, flash fiction is my favorite; the word flash implies that something is happening in the story other than brevity. To leap for a metaphor: In dog shows, miniature dachshunds compete against standards, because a miniature is just a bred-down dachshund: same creature but smaller. But Toy Fox Terriers do not compete with Smooth Fox Terriers (even though they are descended from them) because other breeds have been interjected into the mix. So, one can think of flash fiction as a bred-down short story with prose poetry injected into the mix.

• In SHORT: An International Anthology of Five Centuries of Short-Short Stories, Prose Poems, Brief Essays, & Other Short Prose Forms (Persea Books 2014), you collect a shockingly massive amount of work, all under 1250 words. What made you want to anthologize these pieces now? What challenges did the process pose? How did your own work influence or come to be influenced by the anthology?

I was aware of no anthology of short prose that crossed genres, languages, and centuries—which I’d been doing since 1989 in the packets I compiled for my Short Prose Forms classes at Columbia. I started sifting through the gobs of packets and putting together a proposal. My agent, Eleanor Jackson, was tenacious in finding the right publisher, and she hooked me up with Persea, whose books I have long admired. The first challenge was where to draw various lines so the book wouldn’t reach doorstop proportions. At first I decided to start with writers born after 1800 (Aloysius Bertrand, Poe, Baudelaire, etc.) but I kept getting drawn to earlier pieces (such as the fragments of Joubert and Chamfort), so I added a Precursors section. There I drew the line with Girolamo Cardano (born in 1501). Then I had to deal with geography. As much as I wanted to include such pieces as Kawabata’s Palm of the Hand Stories, the whole world is too big for this book, so I limited it to Western Literature. Which brings up what I called the U.S. Problem. The closer we get to present day, the fewer translations are available, and the more short prose from the U.S. is out there. I let the anthology become decidedly less international post-1950 or so. And finally, word count. I actually did this somewhat methodically. I piled up all the finalist selections and looked at what would have to be discarded at various cut-off points. 1250 resulted in the elimination of the fewest must-have pieces. My editor, Karen Braziller, and a few former graduate students (notably Annie DeWitt, Alisha Kaplan, Scott Dievendorf, Rebecca Taylor, and Alyssa Barrett) helped a lot in final selections. All of this was difficult but pleasurable work because I was in control. Then the fun stopped with the permissions process. Fortunately, I engaged the amazing Fred Courtright (aka permdude) of The Permissions Company to navigate the labyrinth. We had to obtain U.S., Canadian, and UK rights, both print and electronic; and, for translated pieces we also had to obtain the underlying rights. It took a long time, with lots of angst (and far more money than was originally budgeted).

As for influence: I was drawn to pieces that I wanted to possess in some way and be able to share with others. I feel a sense resembling authorship with many texts in the book: someone recently told me how much she treasures one of the pieces, and I almost said, “Thank you!” As I got deeper into the selection process I went beyond my accumulated packets, looking more with editorial rather than authorial eyes, seeking pieces outside of my personal sphere. Once, while teaching such a piece, a student asked, “Why do you like this piece so much?” and I responded, “Why do you assume I like it? But I do admire it.”

• Recently, I taught an exercise in poetry in which my student’s had to write “Twitter Poems” and post them to a live Twitter account. It was relatively successful, although I may have learned more than my students. As an educator and an artist, what might the short, short form achieve in today’s “say it in 140 characters or don’t bother” culture? Are there aspects of the art of writing that we miss in such a brief form?

When I started working on my college newspaper (in the era of hot type), I loved writing headlines, which were constrained by the number of characters that could fit within the editors’ layout and type size—far more constricted than Twitter. In 1974, Bill Zavatsky edited an issue of Roy Rogers magazine devoted exclusively to one-line poems. When Bill put out the word that he was looking for one-liners, I went at it (as did many of my friends) and had a ball doing so. I also write song lyrics, where the canvas is small and the stakes are high for every syllable. So, I’ve always had an affinity for pieces where function is squeezed into form. I have a handout for my Short Prose Forms class called “Tweets Before Twitter,” comprising pieces of 140 characters or less written long before there was a name for them. Brava for your writing assignment—you took them from conception to publication! If you restrict yourself exclusively to extreme brevity, you’ll miss out on the joys of meandering and lingering (among others) with story and language. But that doesn’t diminish the value of gestures—trying to convey in a few words what a great actor can do with a tilt of an eyebrow and a wave of the hand.

• In your own work, you somehow manage to capture an impressive voluptuousness of life, fused with a very dry wit in nearly every piece. Does this kind of brevity come natural to you? Can you tell me just a bit about your process; how do you enact the necessary reduction of words to sweeten (or sour), and concentrate your language?

I have learned not to “leave well enough alone”: after I think I have gone as far as I can with fine-tuning a piece, I know that in a couple of hours or days (or longer) I will see more opportunities. It’s not just about cutting—it’s also about recognizing opportunities to take something a step or a leap further. I am most comfortable when I can see the whole piece in front of me, when I can disassemble and reassemble repeatedly.

• Your work seems to consistently struggle, or play with, the passage of time, exposing an artistic evolution, a sort of maturation of words as much as character. Why does time in particular seem to resonate with you? Why is it important that these emotional and temporal layers are woven into such short pieces?

One of my longer stories (a whopping 1600 words), “The Green Grass of Flatbush,” includes the following dialogue: “There’s never enough time,” my mother says. “No, mom, time is the only thing we have as much of as we can use. It is the only thing that is always with us.” And later, the narrator says, “Yes,” I reply, “bad timing. We can’t control time, but we should try to do something about timing.” I suppose my playful struggle (to combine your terms) is to control the perception of time through the timing of the language. Kurt Vonnegut generously wrote, “The timing and the surprising implications of his endings in particular mark him as a fully mature artist.” I was so gratified to hear that because knowing when and how to end is as important as knowing when and how to begin. What happens in between is that playful struggle. I’m glad you mention the maturation of words. When I think of time in my writing, I think musically, the way a piece of music develops and resolves. Even if there is not a high degree of closure, a piece of writing (and music) must end rather than just stop. It must mature in some satisfying way.

• And humor is crucial too. Does it ever perform as a shield for you? I suppose what I’m wondering is does the application of wit or sarcasm better express complex ideas (issues of relationships, aging, or disappointment) by making them more digestible?

Yes, humor can make complex ideas more digestible—and tastier—so it’s a natural connection. It’s important that humor not act predominantly as a shield (though shields do go—literally—hand in hand with swords). When I was in graduate school I studied with Joel Oppenheimer. I was prone to go for the laugh rather than risk sentimentality, and Joel told me he was trying to “separate the tummler from the poet” in me. (A tummler is an entertainer whose main mission is to keep everyone laughing, from the Yiddish “to make a racket.”) The challenge is to combine the tummler and the poet—to use humor in the service of the work rather than as an end in itself. Humor comes naturally to me, especially when it involves wordplay: In a notebook I kept during a family trip when I was 12, I wrote: “We got up early this morning and hit the road. When our hands got tired we got into the car and drove off.” It made me laugh then, and it makes me laugh now that it made me laugh then.

• Do any characters or voices recur in your work? Is each piece a new narrative? Do they ever blend or slide into one another?

I’m currently—and have been for a long time—working on a “memoir in flashes” (tentatively titled Based on a True Life), so the narrator (me) stays the same, many characters recur, and the voices—though they change with age—do “blend or slide into one another.” This provides me with the comfort of connectivity that doesn’t usually occur when I write short pieces: I know who is talking before I begin. Of course, this has its limitations, and I couldn’t imagine not being able to invent when I write. Most of these kinds of pieces start with language—a phrase, an image—and I am often surprised by where I lead myself.

• Finally, I’m curious if you think all flash fiction can qualify as an experimental form? Are there certain approaches that live in a more traditional or canonical realm? What makes this form and your delightful work in it so popular and valuable today?

Lauro Zavala (a Mexican scholar who is doing amazing work in the field of short prose) told me that in Spanish “Minificción refers to a new literary genre that mixes literary and extra-literary traditions, whereas Microrrelato means simply a very short narration.” Perhaps we can make a similar distinction between flash fiction and short short story. Terminology fascinates me, especially when terms expand rather than constrict a writer’s options; flash fiction is, for me, an essential option, thus making it hugely valuable. But we shouldn’t get bogged down in terminology. In 1976, Russell Edson wrote me: “And what’s so wonderful, we don’t know what we’re doing, we’re just doing…” I love that he ended the note with ellipses…

Thank you again for your time and consideration with this heavy, remarkably wordy, series of questions!

And thank you. Your series of questions make for wonderful reading on their own!